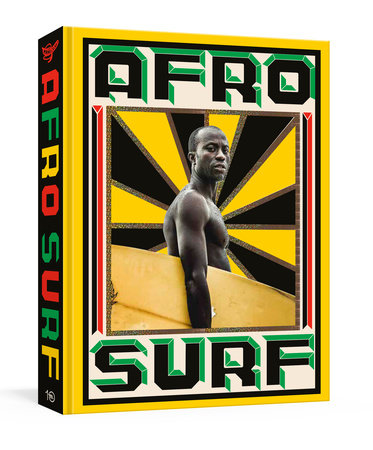

Popular histories of surfing tell us that Polynesians were the only people to develop surfing, that the first account of surfing was written in Hawaii in 1778, and that Bruce Brown, Robert August, and Mike Hynson introduced surfing to West Africa. All these claims are incorrect.

The modern surf cultures currently developing along Africa’s long shoreline are not something new and introduced; they are a rebirth—the remembering and reimagining of 1,000-year-old traditions.

The first known account of surfing was written in 1640, in what is now Ghana. Surfing developed independently from Senegal to Angola. Africa possesses thousands of miles of warm surf-filled waters, and populations of strong swimmers and seagoing fishermen and merchants who knew surf patterns and crewed surf-canoes capable of catching and riding waves upward of ten feet high.

Africans surfed on three-to five-foot-long wooden surfboards in prone, sitting, kneeling, or standing

positions, and in small one-person canoes. Despite Brown’s claim that The Endless Summer

(1965/1966) introduced surfing to Ghana, if viewers shift their eyes away from August and Hynson they will see the Ga youth of Labadi Village, near Accra, Ghana, riding traditional surfboards, which can still be found at some beaches. The ability of Ga men, in the film, to stand on the Americans’ longboards illustrates their surfing tradition.

Africans also rode longboards, about twelve feet in length, and used them to paddle several miles. English anthropologist Robert Rattray provided the best description and photographs of paddleboards on Lake Bosumtwi, located about one hundred miles inland of Cape Coast, Ghana. The Asante believe the anthropomorphic lake god Twi prohibited canoes on the lake. Keeping with divine sanction, people fished from paddleboards, called “padua” or “mpadua” (plural), and used them to traverse this five-mile-wide crater lake.

German merchant-adventurer Michael Hemmersam provided the first known record of surfing, which

is problematic, as he described a sport that was new to him. Believing he was watching Gold Coast children—who were probably Fante, in the Cape Coast, Ghana, area—learn to swim, he wrote that parents “tie their children to boards and throw them into the water.” Other Europeans provided similar descriptions. However, most Africans learned to swim when they were about sixteen months old, and with more positive reinforcement; such lessons would have resulted in many drowned children.

Later accounts are unambiguous. For instance, in 1834, while at Accra, Ghana, James Alexander wrote; “From the beach, meanwhile, might be seen boys swimming into the sea, with light boards under their stomachs. They waited for a surf; and came rolling like a cloud on top of it.”

There are also accounts of Africans bodysurfing. In 1887, an English traveler watched an African man named Sua, at home “in his element, dancing up and down and doing fancy performances with the rollers, as if he had lived since his infancy as much in the water as on dry land.“ As a wave approached, “he turns his face to the shore, and rising onto the top of it he strikes out vigorously with it towards land, and is carried dashing in at a tremendous speed after the same manner, as the [surf-canoes] beach themselves.”

Fishermen often surfed their six-foot-long paddleboards and surf-canoes that weighed about fifteen pounds. Accounts describe both from the Cape Verde Islands, Ivory Coast, Congo-Angola, and Cameroon, with the “Kru” canoes of Liberia particularly heavily documented. In 1861, Thomas Hutchinson observed Batanga fishermen from southern Cameroon riding surf-canoes “no more than six feet in length, fourteen to sixteen inches in width, and from four to six inches in depth” and weighing about fifteen pounds. Describing how work turned to play, Hutchinson wrote:

