Introduction

Cooking and eating—and thinking about cooking and eating—is the Bisseret Martinez way.

The food I grew up with is heavily influenced by the African diaspora and Indigenous Mexican foodways: roasted sweet potatoes with braised greens, fried cornmeal-crusted tofu, and enchiladas in a smoky homemade guajillo sauce. (My Grandma Velia and Grandpa Jean, who represent the Mexican and Haitian sides of my family, respectively, are wizards with vegetables and herbs.) I’m so appreciative of my parents and grandparents for bringing all our heritage to the plate. But even more so, I am grateful they taught me to be curious about heritage beyond my own.

Our family is not composed of boring eaters, cooks, or even grocery shoppers, for that matter! My family goes to the source for all our foodstuffs—Chinese ingredients at the Chinese grocer, Nigerian at the Nigerian grocer, and the same for Filipino, Thai, Korean, Jamaican, Pakistani, Jewish, Italian, Black American, and Arab. This is possible when you live in a city like my hometown, Oakland, which has a diverse population. When I’m grocery shopping, I set aside any shyness, walk up to the people in charge, and ask about all their secrets: the best techniques for preparing their store products, their favorite ingredients, and what is freshest and in season now.

Once, when I was at Mi Pueblo, my source for Mexican ingredients in Oakland, I stood behind a woman in the checkout line and had my eyes set on her basket, which contained only one item: dried shrimp. Piles of it. Hmmm. I knew dried shrimp were used—especially in Asian and African cooking—for stocks, soups, sauces, and more, but this woman seemed to be stocking up for something special. I couldn’t stop myself: “Excuse me,” I said, pointing to her shrimp stash, “what will you be cooking with those?” She met my gaze and smiled big. Her answer: cucumbers and corn tortilla chips with a Mexican-style hot sauce, her favorite snack. She said, “You know, like nopales.” And I knew exactly what she meant, because I had these at many a lunch party and in Mi Pueblo’s prepared food area. For this dish, the cactus thorns are carefully removed from the nopales and then the nopales are diced into cubes with tomatoes, cucumbers, and lime juice. Oh! I went home and tried it. The saltiness and tang of the shrimp and hot sauce paired so well with the cool, crisp cucumbers. The toasty tortilla chips brought it all together in a crunchy bite. So good!

I really think that moment in Mi Pueblo sums up my approach to food and cooking: Be curious, and always keep your eyes and heart open to new flavors, ingredients, and experiences. When I get home from a farmers’ market or grocery store, I almost immediately dive into cookbooks and food media to learn more. I want to understand an ingredient’s origin, its traditional uses, and how those traditional uses have been modified in modern cooking. I compare what I was told with what I thought I understood and what others are saying. Then I go to the kitchen and start experimenting. It’s the best!

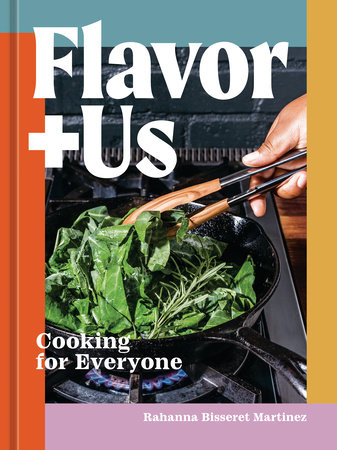

That spirit of exploration, my love of flavor, and my quest for culinary inclusiveness is at the heart of

Flavor+Us. My aim here is to pass on my knowledge to you—all nineteen years of it!—and forge all my geeky food studies and experiences into an easy-to-navigate, delicious-to-eat-from, socially-conscious cookbook.

Toni Morrison once said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

Flavor+Us is born from Toni Morrison’s mandate and my desire for a book that celebrates sustainable veggies, seafood, and meats, with a global palate.

If there’s one place that reflects the values of my book, it’s the corner of Ninth and Washington Streets in Oakland, where the Old Oakland Farmers’ Market sits across from Swan’s Market. The intersection is a few blocks from my old school, and I’d make pilgrimages there every Friday to spend my allowance on the year-round citrus and steaming chile y cheese tamales at the farmers’ market. Tamale in hand, I’d cross Washington Street to watch Swan’s fishmongers shuck fresh oysters, and florists present exciting, dramatic arrangements to supersatisfied customers. The two venues hummed with community—in the shared seating, in the dozens of languages being spoken, in the mix of spices flowing past my nose. That corner is everything I—and the friends I’ve made through cooking—want from a cookbook.

The recipes in this book include ingredients and techniques from all over the world. I’ve worked in fine-dining restaurants and believe that the skills I learned there can be useful in

everyone’s kitchen. When I say “fine dining” or “fine foods,” I really mean “high quality,” which to me must include fair trade and equitable labor practices. Systemic racism breeds mediocrity, so it is impossible for a restaurant to be the best of the best with a kitchen that is all male or all one ethnicity. When I visited the kitchen of Le Bernardin, one of the country’s most revered fine-dining establishments, under the leadership of Chef Eric Ripert, I was struck and encouraged by the diversity of the different teams and by how eager everyone was to share their techniques and methods with me. So, one of my goals with this book is to emphasize culinary techniques from many different cultures. For example, infusing an oil with herbs and citrus (see page 203) is a simple technique that can lead you in a million different directions. Pair it with Shorba Adas (Red Lentil Soup, page 99) or with Jalapeño Shrimp with Chard and Grits (page 129). Panfrying a cornmeal-dredged fish (see page 133) is a classic technique in Black American cooking. The dish works so well with Caribbean-influenced Curry Cabbage Steaks with Thyme and Red Pepper Butter (page 88) or the Quick Green Zesty Salad (page 79).

Yes, I’ve been on TV and staged (that’s French cooking lingo for interned) in Michelin-starred restaurants, but I got my start in my mom’s kitchen. I learned to cook with my mother, who is many things, but most relevant to this book, she is a traditional medicine herbalist and the center of our kitchen. She not only knows how to roast chiles until the exact moment before they turn bitter, she also sees the natural, edible world as a source of healing. With that comes an amazing sense of taste and a global mindset. When I was young, she took us to traditional Chinese medicine herbal shops, where I would look at everything around me and wonder how it all tasted and what it was used for. I got the message early that if it is part of the natural world, there is likely some use for it in eating, healing, or cooking.

Most of my mom’s cooking tools were glass, wood, or metal. If my sisters and I were reheating anything, it was typically on the stove top or in the oven. To this day, Mom never uses a microwave, food processor, or kitchen gadgets. (I think that was one of the things that excited me most—and still excites me—about going on food competition shows and working in professional kitchens: the gadgets and professional tools.) I mention all of this because I don’t want you to feel intimidated when I talk about technique. Having spent many eight-hour shifts peeling and prepping onions and breaking down tomatoes, I can tell you that lots of “technique” is just muscle memory! But it comes in handy in those moments when you

want to make something but don’t know where to start. If you’re feeling uninspired, sometimes thinking about how you want to prepare something (roasted, panfried, raw) will be easier than figuring out what to cook.

Copyright © 2023 by Rahanna Bisseret Martinez. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.