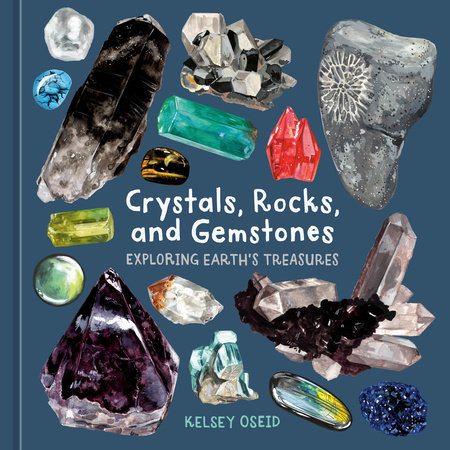

A beautifully illustrated, entertaining, and educational guide to the world’s crystals, rocks, gemstones, and other geological phenomena from the acclaimed author of What We See in the Stars.

Rocks and minerals have captivated the human imagination for centuries. Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones explores the most interesting and illuminating facts about these precious treasures, from how rocks form and why gems come in different colors, to what makes a diamond valuable and why people feel a spiritual connection with crystals. Did you know that fossils made entirely out of iridescent opal have been found? Or that the ancient Egyptians believed that adorning mummies with emeralds ensured safe passage to the afterlife?

With gorgeous illustrations on every page, this covetable guide delves into the natural history, uses, and cultural significance of over 80 stones, their place in our history, and our fascination with these gifts of the earth. Perfect for lovers of nature, rock collectors, and crystal afficionados, Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones will delight and inspire readers of all ages.

Rocks and minerals have captivated the human imagination for centuries. Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones explores the most interesting and illuminating facts about these precious treasures, from how rocks form and why gems come in different colors, to what makes a diamond valuable and why people feel a spiritual connection with crystals. Did you know that fossils made entirely out of iridescent opal have been found? Or that the ancient Egyptians believed that adorning mummies with emeralds ensured safe passage to the afterlife?

With gorgeous illustrations on every page, this covetable guide delves into the natural history, uses, and cultural significance of over 80 stones, their place in our history, and our fascination with these gifts of the earth. Perfect for lovers of nature, rock collectors, and crystal afficionados, Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones will delight and inspire readers of all ages.

Rocks, Gems, Crystals, And Minerals: An Overview

Interest in minerals goes back as far as humans have been able to find them. From lumps of turquoise and spears of quartz to sheets of glittering mica and pieces of precious corundum, there are so many minerals that can catch our eye. Even without knowing the first thing about their origins, their names, or their chemical makeups, we find crystals simply fascinating. From the most traditional geologist to the most eccentric crystal mystic, no one can deny the powerful beauty of the perfect stone.

Few natural items are as treasured by collectors as minerals, crystals, and gems. Many people have an impulse to gether, hold, and keep these chunks of matter—even though, on some level, we know we can't really "own" them at all, since most of them have been around for billions of years and will outlast us by billions more. Putting a crystal on a shelf in your home is more akin to borrowing it than truly prossessing it—except the lender, the Earth, will hardly notice the exchange.

Does the allure of a crystal really come just from its beauty? Sure, crystals are beautiful in the conventional sense. Amethyst, the purple variety of quartz, is an oft-cited favorite and is the cornerstone of many a crystal collection. It sparkles, shines, and has a lovely, gentle hue. But it isn’t just surface-level beauty that draws us to crystals, since imitation crystals—made, say, out of cut glass or polished epoxy resin—lack the same appeal and are comparatively worthless. There’s nothing rare or special about a fake plastic jewel formed by a human or a machine. It didn’t develop its crystal form through millennia of hyperintense pressure in the mantle of the Earth, or explode from the center of a volcano before cooling in seawater. There’s something that feels intrinsically powerful about a natural crystal’s journey through time. We don’t value just the look of a stone, but also its backstory—or are we talking about its life story, or its soul?

