IntroductionA-Gong, my paternal grandpa, was an architect. After my mom had my brother and me, he built a wooden house for us to grow up in. The house nestled at the foot of a mountain near Tamsui River, on the outskirts of Taipei, where trees were black in the night and our whispers hid behind deciduous leaves. With most of Taipei facing the seismic shifts that came with modernization, Tamsui seemed frozen in time, free from the noises of the city. Something very raw and real remained at that little township we called home.

Many nights, A-Gong sat at his slanted drafting desk in the living room. The room would be completely dark, save for the skirt of light on a single incandescent lamp. He was always drawing something or building something. When he noticed me looking, he invited me to watch him work. I propped myself on a wooden stool next to him, close enough to pick up a faint odor of sweat and sawdust. He aligned his fountain pen to a steel ruler under the light, its luminous halo and the shadows extending from his thick calloused fingers warped with each decisive stroke. He was like a conductor when he drew. In the silence of the room, the smooth zips from his pen tip took turns with the symphony of frogs and cicadas outside. The arch on his right rear shoulder moved up and down.

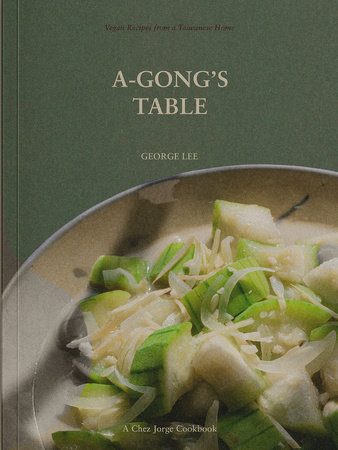

A-Gong didn’t grow up with a lot, so he wanted to give us everything. He hand-sawed every wooden tile in the flooring of our house and polished every inflection on the walls. He put together everything from desks and closets to child-size cars and rocking chairs for us to play with. He spent years building, plowing, and tilling the backyard to make a mini farm and grow fresh fruits and vegetables for us to eat. At the height of summer, papayas grew so full and sweet, they snapped the branches and fell to our feet. Sweet potatoes’ cordate leaves poked through the soil, and heads of green cabbage bloomed like roses. Meals took place at the round table he built and consisted mostly of what he grew, simply cooked and seasoned to accentuate their natural flavors.

Ten-year-old me wouldn’t be telling you about how great A-Gong and this all was. I was afraid of him. Often, I hated him. He coughed up dense phlegm from forty years of smoking and strode with fingers interlocked behind his back like a mob boss. He hardly ever smiled, let alone cried or uttered any affirmations of love. His expectations of everyone in the household were so high and insurmountable that you were better off keeping quiet around him, lest you say something that made him frown.

I would, instead, be telling you about the times we shared at the dining table. He didn’t bring his sternness there. He was too busy gnawing on pork ribs, vacuuming rice with pendulum-like chopstick swipes, and taking sips of broth. He was particular about the way each dish should look and taste. He would throw a tantrum if the fish he liked to eat wasn’t the correct size; but if it were, he became so chirpy, you could talk him into agreeing with pretty much anything. He spoke endlessly about which street vendor sold the best sugar-fried chestnuts and the nuances in a bowl of sesame oil chicken soup. Listening to him made me want to experience everything as he did, to imprint his flavors on my palate completely. I studied his gesture as he dusted sweet potato fries so liberally in plum powder that they almost turned pink. I added hefty dashes of white pepper the same way he did to rice noodle soup. Steam carried the pepper into our nostrils and made us sneeze. We laughed until our eyes watered and slurped the noodles like it was our first.

I was seventeen when A-Gong died. It was raining outside that morning. Or maybe it wasn’t. Something else diluted the colors of the spring breeze. He lay on a bed in the middle of the living room under a white blanket. A group of Buddhist nuns in gray robes circled him, each with their eyes closed and palms clasped. They hummed the Buddha’s mantra to the tempo of a handbell. The body’s separation from the soul takes eight hours, they said. It is an enormously painful process, like a thousand needles. They chanted to soothe his pain. I observed as strands of smoke from their incense sticks strung together above us into one threadbare gauze. It grew larger and larger, rose higher and higher, then disappeared. Don’t cry near him, they said, for he can still hear us.

