Coming Full CircleIn the late summer of 2019, I hit a wall. I felt cruddy after years of eating everything that I wanted, all in the name of professional research. A strange bulge in my lower abdomen sent me to the doctor, who suggested that I had a hernia, then ordered an ultrasound and referred me to a surgeon. That took several weeks, during which my anxiety level rose as I consulted “Dr. Google” and my family. The bulge subsided by the time I met with the surgeon, but I still didn’t feel great. He reviewed the ultrasound, examined me, and said, “You don’t have a hernia. Tell me what’s been going on.”

Verging on tears of relief and in an outpouring of what probably sounded like gibberish, I explained my career and stress level, the result of a busy work life filled with traveling and consuming too much and too many foods not meant to be eaten together. Wherever and whenever, I ate out of curiosity, obligation, and pleasure. Also, my fifty-year-old body was going through perimenopause. Hormonal shifts were wildly driving the bus. “I think I need to slow down, rest up, and change my diet,” I blurted as he nodded. The emotional unloading cleansed me like a terrific shower.

Up to that point, my omnivorous meals included some whole grains and decent amounts of vegetables. Evaluating my options, I ruled out overly regimented diets because I’m not a virtuous eater every day (rice and sweetened condensed milk are wonderful). Raised Catholic, I always went without meat during Lent, but even then, when I refrained from it, I enjoyed plenty of fish and didn’t gravitate toward exclusively plant-based foods. However, decades of cooking had taught me how a little fish sauce, chicken, or pork can turn a meh dish into a wow one. My problem was that I didn’t cook and eat that way enough. What if I simply prepared food with less meat and upped my vegetable intake?

I re-visited and re-imagined favorite Vietnamese dishes to spotlight members of the vegetable kingdom. Regardless of whether the dish was vegan, vegetarian, or vegetable-forward with some meat, my overarching goal was to build savory depth and fun experiences, respectively described as đậm đà and hấp dẫn, Viet terms that refer to tastiness. I had a blast veganizing fish sauce, noodle soups, and other popular dishes as well as devising recipes to celebrate Vietnamese ways with produce and grains. Sometimes I created a new dish, such as Char Siu Roasted Cauliflower (page 227), which you may stuff into steamed buns (see page 117) or banh mi (see page 128).

I also reached back to my high school days, when, after my four siblings had left for college, my parents and I shared many low-meat meals. I thought those were anomalous, but, in retrospect, the meals embodied my parents’ cultural food pleasures, which were homey, comforting, and humble. Recipes such as Peppery Caramel Pork and Daikon (page 249), Creamy Turmeric Eggplant with Shiso (page 203), and Greens with Magical Sesame Salt (page 201) offer my modern takes on enduring savors.

I realized that I didn’t have to give up foods that I love, but rather needed to better respect and cultivate the exciting flavors, textures, and colors in plants. Compared to what I had cooked in the past, the new dishes were lighter and more refreshing. They tasted delicious, and I felt good without feeling deprived. Choosing more plants over animals seemed natural, a cinch. I was so proud of myself. I checked in with my mother, pitching my life-changing ideas about Vietnamese low-meat and vegetarian cooking. She was happy that I felt well but also said, “Meat was expensive in Vietnam. We cooked with mostly seafood and vegetables. That’s how it was. We ate more meat after we came to America because here, meat is more affordable than seafood.”

I was six years old in 1975 when we fled Vietnam and resettled in the United States. My early memories of food spanned the Pacific—from the open-air markets of Saigon to the supermarkets of Southern California. I wasn’t aware of the shift in my mother’s cooking as I delighted in her rotation of roast chicken, beefsteak, grilled pork, and other meaty delights. Veggies were on the table but, as it turned out, not as much as they traditionally would have been. My siblings and I also reveled in having greater access to soda pop, potato chips, butter, and sugar. We had changed our eating habits. I had gotten derailed, taken a decades-long detour, and finally returned home at the table, so to speak. Switching to a plant-forward diet in midlife basically brought me back to my cultural food roots.

Of course, Vietnamese cuisine is not all about beef-laden bowls of pho and meaty stuffed sandwiches. Viet culinary culture has been and continues to be shaped by scrappy cooks who make the most of limited resources, the majority of which are harvested from the earth. The cuisine—with its inherent customization, rich Buddhist traditions, and emphasis on vegetables, herbs, fruits, and plant-based proteins—is a natural mechanism for cutting back on meat and developing a greener approach to living.

I’m not alone in adopting a pro-produce lifestyle. Plant-based foods have been trending upward for years, and more Americans are moderating meat consumption but not giving it up altogether. Buddhism has historically guided Viet vegetarianism, but in Vietnam, some people are choosing it for health and environmental reasons; organizations such as Green Monday Vietnam plug into the global Meatless Monday campaign.

Curious about how such trends aligned with my online community, I surveyed folks. Of the more than 1,500 respondents, nearly one-fourth were flexitarian, and two-thirds were omnivores. More than half saw themselves eating less animal protein in the future and, increasingly, people were diversifying their cooking to welcome diners with mixed dietary restrictions or preferences. More than three-fourths said they would be interested in a vegetable-forward cookbook. Their many thoughtful suggestions matched my lifestyle and culinary philosophy of balancing new and old concepts in meaningful, practical ways.

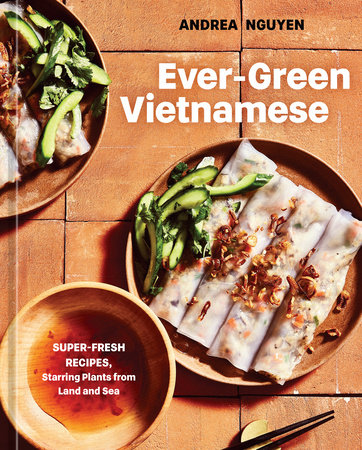

Enthusiasm for vegetable-centric cooking seeded and fueled this book’s creation. I made this for you, me, and others for whom we’ve yet to cook. You don’t have to be Viet to identify with

Ever-Green Vietnamese. You just need to explore the potential of vegetables from land and sea and, if you’re open to it, occasionally leverage the power of animal protein. That lies at the heart of my undogmatic plant-focused kitchen, which dovetails with the flexibility found in much of Viet cooking.

In Vietnamese,

chay means “vegetarian.” This book isn’t 100 percent vegetarian, but the word appears often. When attached to a food term, chay signals a plant-based iteration. For example, nước mắm chay and phở chay indicate vegetarian or vegan fish sauce and pho, respectively. Vegetarian eateries are nhà hàng chay (a formal restaurant) or quán chay (a casual joint). Vegetarianism isn’t marginalized in Vietnam. People who ăn chay (eat vegetarian) may be full-time, part-time, or occasional vegetarians. They may abstain from eating animal protein for religious, health, or ecological reasons. They may eat mostly veggies along with some seafood. Or, they may tinker with vegetarian cooking to create trompe l’oeil dishes that make people do double takes. And, if there’s an agenda in promoting Viet vegetarianism, its approach isn’t moralistic but rather focused on gentle persuasion. Cue Buddhist vegetarian restaurants and temples that generously offer tantalizing fare to anyone interested. Perhaps they’ll coax people into leading kinder lives? Chay foodways welcome everyone into the kitchen and to the table. That open spirit guides this book. As a non-extremist who can’t stop loving food and cooking, I share this with you: A plant-forward diet has helped me better negotiate midlife physiological changes and perimenopausal symptoms. I also shed about fifteen pounds in the process.

Copyright © 2023 by Andrea Nguyen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.