Of course, minerals are not living things. In fact, part of what defines minerals as a category is their inorganic origin. But we often can’t help but personify them, ascribing living qualities to their beauty. When precious stones like diamonds are faceted to best enhance their appearance, we say they now have “more life”; in other instances, stones have different levels of “play” in the rapidly changing sparkles and glints as the stone is turned. Sometimes stones are named after body parts—for example, Pele’s hair and Pele’s tears are two natural artifacts that can result from volcanic eruptions, and gems with glinting inclusions are called “cat’s eyes.”

While minerals don’t need us in the least—after all, humanity is barely a blip on the Earth’s geological timeline—we certainly need them. Calcium is necessary for our teeth and bones; iron is essential for our blood; and potassium, sodium, and zinc have a multitude of health benefits. Minerals, whether obtained naturally from food sources or through supplements, are part of our daily lives. And, of course, so are the mineral rocks that comprise our buildings, roads, and other physical infrastructure. Then there’s our technology—the phones, wearables, and other devices that are ever more embedded in the daily operations of our society. These devices wouldn’t function without rocks and minerals like bauxite, the provider of gallium for LED displays; cassiterite, which comprises tin circuit boards; and chalcopyrite, the source of copper used for conducting heat and electricity. We are beholden to the power of minerals to keep our daily lives intact. This, combined with the mystique of crystals, the history revealed by cut and sculpted rock formations, and the beauty of gems, makes the study of rocks, gems, and minerals an essential part of understanding not just our Earth but also ourselves.

Interest in minerals goes back as far as humans have been able to find them. From lumps of turquoise and spears of quartz to sheets of glittering mica and pieces of precious corundum, there are so many minerals that can catch our eye. Even without knowing the first thing about their origins, their names, or their chemical makeups, we find crystals simply fascinating. From the most traditional geologist to the most eccentric crystal mystic, no one can deny the powerful beauty of the perfect stone.

Few natural items are as treasured by collectors as minerals, crystals, and gems. Many people have an impulse to gether, hold, and keep these chunks of matter—even though, on some level, we know we can't really "own" them at all, since most of them have been around for billions of years and will outlast us by billions more. Putting a crystal on a shelf in your home is more akin to borrowing it than truly prossessing it—except the lender, the Earth, will hardly notice the exchange.

Does the allure of a crystal really come just from its beauty? Sure, crystals are beautiful in the conventional sense. Amethyst, the purple variety of quartz, is an oft-cited favorite and is the cornerstone of many a crystal collection. It sparkles, shines, and has a lovely, gentle hue. But it isn’t just surface-level beauty that draws us to crystals, since imitation crystals—made, say, out of cut glass or polished epoxy resin—lack the same appeal and are comparatively worthless. There’s nothing rare or special about a fake plastic jewel formed by a human or a machine. It didn’t develop its crystal form through millennia of hyperintense pressure in the mantle of the Earth, or explode from the center of a volcano before cooling in seawater. There’s something that feels intrinsically powerful about a natural crystal’s journey through time. We don’t value just the look of a stone, but also its backstory—or are we talking about its life story, or its soul?

Of course, minerals are not living things. In fact, part of what defines minerals as a category is their inorganic origin. But we often can’t help but personify them, ascribing living qualities to their beauty. When precious stones like diamonds are faceted to best enhance their appearance, we say they now have “more life”; in other instances, stones have different levels of “play” in the rapidly changing sparkles and glints as the stone is turned. Sometimes stones are named after body parts—for example, Pele’s hair and Pele’s tears are two natural artifacts that can result from volcanic eruptions, and gems with glinting inclusions are called “cat’s eyes.”

While minerals don’t need us in the least—after all, humanity is barely a blip on the Earth’s geological timeline—we certainly need them. Calcium is necessary for our teeth and bones; iron is essential for our blood; and potassium, sodium, and zinc have a multitude of health benefits. Minerals, whether obtained naturally from food sources or through supplements, are part of our daily lives. And, of course, so are the mineral rocks that comprise our buildings, roads, and other physical infrastructure. Then there’s our technology—the phones, wearables, and other devices that are ever more embedded in the daily operations of our society. These devices wouldn’t function without rocks and minerals like bauxite, the provider of gallium for LED displays; cassiterite, which comprises tin circuit boards; and chalcopyrite, the source of copper used for conducting heat and electricity. We are beholden to the power of minerals to keep our daily lives intact. This, combined with the mystique of crystals, the history revealed by cut and sculpted rock formations, and the beauty of gems, makes the study of rocks, gems, and minerals an essential part of understanding not just our Earth but also ourselves.

