IntroductionI am Taiwanese American. I’ve grown up with my grandma’s steamed pork bao as my favorite food since childhood, yet I’ve only been to Taiwan twice in my entire life. I can still get excited over a bologna sandwich, fight a stranger over the merits of Olive Garden’s breadsticks, and have heart palpitations seeing the green 59A exit sign toward Cracker Barrel and dreaming of their buttered cornbread. And yet, I still get harassed to “go back to my country” and ridiculed for my jet-black hair and tan skin. So where do I belong?

My mom and dad emigrated from Taipei, Taiwan, to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1985 and never looked back. Like many immigrants before them, they pursued the hope of opportunity, the promise of a better life. Spaghetti and meatballs replaced their childhood comfort of beef noodle soup. Iceberg lettuce with too much ranch dripping down its soggy leaves became their new palate cleanser of choice. The salad was a dish they gleaned from the fanciest restaurant in our neighborhood, Olive Garden, replacing the sweet acidity of lotus roots, fresh ginger, and cucumber of their adolescence. It was a means to adapt to their new life in America.

My parents learned English by watching Wheel of Fortune, and after they had me, they worked hours on end to land themselves in corporate America so they could provide the life they dreamed of for their son. For my hardworking parents, time for home cooking was limited, and so the food of my childhood became another avenue for them to raise an all-American kid. It brought McDonald’s into my life: Chicken McNuggets for days at a time, enveloping our 1990s Toyota minivan in the smell of fries. Trips to Skyline Chili after soccer practice, where the waitress, who still knows my name twenty years later, would pour a ladle of steaming-hot chili onto chewy spaghetti noodles, sending hints of cinnamon and cumin drifting into my uniform. It was through inconsequential dishes like these, the ones outside of our kitchen, that my love for food and flavor was shaped as I grew up in the suburban Midwest.

My relationship with Taiwan didn’t begin until later in my childhood, when my two grandmas, who both immigrated to America, became the two Trojan horses of all the things my parents left behind. On visits to my grandma on my dad’s side’s (nai nai 奶奶) home in Memphis, my morning sweet tooth for Cinnamon Toast Crunch evolved to include a savory craving for the smell of fried oil and greasy scallion pancakes topped with a soft-scrambled egg omelet. When my grandma on my mom’s side (po po 婆婆) moved in with us in Ohio, the kitchen island where spaghetti and meatballs once reigned now shared space with pulled noodles vibrantly colored with spinach in a delicate pork and daikon broth. These culinary treasure troves, like those of a lot of immigrant kids, were my secret. They were hidden from view in my day-to-day life of packed Lunchables and PB&Js, only to be enjoyed in the comfort of our family’s kitchens.

I didn’t start cooking until I was twenty. Until then, I would’ve proudly described myself as a professional eater but never a cook. My college roommate, Danielle, introduced me to home cooking, delivered serendipitously on a slice of toasted bread with buffalo mozzarella, fresh tomatoes and basil, and a drizzle of balsamic vinegar; I said, “Holy shit! You made that? In our tiny college kitchen?” Of all the things I had consumed up until that point, it was a piece of toast that sparked the idea for me that it was possible to re-create all the flavors I wanted to eat.

As I grew into adulthood, I was living the American Dream in San Francisco, the one my parents had worked so hard to make happen. At twenty-three, I was at the height of my career at Facebook, having just started designing what would become Facebook Live, when my dad began losing his battle to lung cancer. I put my life on hold and went back to Ohio to be with him, knowing he did not have much longer to live. The last thing he wanted to eat was, of all things, fried rice from P.F. Chang’s and mooncake from Taiwan that he had stashed in our house. As if morphine was a winter coat, I watched him shed it for a brief moment. When I brought his food over, he regained his appetite like an old friend entering a home on a cold day, eating his final meal that represented both his Lunar New Year as a child and his American guilty pleasure of Chinese takeout, all with a contentment that made me smile.

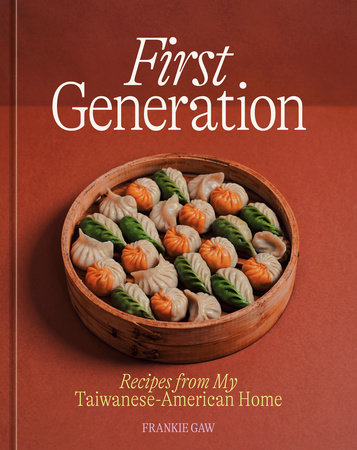

It took my dad’s death for me to begin to look inward to try to understand who I was and where my family came from, using the language I knew best: food. I would fly to Memphis every few months to learn my grandma’s recipes, starting with steamed pork buns. I would film her on my iPhone and have my aunt translate the recipes my grandma had scribbled on paper decades ago. After months of learning from my grandma and drawing from the textures and flavors of my own childhood, at age twenty-five, I posted my first photo of a steamed bun to Instagram, acknowledging the pride I felt in my cooking, and most importantly, my Taiwanese roots.

I wanted to write this cookbook to celebrate the first-generation Asian American experience—to reflect on an identity that exists in the in-between, that feeling I’ve always had of being culturally American yet not white enough, and too American to never feel quite comfortable in my own Taiwanese skin and ancestry. As I’ve grown up navigating my identity, food has been at the heart of my discovering both deep shame and overflowing pride.

This cookbook is a series of recipes and stories inspired by my family and the resilience of the immigrant spirit. I’ll tell about a young girl living in an abandoned mansion in the 1940s. An Asian family who adopts whiteness to survive in suburbia. A millennial who has it all, except his father. Immigrants—their food and their stories—are the heart of America and are what make this country thrive. This is just one of those stories, told by a proud, gay, first-generation Taiwanese American who loves food.

Copyright © 2022 by Frankie Gaw. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.