“Come on, the sun is up! Let’s go outside after breakfast!” I exclaimed to my next-door neighbor Shannon as the cord of the house phone curled around my little hands. I smashed down the phone and rushed to get ready, looking in the mirror to pat down my afro before going to see what my parents were cooking.

My dad stood in the kitchen in his slippers and socks, sweatpants, and a rolled-up windbreaker over a cut-off T-shirt, surrounded by the scent of oatmeal. “Come eat!” he said in his thick Jamaican accent. Growing up, I loved when my dad made my oatmeal for me—always with brown sugar and berries. I would stand by his side as he cooked, and persuade him to add more sugar. People often have cornmealor oatmeal-based porridge for breakfast in Jamaica, and that joyful morning ritual was one of the many ways my parents effortlessly integrated our family heritage into my childhood.

I was five when I realized that I wanted to spend my days exploring nature. From sunrise to sunset, no one could find me. Shannon, who loved being outdoors as much as I did, would be waiting for me before I finished my last spoonful of oatmeal. After breakfast, we would embark on one of our adventures, spending the day in the untrodden woods of Cheshire, Connecticut, admiring and connecting with nature. These innocent mornings were filled with the scent of pine trees, skunk cabbages, and morning dew.

It was during these magical days that I discovered my first forageable foods. “Look, Mom!” I cried out breathlessly. “Wild garlic! It smells so good! Can I eat it? I’m pretty sure it’s garlic. It smells like garlic. It looks like garlic!” Every spring I feel the very same thrill of discovery, as though it’s my first day exploring the woods. I remember the taste of juicy wineberries, a deliciously sweet variety of raspberry that grew at the edge of the woods by my childhood home. They were my absolute favorite. I can still feel the thorns pricking my little fingers while I searched for the juiciest, most plump berries. I ate them until my heart was content.

At the end of every summer, when wild grapes grew in, I forced myself to taste the fruit, which made my mouth pucker with each bite. Even though they were sour, just knowing that they were edible was reason enough for me to try them. The undeniable curiosity to explore, find, and eat wild foods has stayed with me all my life, and what began as playful childhood adventures evolved into a lifelong passion for foraged cooking. The reward of taking a mushroom home for flavor and sustenance still overwhelms my brain with a satisfying rush of dopamine.

Foraging is a deeply sensory activity. It often begins with seeing a plant or mushroom, followed by smelling, touching, and, finally, tasting it. When you find something new, you bring it home, observe it, and, once you have positively identified it, eat it. I think that is why I have such a deep love and respect for foraging. You become one with the ingredient before you even taste it, and you gain a closer relationship with your food. I had one of my first experiences with cooking when I was about twelve years old. Our new next-door neighbors, a couple from Argentina, had a daughter, Denise, who was about my age, and we quickly became friends. I loved watching her mother, Sabrina, cook effortlessly while the Spanish pop ballad “Soy Rebelde,” by Jeannette, played in the background. One day, I asked if I could cook with her. We made fresh cracked–black pepper pasta, carrot cake (my favorite), and empanadas. Sabrina always encouraged and nurtured my exploratory spirit, and because of her lessons, I quickly decided that the kitchen was a space I wanted to be in forever.

In high school, I took a business class in which I created a proposal for a dream venture centered around making vegetarian and vegan food accessible, affordable, and delicious. My parents had raised their seven kids on a vegetarian diet when plant-based food was nowhere near as widely available as it is today. I wanted to fix the problems that I faced as the girl who always had to get fries and a salad because there were no other vegetarian options. I brought that business plan to life in my second year of college, when I started my own catering company, Chrissy’s. While working a full-time tech job, I committed to keeping my food career foremost in my mind. The one person who always believed in and encouraged me was my dad. He worked hard to realize every dream he ever had and, together with my mother, nurtured that same work ethic in me. They accomplished everything they wanted to do in life, despite starting with very little, and they inspire me daily.

