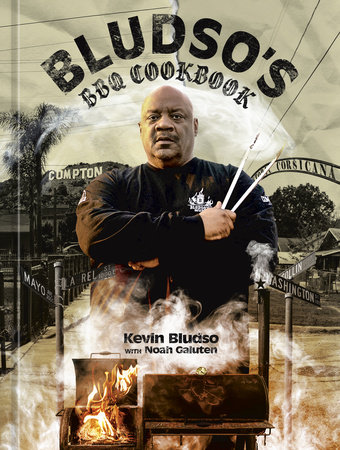

IntroductionI was born and raised in Compton, California, with a police officer father and a Black Panther–supporter mother. Every summer to stay out of trouble, I went to Corsicana, Texas, to work at my granny’s illegal, bootleg BBQ stand.

I always just say that I’m so lucky to live the life I’ve lived. To be from Compton, to be born and raised with people like Dre and them in the city, in the concrete jungle, but then on the flip side to be able to be in the country every summer, to walk around barefoot, and go crawfishing and all that. Getting to grow up in both California and Texas gave me a whole different outlook than if I had just been raised in one place, and that’s something I’ve been able to carry throughout my life. I just really think everything happens for a reason. Now I look back, and I’ve opened BBQ restaurants all over the world, I’ve gotten rave reviews from legends such as Jonathan Gold, I’ve hosted TV shows, I’m a two-time winner of the Steve Harvey Neighborhood Awards for Best Barbecue Place in America, and now I get to chill out and live in the country in Texas.

In this book, I want to teach you how to kick back, have fun, and make some good-ass BBQ. Then I also want to show you how I get down in the kitchen, too, cooking up way more than just BBQ. But for me this isn’t just a cookbook. I also want to tell a story. I want to tell you about the family history, how we started, how we came to this, and a few of the things I’ve learned in my fifty-five years.

Shit Talking, Cooking, and Partying Lessons with Willie Mae Fields I call her my granny, but Willie Mae Fields was really my daddy’s auntie. She’s the one who taught me how to BBQ. I swore up and down to her that I’d never go into the restaurant business. But Granny always said, “You’re gonna have to own your own business because you’re too much of an asshole to work for anybody else.”

That first summer I went to Texas to stay with Granny, I was eight years old. I’ll always remember that ride in her ’74 gold, four-door Lincoln Continental. I was in the car with her, Aunt Alice, and Mr. Fred. (I still have no idea who Mr. Fred was. I don’t even think he was family!) They were just partying, drinking, and driving, blues all in the car. The cooler was full of hog headcheese and sandwiches, and I was like, “What the f*** did I get myself into?”

Then in the house was Granny’s crazy-ass husband, Johnny B., who was shell-shocked from the Korean War. So she’d say, “You want to stay here with this crazy motherf***er or you want to work with me in the morning?”

So I started working with her, getting up at six o’clock in the morning and going to her illegal BBQ restaurant on the weekends, with gambling going on, with no permits or health department or anything. She called it Little Rascals, and I watched her work that stand with Aunt Jean and Aunt Alice. It was just the three of them running this restaurant so incredibly. And all they did was cuss out each other all day. As a kid I’m watching this shit, like “Wow.” I wasn’t used to sitting there with somebody cooking, telling a story, talking shit, laughing, playing the music all loud. I wasn’t used to that, and that’s what made it better. You see, my parents were young. They were still working, still humping, so when I would go out to Texas, it was something special. I was hooked right away, and I went back every summer.

Granny did so much for so many people. She put people up, fed people. She was a legend in Corsicana. She was ninety-five years old when she died. Something like fifteen thousand people lined the streets of the town for her funeral procession. Everybody knew Willie Mae Fields. But don’t get me wrong, Granny was a hustler too. She ran her little businesses in the back—her after-hours club, some other little red-light shit. No matter what, Granny didn’t believe in being broke.