That night, the kitchen was noticeably quieter. The clatter of pots and ladles was no more. Our family had dinner at the round table and saved his seat, the one under the window. We sat and ate together and there was no conversation, no sound but the tinkling of cutlery. My chest suddenly sank into a kind of emptiness. I wondered if dinner was ever going to feel normal again. I wondered if a new normal would mean we forgot about A-Gong. Were those once familiar feelings, smells, and tastes about to dim as our memories do?

My parents and I started going to the monastery where the nuns lived, Taipei’s Dizang Temple. I had no idea what to expect there. I wasn’t Buddhist myself, neither was A-Gong, nor was my family. To us, Buddhism likens to the rhythms of the Earth. We don’t necessarily subscribe to it or notice it. It’s always there, steeped into the background noises, occasionally surfacing to give us the guidance we need. We met Huìshàn shifu, a senior nun, at the monastery. We followed her in single file through an aisle that led from the front prayer room to the back kitchen. The aisle is long and narrow enough that you couldn’t see the other end, where it led to. Turning her head slightly, shifu told us that the soul of the deceased stayed around for forty-nine days. It is at least for that time we, the immediate family, practice Buddhist precepts and accumulate gongdé (功德), “virtue from kindness.” The most important part was to refuse meat. Consuming meat meant consciously harming innocent lives, and doing so set back the chances of a good reincarnation for A-Gong.

Unlike the entrance, a red arch that enshrined golden Buddhist swastikas, the only roof over the back kitchen is a corrugated iron sheet. The nuns cooked for us there, all forty-nine days. I remember the first vegetarian bento box they made. I remember its warmth in my cold palm when I rolled off the rubber band. In the largest section of the box, a heap each of fried tofu skin rolls and lion’s mane mushrooms squished together over a bed of steamed rice. The smaller dividers were filled with stir-fried greens, steamed kabocha, and roasted nuts. I balanced a mushroom floret between my chopsticks and took a small bite. Juices weeped from it.

The nuns had their way of making elegant yet unpretentious food that people might enjoy even in grieving and ascetic training. They made us sushi rolls that were as long and heavy as burritos, stuffed with vegetarian meat floss and vegetarian ham, minced bean curd, and strips of crunchy burdock root, cucumbers, and carrots. Aged mustard greens stir-fried with wheels of fried gluten that fronted a most natural musk. Savory soups stewed with medicinal herbs and all kinds of beans, seeds, and fungi. You could taste the care in each dish and each component. They grew the vegetables themselves and made the soy milk, tofu, and vegetarian meat products by hand. My dad, who usually appreciated a heavy plate of steak, took lion bites of the sushi burritos and confessed, “We should eat like this more often.”

At sundown, the nuns brought food offerings to our home altar. They were meals for our departed A-Gong, and most were vegetarian meats. There were konjak mock shrimps in colorful cups lined with romaine lettuce. They had pinkish-orange stripes just like the real thing; the transparent muscular tails looked like they could jump off the altar table when we weren’t looking. Vegetarian versions of fried Taiwanese sausages, salty fish roe, and smoked shark steaks—all A-Gong’s favorites— were sliced on a diagonal, neatly arranged on a plate, and garnished with purple orchids. Out of curiosity, I asked one of the nuns why they went out of their way to make and use these imitations. “It’s simple.” Her cheeks dimpled. “It’s so that people who aren’t used to eating vegetarian food can ease into the process!” I chuckled, thinking about how A-Gong would furrow his brows after trying a bite, finding out he’d been scammed. The first obstacle of afterlife is an eternally storming desert, said the nun. But the light from our positivity and prayers is powerful enough to cut through the winds and lead him down the right path.

We abstained from eating meat for a hundred days in total, or some more. The end of funeral traditions meant that Buddhist customs no longer required us to stay vegetarian. I ate my last vegetarian bento sitting on a bench outside of the crematory, and we escorted the ashes in an urn to the columbarium. I slowly introduced meat back into my diet, as did my parents. By that time, I had already lost the appetite for chunks of meat that required a fork and a knife. I frequented vegetarian restaurants because they offered the variety of vegetables and legumes I had grown accustomed to. I didn’t think of it consciously then, but my outlook on food had changed.

Copyright © 2024 by George Lee. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.