In 2019, I embarked on my first professional restaurant experience in New Haven, Connecticut—the pizza capital of the world. Thanks to the success of my catering business, I was hired at a well-known pizza joint, Da Legna at Nolo. I was in charge of managing the large, imported wood-fired pizza ovens, and, as the only woman working in the kitchen, I was known as “the pizza girl.” I always found ways to “veganize” the classic pies, and the highlight of my job was my Meatless Monday program. On those days, in addition to making a line of vegan pizzas with inspired cheese alternatives, I was able to introduce the community to inventive plant-based main plates and desserts. The concept quickly took off, and omnivores would line up, much to my surprise, asking when the next event was. That’s the moment I realized I was on to something big and took the leap to center my entire life around cooking. I expanded my catering business, and, soon after, quit my day job. Chrissy’s was a success. And yet it felt like something was missing. I found myself seeking the adventurous, childlike spirit that first connected me with food. I wanted to explore and incorporate wild, unique vegetables in ways that would surprise and delight my clients. I knew I needed to get back into nature.

My return to the wild began in 2019 with regular hikes and finding new sites that brought me joy. On one expedition in Wolcott, Connecticut, where I enjoyed walking, I had a revelation. I slowed down and stopped chasing the views at the top, taking time to smell the spruce pines. I walked through old forest, admiring the beauty of the wild trillium flowers that grew by the lake. At the edge of the water, I stumbled upon a patch of wild garlic, which I loved so much as a child. I picked a chive, and pure joy came flooding back as I nibbled on it. It is and always has been the wild garlic that inspires me. At that moment, I knew what I had to do: It was time for me to explore the unknown and master uncharted territories.

Foraging is the closest thing I’ve found to treasure hunting, and personally, the treasures I find in the woods are more precious than gold. My relationship to foraging intensified and reignited my passion for learning. The practice provides a lot of space for growth, discovery, and innovation. For me, it feels ancestrally connective, deeply rooted in stories and experiences I have never known but are within me. I shouldn’t have been so surprised by my fascination with wild ingredients. As a first-generation Jamaican American, foraging is in my blood. I was sixteen years old the first time I went to Jamaica. I remember it being a big deal for my parents, who came to the United States to live the American dream. It was a moment where their eyes said “we made it” without them saying anything at all. They couldn’t wait for the day where our family of nine ventured to their homeland and experienced a bit of what life was like through their eyes. Upon our arrival, Grandma Hazel, eager to share a meal with us, went straight outside to harvest native fruits and veggies that grew wild in her backyard. I was immediately captivated by the way she lived—a lifestyle once necessary for the original inhabitants of the country.

In the 1800s, the Maroon people, a group of Africans who escaped slavery, hid away in the mountainous regions of Jamaica. They survived, in part, by foraging from the abundant edible wild plants on the ancient Caribbean island, including plantains, maize, yams, and a variety of root vegetables. They also hunted wild animals. Most of the communities formed in inaccessible areas—unpopulated, yet dense with vegetation. To this day, foraging and preserving native plants are important tools for combating food insecurity. Jamaica might be an impoverished country, but it is rich in biodiversity.

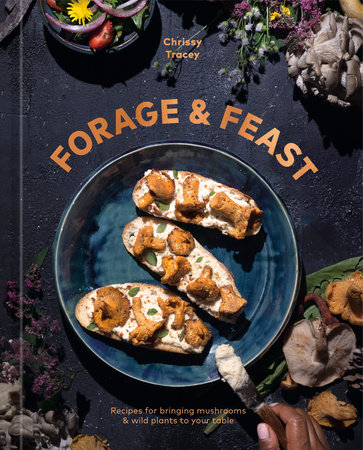

Foraging has come to mean so much more to me since I realized how connected it is to my Jamaican heritage. Little did I know when I first started exploring the woods that it would become a major inspiration for my culinary career. Professionally I’m a vegan chef, but I often think of myself as more than that: I’m a forager and an innovator. I am constantly attempting to find new ways of making plant-based foods fun, exciting, and accessible. I often incorporate foraged foods into the work I do today, whether I’m catering, cooking as a private chef or at a special event, or entertaining friends.

Copyright © 2024 by Chrissy Tracey. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.