She also had a small juke joint next to her house where she could probably fit fifty people at a time, selling BBQ, Crown Royal, Schlitz Malt Liquor, gin, and whatever else. She called it The Halfway House. The juke joint was really long, kind of like a house on one side where you’ve got the kitchen and all that. At one end was this tiny waiting room that had a little speakeasy door so she could look through it and make sure you weren’t the law. After she’d let you in, you’d walk through the kitchen, where it was hot as hell. Past that there was a bar area with a couple of rooms off to the side in case you wanted to do some . . . other stuff. She had AC in all the rooms and in the bar, but it was all window units. Wasn’t no central air. But everybody would party. The back was wide open and had a jukebox, though she would have bands in there sometimes—blues bands and stuff like that.

But shit, she wouldn’t let me drink with her until I was, like, fifteen or sixteen, and even then it was just a beer or something. But I loved being out there in Texas with her. She taught me cooking, but she also taught me work ethic. She’d be up all night cooking a brisket—and having a cocktail— until two o’clock in the morning, but she’d still get up at six no matter what; and I’d have to get up with her. “You don’t work, you don’t eat,” she’d say. We’d be smoking brisket, cooking collards, the whole thing. I still cook my greens the same way Granny cooked hers. I cook my brisket the same way. Eventually, I was the only other person she trusted to cook a brisket.

Granny also taught me the value of family. When my father or my grandmother—my dad’s mom—would come down from LA, that was huge. Granny couldn’t wait to show them a good time. She would prep food for a whole week. I’m talking, like, a hundred pounds of chitlins. She would just prep these massive amounts of food for the whole time that people were there. She and my grandmother loved each other to death, but they couldn’t get along for more than five minutes. My grandmother would drive all the way out from LA just to argue with Granny. There was so much love, and sometimes they showed it by talking shit with each other.

But talking shit was a big part of our family. I was Granny’s baby, and she still always used to talk about my big nose. She’d say, “God wanted you to have a big nose so you could smell the bullshit.” Some people trip on what they can’t really change. In my family you couldn’t grow up with a damn complex, because they talk about everything. They talk about each other’s kids, each other’s wives, each other’s husbands,

everything. Some of my best jokes come from me being in Texas with my granny, just watching the family clown and talk shit. It goes on to this day. My uncle still calls just so we can cuss each other out and laugh about it.

When Granny was growing up in the 1920s, her mom was working for someone on the other side of town—somewhere close to Corsicana, I’m not exactly sure where—so as a kid Granny went along to work with her. Granny started playing with this other kid named Bill, and they developed a friendship at a time when Black and white weren’t supposed to be friends. They were five or six—little kids—and they had a friendship that went all the way until Granny passed away at ninety-five. Bill didn’t live another year after she died. They were real close. That taught tolerance too. She’d say, “Bill has some good-ass racism jokes.” But then she’d tell me, “You don’t need to get mad; just flip it around!” They would sit around and just, as grown-ass people, crack jokes on each other. He’d have the nerve to be cracking Black jokes—well, they didn’t call them Black jokes, but you know what I mean—and he’d tell one, sitting right next to me and be like, “You get that one?” And then his laugh would just make

me laugh. But my granny loved him so much, and I loved him so much. They made it so that I didn’t give a f*** if it was a racist joke or whatever, as long as it was from the heart and it was for comedy. There’s a difference if you’re saying shit and it’s from hate. If it comes from hate, it’s not a joke. But Granny taught me that there’s humor in everything. Certain things are serious. There’s no doubt about it. Certain shit is serious as hell. But you’ve got to find some humor. Just like you find the pain and you deal with it, you’ve got to find the humor in everything too.

At Granny’s funeral, Bill came up and he couldn’t talk. Our family, Unc and everybody, they came up and held him so he could speak. He loved us so much and loved Granny so much. He could barely talk. He just said, “No more jokes,” and everybody knew what that meant. There wasn’t going to be any fun anymore. Then he just kept saying, “She was my friend . . . she was my sister . . . she was my friend.” They were real friends. People say, “Oh she lived to ninety-five, she lived a good life.” And yeah, she did, but that doesn’t make it easier for the people she left behind. I had that woman in my life for nearly fifty years, and I thank God for that.

Copyright © 2022 by Kevin Bludso with Noah Galuten, photography by Eric Wolfinger and Demetrius Smith. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.