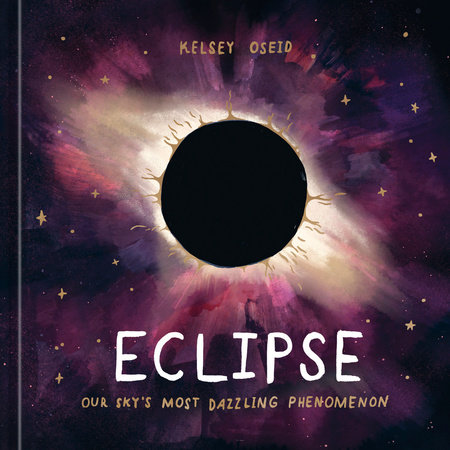

IntroductionAncient cultures imparted a higher meaning to the phenomenal celestial events that are eclipses. How could they not? When the sun disappears in the middle of the day, or when a vast shadow bathes the moon in a bloodred glow, who could resist drawing the conclusion that something bigger is going on?

At one time we believed in mythical beasts swallowing the sun whole, angry gods turning the moon crimson to signal earthly impending doom . . . But in the modern world, with our ability to predict when eclipses will occur and our knowledge of the mechanisms making them possible, the meaning of eclipses has flipped. Instead of signaling something wrong—Where is the sun going? What is happening to the moon?—they show us that everything’s working just as we expect it to (an eclipse, right on time!).

Since early in our human consciousness, there have been two celestial bodies that most Earth dwellers can observe and that behave predictably on a daily basis: the sun and the moon. In fact, the brighter of the two—the sun—was the very basis

of the day. In the mornings, the sun rose in the east. By nighttime it had traveled across the sky and set in the west. The moon was a little more changeable, since as it passed through its phases its appearance transformed, little by little each day, but this cycle takes only about 29.5 days and is easily tracked. While the moon did seem to disappear once each cycle, during the new moon phase, this was eased into over several days and was considered predictable very early in human history. (Humans tracked the moon through its phases as early as thirty thousand years ago, as evidenced by ancient lunar calendars etched into animal bones.)

The Nebra Sky DiskThe Nebra Sky Disk is a testament to the important roles the celestial bodies played in the lives of our ancestors. Dating back to 1600 BCE or possibly earlier, the foot-wide bronze disk contains depictions of the sun and stars, as well as coded references to the timing and location of the setting of the sun in the region of modern-day Germany where the disk was found. The crescent shape is variously thought to depict a phase of the moon or a solar eclipse.

Eclipses, unlike moon phases, seemed so unpredictable as to be random. Confounding factors like weather (it is harder or even impossible to see a lunar eclipse on a cloudy night, for instance) and geographic location (many total solar eclipses are visible only from very particular places on Earth, and sometimes in the middle of the ocean where there’s no one to see them at all) would have made eclipses seem even more random, more extraordinary—and more ominous. And unlike the phases of the moon, happening gradually over the course of the month, eclipses were sudden. A solar eclipse looked like a vicious bite was being taken out of the disk of the sun, seemingly out of nowhere, and a bloodred lunar eclipse dimmed the moon on the very night it was at its fullest. The apparent randomness was all the more ominous when it seemed to threaten the otherwise comfortably predictable motions of the heavens.

The exceptional strangeness of eclipses and the intense emotional reactions they evoke are probably what motivated many ancient cultures to keep careful records of them. The ancient Mesopotamians kept such records; they are credited with observing and spreading the knowledge of the way eclipses recur periodically. For although eclipses do not occur on a daily basis, like the rising of the sun, or a monthly one, like the phases of the moon, they do follow a pattern. They turn out to more or less repeat on a cycle of 223 synodic months (that is, lunar months, measured from one new moon to the next), or about eighteen years and eleven days, which is sometimes called the saros cycle; this unit of time is one saros. Every saros, or approximately every 6,585 days, a nearly identical eclipse will occur, in which Planet Earth aligns with the sun and moon in almost the same way, and the eclipse takes place along the same geographical path.

It was not necessary for the ancients to understand the shape of the solar system or even that the Earth was not at its center in order to use this cycle. But understanding of the saros cycle began to chip away at the notion of eclipses as bad omens. As time went on, astronomers devised endlessly convoluted models of the sky in an attempt to further explain the motions of the heavens—models that were unnecessarily complicated in order to justify what was going on in the sky. By the eighteenth century, humans had moved from a general belief in a geocentric model of the universe (with Earth at its center)—famously championed by Claudius Ptolemy—to the Copernican heliocentric model (with the sun at the center of the solar system). The motions of the heavenly bodies became settled fact in the common astronomical understanding. Math could now be used to predict the relative positions of the sun, moon, and Earth.

And so, with increasing accuracy over time, astronomers were able to calculate the precise dates, times, locations, and characteristics of future eclipses. Today, sophisticated calculations make it possible to spin out eclipse predictions, accurate to the second, for millennia into the future.

Copyright © 2024 by Kelsey Oseid. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.