Introduction

For the Love of Hot WaterThe world’s first official national park was made because of hot water. Awestruck by the wonder of natural springs and geysers, President Ulysses S. Grant signed an act to establish Yellowstone National Park in 1872. It was the first major action by the US government to protect and recognize the importance of nature and its connection to people. My ancestors, who settled in Montana’s Madison Valley in the 1860s, visited the park as a family in 1873, first by wagon and then on horseback. We have journals from their visit, testimonies of wonder and fearsome awe: “It holds one spellbound . . . it is so busy and spiteful that it is much admired. . . . Wonderful in the full sense of the term. I do not consider myself competent to describe any of the views we find. Anyone who knows how grand and beautiful they are, must see for themselves.”

A reverence for the outdoors and a sense of adventure have continued to shape our family’s pastimes. Hot springs were usually a part of our family trips when I was growing up. We’d hike into wild springs or take a soak after backcountry skiing. I learned to swim in a hot springs pool, my arms stuffed into water wings. One time, on a road trip across Utah, my hair turned copper red from the iron content in a hot spring. I grew up in a culture of outdoorsiness: we spent school breaks on long trips bicycle touring, kayaking, backpacking, or skiing. The hot springs were my first experiences in nature where we did nothing but rest. At home, I found comfort in a hot bath. When I had a headache or heartache, I’d spend hours in our claw-foot tub.

My parents, both schoolteachers, moved our family of three overseas when they accepted jobs in international education systems. When I was fourteen, we moved to rural northern Japan, where the hot bath culture became a part of our weekly routine. We’d walk past farmland into our neighboring community, with a little pail for our towels and soaps. We’d scrub and shampoo ourselves next to elders, teens, and mothers with their children, our voices hushed in the steam. Then we would enter the pools and soak. As a college student working in food service at a mountain lodge in Idaho, I’d visit a riverside hot spring before or after my longest shifts.

Each hot springs story starts deep underground, where groundwater or rainwater trickles through subterranean faults and fissures, mingling with magma and heated rocks. Pressure forces the heated vapors and liquids upward, back toward the surface. It can take the form of geysers, fumaroles, and mud pots. Sometimes, miraculously, it creates hot, mineral-rich water of various temperatures and temperaments, some perfect for humans to soak in.

To soak in a hot spring is to be cradled and cared for by the dynamic forces of the planet. It is its own meditation. I love how my body becomes reacquainted with itself in hot water. I love the contrast between hot water and cold air, the way steam and sweat become indistinguishable. My cheeks and skin soften; my muscles no longer tense from thoughts. I can see it in other people, too. Their eyes are less quick, their brows slack. No one ever seems to be in a rush at a hot spring.

Soaking is a singular human experience: it promotes presence, relaxation, and reflection. It removes pretenses and distractions. It gives us the opportunity to be a citizen of nature, ritual, and community. I’ve learned in my travels that each soaking experience is unique, tied to culture, traditions, and geography.

I’m now a photojournalist living in Maine, where there are no natural hot springs. Most of my projects are magazine and newspaper stories about the ways we humans connect to the natural world. I spend a lot of time with small-scale farmers, fishers, ranchers, foragers, and artists—people who have maintained a strong connection to the land, who understand how much we rely on it for our survival and well-being. They’ve shown me not only how to live gently with nature but also how rare it is to live that way. I’ve seen how humans set themselves apart from wilderness, seeing it as something to exploit, dominate, or fear. We’ve taken for granted the consistent providence of nature, forgotten the everyday natural phenomena that shape our lives with grace and bounty.

I believe that one of the solutions to environmental degradation is to restore our own relationship with land, water, plants, animals, the cosmos, and each other. As more populations urbanize and as technology dictates and commands more of our lives, we need reminders that we exist alongside and within nature. There are many ways to do this but few as immediate and clear as taking a soak in a hot bath, no matter where you are in the world.

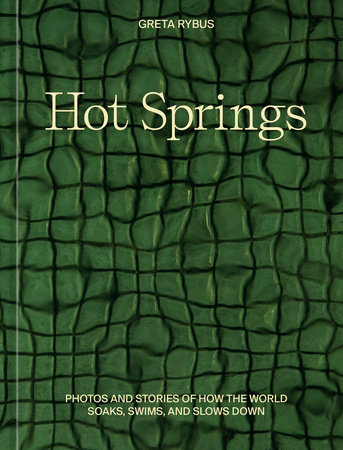

This book is an exploration of hot springs and the various, spectacular ways this geological marvel can express itself with the collaboration of humans. Some look like palaces, others like a hole in the ground. Some feel like a party, others like a prayer. But every hot spring has the solace of heat, warm water that holds you and forces you to be present. Every hot spring is said to have healing properties, to be filled with elements dragged from inside the planet. These gathering places form odd communities, giving us a sense of belonging to each other and the earth.

Copyright © 2024 by Greta Rybus. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.