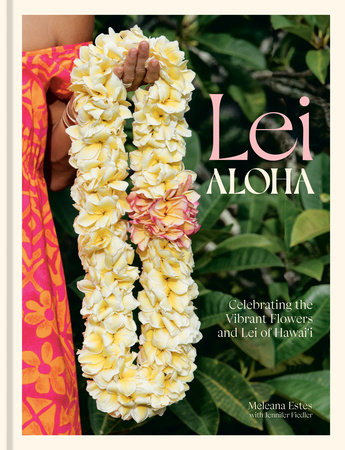

Haku Aloha

Weaving AlohaSo many of my favorite memories of growing up in Hawai‘i revolve around lei. Delicate, white feather-style ginger at a family lū‘au. Mom’s favorite fragrant lei pakalana brought home by my dad on a Friday after a long workweek. Lei palapalai (a native fern) gathered and made as we hiked along a trail in Kōke‘e. Brown paper bags, speckled with water spots holding plumeria lei made the night before for our May Day performance. Running to the ocean’s edge, laden with lei haku made of multicolored ti, to greet a canoe paddling in from the finish line at a state canoe regatta. Pua kenikeni lei hanging from Tūtū’s outstretched arms ready to hug us in her big squeeze of aloha (love) and fragrance, when we drove up to her home in Mānoa after flying to O‘ahu from Kaua‘i.

My ‘ohana’s (family’s) banana and citrus farm on the north shore of Kaua‘i was an abundant world of green. Laua‘e and palapalai fern, kukui, ‘ulu, wide swaths of white and yellow ginger, and tall coconut trees all mixed in with our carefully planted pua kenikeni and plumeria trees, essential flowering trees for our lei-making family. It was my Honolulu-based tūtū, my grandmother, Amelia Ana Ka‘ōpua Bailey, who taught her entire family to truly love all things lei and to plant lei flowers everywhere we lived as ‘ohana. A seamstress and costume designer by trade, Tūtū had an eye for color combinations, texture, and pattern. She made lei kui (sewn) her whole life. My mom remembers wearing lei poepoe (strung in a round style), made from white plumerias grown in the backyard, to school over her handmade mu‘u (short for mu‘umu‘u) on May Day. Because she learned her signature wili (wrapped) style later in life, she would begin every lei workshop she taught by saying she was “a renaissance lei maker.” She meant that she got into lei making as it was re-emerging along with many other Hawaiian arts during the 1960s. She did not learn from her kūpuna (grandparents). She was proud that her mo‘opuna (grandchildren) could say that we did.

Tūtū became captivated by traditional Hawaiian lei when my mom and dad chose to have a Hawaiian wedding, which was not common at the time. Dad and the groomsmen wore longsleeve aloha shirts; Mom wore a holokū (a style of dress with a high neck, yoke, long sleeves, and modest train). She wanted a lei po‘o (head lei) and for her bridesmaids to carry lei rather than bouquets. It was hard to find anyone making lei haku (lei braided with more than one material) in Honolulu in 1968, so Tūtū and a friend from the garden club wired white kukui blossoms together and invented one. Tūtū was hooked. After the wedding, she took apart the thick green lei from the Big Island that my mother and her bridesmaids carried to see how they were made. She started going to the Bishop Museum to find historical photos of lei. She sought out great Hawaiian lei-making masters, Barbara Meheula and Marie McDonald, and sat for hours cleaning materials for them, learning by watching.

Tūtū made all styles of lei, but her specialties were the lei kui made from the pua kenikeni she grew in her yard, climbing on her ladder to pick her blossoms well into her seventies, and her intricate lei po‘o done in the wili style. She would arrive at any party or ladies’ luncheon with armfuls of lei pua kenikeni to give to the hosts, the chef, her friends, and any other lucky passersby. At Thanksgiving, she made sure her daughter (my mom), her four daughters-in-law, and her six mo‘opuna kaikamāhine (granddaughters) each had a fresh lei po‘o. Even the wooden ducks my family would bring out at Christmas were adorned with their own neck lei. Every canoe race, volleyball game, or track meet came with another Tūtū Bailey lei, including one for each of our lucky teammates and our coach. When we were on the mainland for college, she shipped lei po‘o and strands of pua kenikeni, carefully packed in wet newspaper lined with ti, all the way to the East Coast for our birthdays, including extras for our roommates.

At the time, I didn’t realize how lucky I was—things you routinely enjoy as a child often feel commonplace—making and giving lei was just the way our ‘ohana showed our aloha for one another and others. But I have come to understand the true event that receiving a Tūtū Bailey lei was and the extra care she took to make the whole experience of lei special and personalized.

My tūtū would gift her finished lei po‘o wrapped in ti leaf pū‘olo (a bundle containing a gift). She would tie the top with a nosegay in matching colors, a teaser to the treasure wrapped inside. Every detail in her lei was tailored specifically to the recipient and made with extra aloha and care.

My cousins, my sister, and I all learned by watching her meticulous but fast hands prepping and sorting the ferns and flowers. Only when her lei table was organized—stems trimmed to size, palapalai soaking in her plastic fish-shaped tub, and raffia hanging readily available by a clothespin—would she pull her metal stool, padded with layers of fabric, to the table to sit and start her lei wili. We would sit next to her on the cool cement basement steps and watch her hands work while she talked, her stories interrupted by polite requests: “Mele, can you clip a bunch of purple hydrangea from fridge for Tūtū?” A formal lesson from Tūtū was not offered often. There was usually a deadline, “Auntie is coming at noon for her lei.” But when she felt we were ready and if we caught her at that just right moment, she would say, “Come, it’s time for YOU to make a lei.” We stood, quickly grabbed the other (not padded) wooden stool, and hurried to sit by her side and wait for instruction.

Beyond the lessons on technique in kui and wili, we learned her incredible work ethic. Tūtū tackled her day by taking on the hardest tasks first. We observed her picking buckets of pua kenikeni blossoms before the sun came up, cleaning her palapalai patches with her Japanese sickle, watering her laua‘e (fern), loading her station wagon (with her vanity plate “Haku”) with tables and baskets and coolers of lei for a wedding or funeral, and sweeping the garage and cleaning her worktable after each lei, even when she made multiple lei that day.

Making lei is how Tūtū taught us to show aloha to our neighbors, community, and family. Decades later, many people tell me how the special touch of Tūtū’s lei made life celebrations (both happy and sad) or even just regular days more memorable.

Copyright © 2023 by Meleana Estes with Jennifer Fiedler. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.