Copyright © 2025 by Kelsey Oseid. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Photos

About

A beautifully illustrated, entertaining, and educational guide to the world’s crystals, rocks, gemstones, and other geological phenomena from the acclaimed author of What We See in the Stars.

Rocks and minerals have captivated the human imagination for centuries. Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones explores the most interesting and illuminating facts about these precious treasures, from how rocks form and why gems come in different colors, to what makes a diamond valuable and why people feel a spiritual connection with crystals. Did you know that fossils made entirely out of iridescent opal have been found? Or that the ancient Egyptians believed that adorning mummies with emeralds ensured safe passage to the afterlife?

With gorgeous illustrations on every page, this covetable guide delves into the natural history, uses, and cultural significance of over 80 stones, their place in our history, and our fascination with these gifts of the earth. Perfect for lovers of nature, rock collectors, and crystal afficionados, Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones will delight and inspire readers of all ages.

Rocks and minerals have captivated the human imagination for centuries. Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones explores the most interesting and illuminating facts about these precious treasures, from how rocks form and why gems come in different colors, to what makes a diamond valuable and why people feel a spiritual connection with crystals. Did you know that fossils made entirely out of iridescent opal have been found? Or that the ancient Egyptians believed that adorning mummies with emeralds ensured safe passage to the afterlife?

With gorgeous illustrations on every page, this covetable guide delves into the natural history, uses, and cultural significance of over 80 stones, their place in our history, and our fascination with these gifts of the earth. Perfect for lovers of nature, rock collectors, and crystal afficionados, Crystals, Rocks, and Gemstones will delight and inspire readers of all ages.

Author

Excerpt

Rocks, Gems, Crystals, And Minerals: An Overview

Interest in minerals goes back as far as humans have been able to find them. From lumps of turquoise and spears of quartz to sheets of glittering mica and pieces of precious corundum, there are so many minerals that can catch our eye. Even without knowing the first thing about their origins, their names, or their chemical makeups, we find crystals simply fascinating. From the most traditional geologist to the most eccentric crystal mystic, no one can deny the powerful beauty of the perfect stone.

Few natural items are as treasured by collectors as minerals, crystals, and gems. Many people have an impulse to gether, hold, and keep these chunks of matter—even though, on some level, we know we can't really "own" them at all, since most of them have been around for billions of years and will outlast us by billions more. Putting a crystal on a shelf in your home is more akin to borrowing it than truly prossessing it—except the lender, the Earth, will hardly notice the exchange.

Does the allure of a crystal really come just from its beauty? Sure, crystals are beautiful in the conventional sense. Amethyst, the purple variety of quartz, is an oft-cited favorite and is the cornerstone of many a crystal collection. It sparkles, shines, and has a lovely, gentle hue. But it isn’t just surface-level beauty that draws us to crystals, since imitation crystals—made, say, out of cut glass or polished epoxy resin—lack the same appeal and are comparatively worthless. There’s nothing rare or special about a fake plastic jewel formed by a human or a machine. It didn’t develop its crystal form through millennia of hyperintense pressure in the mantle of the Earth, or explode from the center of a volcano before cooling in seawater. There’s something that feels intrinsically powerful about a natural crystal’s journey through time. We don’t value just the look of a stone, but also its backstory—or are we talking about its life story, or its soul?

Of course, minerals are not living things. In fact, part of what defines minerals as a category is their inorganic origin. But we often can’t help but personify them, ascribing living qualities to their beauty. When precious stones like diamonds are faceted to best enhance their appearance, we say they now have “more life”; in other instances, stones have different levels of “play” in the rapidly changing sparkles and glints as the stone is turned. Sometimes stones are named after body parts—for example, Pele’s hair and Pele’s tears are two natural artifacts that can result from volcanic eruptions, and gems with glinting inclusions are called “cat’s eyes.”

