1

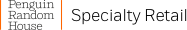

Out of the AshesSmokehouses, Storms, and Sauces When it rains, it burns. Is that a saying? Maybe not, but I feel that I can say it after the time I’ve had since I last reported from the pages of

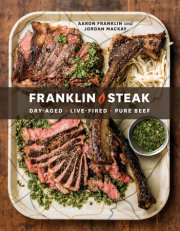

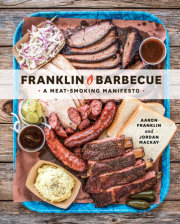

Franklin Barbecue and

Franklin Steak. While I’ve enjoyed my share of laughs and fun, now that I reflect on it, I’ve also had a stretch of struggles, just as you—and the country as a whole—surely have.

My wife, Stacy, and I are very lucky to have an incredible staff and loyal, loving customers who help to sustain us during challenging times. Nevertheless, I can easily imagine watching a zany Netflix series (like the oh so many we’ve binge-watched lately) based on the totally unpredictable developments that have occurred at Franklin Barbecue over the last seven years or so, including a fire in the middle of a rainstorm and the storm that is the pandemic. Cue a trailer featuring the high jinks surrounding a popular barbecue joint in never-a-dull-moment Texas. (I do wonder who the director would get to play Stacy.)

In many ways, this book has emerged out of the ashes, so to speak, after everyone’s normal way of life broke down during the pandemic. Like many of you may have experienced, I found myself with more time at home than I’d had since I was a child. At first, when none of us knew how long the pandemic was going to last, I headed into the backyard where my grills, smokers, and firepits live and started cooking for my family. I’m lucky to be able to say that this strange situation turned out to be positive for a number of reasons: it was a reminder of what I love doing, an outlet for my creativity, and a good excuse to spend time outdoors. Soon enough, I found myself on Zoom meetings, doing video cooking demos, and generally shifting to a distanced online world. When I checked in with my coauthor, Jordan, he was going through a lot of the same stuff: tons of cooking and sort of reveling in the free time and space we suddenly had while trying not to worry too much about what was going to happen to life as we knew it.

But before we go there, let’s rewind a few years so I can catch you up.

In 2017, we had a fire—a big fire. In what could be described as almost biblical circumstances—a driving wind and rainstorm powered by a massive hurricane hundreds of miles away—our smokehouse went up in flames. If the last thing you read about us was in Franklin Barbecue, you might have in mind the cowboy-like romance of how I cooked barbecue under the stars, espresso in hand, eyeglasses reflecting the flickering of a half-dozen roaring wood fires.

Well, that situation didn’t last for more than a few years. In fact, the cover of

Franklin Barbecue was photographed on the freshly poured concrete slab of what would become our new smokehouse. The main reason for building the smokehouse was both practical and legal. We didn’t own the vacant dirt lot on which we had been cooking. We rented it. But our operation was spread between two separate properties, which, it turns out, isn’t technically very legal. We had to combine operations into one property, a shift we had tried to make countless times. In the end, that wasn’t possible.

So, we built the smokehouse. Its unusual design—a two-story addition to the existing restaurant, with an industrial elevator to haul firewood and meats from ground-floor storage to a second-floor room packed with crackling barbecue pits— reflected the necessities of our unique property. It is built into a surprisingly steep hillside on the edge of a commercial block and is the only smokehouse I’ve ever seen located on the second floor of a building. On paper, I admit, this is a terrible idea. But up in the air was the only place to put it.

Property lines were not the sole reason to build it, however. The smokehouse was also an attempt to make life easier for me and the other cooks. This was all part of our effort to step up and act like a real, sustainable business versus a collection of pieces jury-rigged together. You see, when we first opened the brick-and-mortar restaurant, we cooked out of the back lot by necessity. The setup was very rustic, making it feel as if we were still part food truck. While the restaurant that we took over had been a barbecue joint, the owner hadn’t been cooking on offsets over live fire. Rather, he had two Southern Pride ovens, one he took and one he left behind. We had to cut out the back wall of the restaurant and get a slide truck in there to move that old oven out.

Late one night a few days before we were set to open, the inconvenient fact became clear that there was no place to put a couple of multi-thousand-pound barbecue pits. The only way we could set them up was to wheel the trailers right over. But that was tricky because you can’t have a door on one property, cross over to make food on a different property, and then cross back over to the original property to serve the hot food. Or at least you couldn’t with our permits. That meant cooking in the back lot was a necessity. (And we rented that spot for $200 a month in, ahh, the old Austin of 2010.)

Two days before we opened, I cut a back door in the restaurant with a Sawzall to allow access to the vacant lot from our restaurant kitchen. Cutting through the metal on the side of the building was so dang loud. It was late at night, so Stacy was outside the wall with blankets trying to muffle the noise. Of course, at the time, most of the people sleeping in that neighborhood were the homeless or prostitutes and drug dealers—but we didn’t want to wake them either!

There were no steps in the back lot, only gravel and dirt on the hillside—and it was slippery. When we had to add a new cooker to meet growing demand, I got railroad ties to terrace the hillside in order to fit more equipment. I’d be landscaping while cooking ribs. (Good thing a shovel is a multiuse tool.)

When we needed an office in our little shantytown, we added a trailer, which we still have. But, more important, we couldn’t get a truck to unload firewood where we needed it, so it had to be hauled in. And there was no place to roll dollies, so briskets got dropped off on the front porch every day, and I had to pick them up and carry each box to the refrigerator. It was hard on the body and took a lot of time. I did the work because it was

our business, but you can’t expect to hire people for heavy loading when it’s dark, dangerous, sometimes muddy or slippery, and completely brutal, physical labor.

I also hoped having a smokehouse that got us out of the rain, the wind, and the cold in winter would make our cooking more consistent. On the road to achieving that, though, the smokehouse made some aspects of our process

more difficult. When I was cooking in the backyard, there was a little picnic table nearby where I could sit with my espresso. All the cookers were arranged so I could watch them at the same time—five or six at once. It was really convenient. Not so in the smokehouse. There was no vantage point from which you could see all the fires, so they had to be checked constantly. It took about a year, but we finally got our habits dialed in.

Back when I used to cook ribs, three degrees of temperature variability was my target. I might have one cooker at 278°F and the other at 275°F, burning really clean. That’s not easy to do, and I was at the top of my game. When we moved into the smokehouse, I had to relearn everything because all the radiant heat from the cookers got trapped in the room, making the ambient temperature hotter than it ever gets outside, even in the dog days of summer. And, of course, we had to extend the smokestacks enough to stick through the rooftop, which changed the dynamics of their draw. Plus, it was flippin’ hot inside, just brutal—in the summer and in the winter.

Logistically, the smokehouse worked out great, and I was really happy with it, even if it slightly took away from the art of it all—but that’s just me liking things as basic and as simple as possible. Altogether, it was a good thing. It made work less hard for people, which was the goal. (But the unintended consequence of

that was that people didn’t work

as hard. Go figure.)

Now, the concept of building a wooden structure to hold several roaring fires might seem a little dubious. And, looking back, sure enough, it was.

Copyright © 2023 by Aaron Franklin and Jordan Mackay, New York Times bestselling authors of. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

![The Franklin Barbecue Collection [Special Edition, Two-Book Boxed Set]](https://images.penguinrandomhouse.com/cover/9781984858924?width=180)