During my few days’ stay at Batanga, I observed that from the more serious and industrial occupation of fishing they would turn to racing on the tops of the surging billows which broke on the sea shore; at one spot more particularly, which, owing to the presence of an extensive reef, seemed to be the very place for a continuous swell of several hundred yards in length. Four or six of them go out steadily, dodging the rollers as they come on, and mounting atop of them with the nimbleness and security of ducks. Reaching the outermost roller, they turn the canoes’ stems shoreward with a single stroke of the paddle, and mounted on the top of the wave, they are borne towards the shore, steering with the paddle alone. By a peculiar action of this, which tends to elevate the stern of the canoe so that it will receive the full impulsive force of the advancing billow, on they come, carried along with all its impetuous rapidity. Surfing was a means for opening up economic opportunities. It allowed Africans to critically understand surf-zones so they could uniquely traverse them in surf-canoes, linking coastal communities to offshore fisheries and coastal shipping lanes. Atlantic Africa possesses few natural harbors, and waves break along much of its coastline. The only way many coast people could access the ocean’s resources was by designing surf-canoes that sliced through waves when launching from beaches. The surf canoes were also fast, agile, and maneuverable, allowing them to surf waves ashore.

Surfing was the intergenerational transmission of wisdom that transformed surf-zones into social and cultural places, where the youth holistically experienced the ocean. Suspending their bodies in the drink and positioning themselves in the curl, they learned about surf-zones by seeing and feeling how the ocean pushed and pulled their bodies. The youth learned about wavelengths (the distance between waves), the physics of breakers, and that waves form in sets, with several-minute intervals between sets.

Importantly, surfing taught these youth that to catch waves, one needed to match their speed; something Westerners did not comprehend until the late nineteenth century. Documenting how surf-canoemen utilized childhood lessons, an Englishman noted that they “count the Seas [waves], and know when to paddle safely on or off,” often waiting to surf the last and largest set wave.

In an age with few energy sources—when societies harnessed wind, animal, and perhaps river power—Atlantic Africans used waves to slingshot surf-canoes laden with fish or tons of cargo ashore, being the only people to bridle the energy of waves as part of their daily productive labor. Surf-canoemen floated colonial economies, transporting virtually all the goods exported out of and imported into Africa between ship and shore from the 1400s into the 1950s, when modern ports were constructed.

During the 1400s, surf-canoemen introduced Europeans to the pleasures of surfing, since at the time, few Europeans could swim well enough to surf. In 1853, Horatio Bridge provided an exaggerated account of surf-canoeing at Cape Coast, he wrote, “The landing is effected in large canoes, which convey passengers close to the rocks, safely and without being drenched, although

the surf dashes fifty feet in height. There is a peculiar enjoyment in being raised, by an irresistible power beneath you, upon the tops of high rollers, and then dropped into the hollow of the waves, as if to visit the bottom of the ocean.” Some surf-canoemen attached a chair to the front of their canoes, where especially intrepid white passengers could sit.

Surf-canoemen knew Europeans feared drowning and being devoured by sharks the instant they fell

into African waters. Using this knowledge, they inflated the tips received from passengers by engaging in nautical games of chicken, as Paul Isert observed on October 16, 1783, at Christianburg Castle, Accra:

In vain have Europeans tried to breast the breakers and to land in their own small pointed boats. These have almost always capsized . . . The blacks now started to prepare themselves to breast the breakers. The captain of the canoe made a short address to the sea, after which he sprinkled a few drops of brandy as an offering. At the same time he struck both sides of the canoe several times with his clenched fist. He warned us Europeans to hold fast. The whole performance was carried out with such gravity that we felt almost as if we were preparing for death. An additional cause for alarm is that, having started to go through the breakers, they must often paddle back again because they had not timed it to the right moment. They are said to do this often deliberately in order to torment the whites in the breakers for a long time, so that in acknowledgment of their great struggle they would be given a larger bottle of brandy. In a few minutes, however, we were safely across and our boat was on the sand. As surfers must realize, these Ga surf-canoemen prolonged Europeans’ time in surf-zones by pretending their timing was off, as “it is customary” on such occasions for “each passenger” to “make a handsome present” to the surf-canoemen.

Copyright © 2021 by Mami Wata; Foreword by Selema Masekela. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.