While minerals don’t need us in the least—after all, humanity is barely a blip on the Earth’s geological timeline—we certainly need them. Calcium is necessary for our teeth and bones; iron is essential for our blood; and potassium, sodium, and zinc have a multitude of health benefits. Minerals, whether obtained naturally from food sources or through supplements, are part of our daily lives. And, of course, so are the mineral rocks that comprise our buildings, roads, and other physical infrastructure. Then there’s our technology—the phones, wearables, and other devices that are ever more embedded in the daily operations of our society. These devices wouldn’t function without rocks and minerals like bauxite, the provider of gallium for LED displays; cassiterite, which comprises tin circuit boards; and chalcopyrite, the source of copper used for conducting heat and electricity. We are beholden to the power of minerals to keep our daily lives intact. This, combined with the mystique of crystals, the history revealed by cut and sculpted rock formations, and the beauty of gems, makes the study of rocks, gems, and minerals an essential part of understanding not just our Earth but also ourselves.

Interest in minerals goes back as far as humans have been able to find them. From lumps of turquoise and spears of quartz to sheets of glittering mica and pieces of precious corundum, there are so many minerals that can catch our eye. Even without knowing the first thing about their origins, their names, or their chemical makeups, we find crystals simply fascinating. From the most traditional geologist to the most eccentric crystal mystic, no one can deny the powerful beauty of the perfect stone.

Few natural items are as treasured by collectors as minerals, crystals, and gems. Many people have an impulse to gether, hold, and keep these chunks of matter—even though, on some level, we know we can't really "own" them at all, since most of them have been around for billions of years and will outlast us by billions more. Putting a crystal on a shelf in your home is more akin to borrowing it than truly prossessing it—except the lender, the Earth, will hardly notice the exchange.

Does the allure of a crystal really come just from its beauty? Sure, crystals are beautiful in the conventional sense. Amethyst, the purple variety of quartz, is an oft-cited favorite and is the cornerstone of many a crystal collection. It sparkles, shines, and has a lovely, gentle hue. But it isn’t just surface-level beauty that draws us to crystals, since imitation crystals—made, say, out of cut glass or polished epoxy resin—lack the same appeal and are comparatively worthless. There’s nothing rare or special about a fake plastic jewel formed by a human or a machine. It didn’t develop its crystal form through millennia of hyperintense pressure in the mantle of the Earth, or explode from the center of a volcano before cooling in seawater. There’s something that feels intrinsically powerful about a natural crystal’s journey through time. We don’t value just the look of a stone, but also its backstory—or are we talking about its life story, or its soul?

Of course, minerals are not living things. In fact, part of what defines minerals as a category is their inorganic origin. But we often can’t help but personify them, ascribing living qualities to their beauty. When precious stones like diamonds are faceted to best enhance their appearance, we say they now have “more life”; in other instances, stones have different levels of “play” in the rapidly changing sparkles and glints as the stone is turned. Sometimes stones are named after body parts—for example, Pele’s hair and Pele’s tears are two natural artifacts that can result from volcanic eruptions, and gems with glinting inclusions are called “cat’s eyes.”

While minerals don’t need us in the least—after all, humanity is barely a blip on the Earth’s geological timeline—we certainly need them. Calcium is necessary for our teeth and bones; iron is essential for our blood; and potassium, sodium, and zinc have a multitude of health benefits. Minerals, whether obtained naturally from food sources or through supplements, are part of our daily lives. And, of course, so are the mineral rocks that comprise our buildings, roads, and other physical infrastructure. Then there’s our technology—the phones, wearables, and other devices that are ever more embedded in the daily operations of our society. These devices wouldn’t function without rocks and minerals like bauxite, the provider of gallium for LED displays; cassiterite, which comprises tin circuit boards; and chalcopyrite, the source of copper used for conducting heat and electricity. We are beholden to the power of minerals to keep our daily lives intact. This, combined with the mystique of crystals, the history revealed by cut and sculpted rock formations, and the beauty of gems, makes the study of rocks, gems, and minerals an essential part of understanding not just our Earth but also ourselves.

Copyright © 2025 by Kelsey Oseid. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Back to Top

Notifications