IntroductionThe story begins with a bad sandwich. I grew up in rural Virginia, in the tiny town of Free Union. My formative food experiences were at shabby, family-run country stores—part gas station, part convenience mart, and part takeout counter. They sold beer and gas, lures and ammo, chili-cheese dogs and biscuits with white gravy. Some sold the delicacy that my mom calls “rat cheese,” a wheel of fake cheddar that sweats all day on the counter, typically unwrapped and unrefrigerated, to be purchased by the hunk and eaten with some saltines. It’s the dairy equivalent of a loosie cigarette.

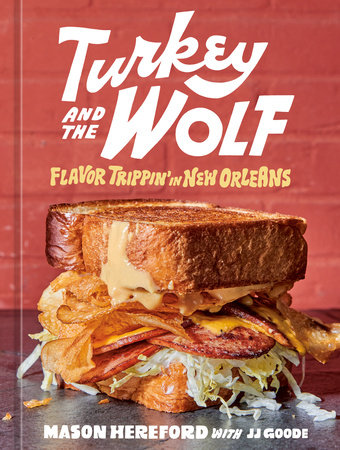

Sometimes when we were hard up for lunch, we’d stop at one of these stores and my mom would grab us some bologna sandwiches. I hated those bologna sandwiches. I hated the texture of flabby off-brand cased meat. I hated the yellow mustard (which I couldn’t stomach unless, for some reason, it was on a McDonald’s burger). The only way I knew how to turn that sandwich into something worth eating was to load it with salt-and-vinegar potato chips. Never would’ve guessed that some twenty years later, my version of that bologna sandwich would be featured in magazines, on food TV shows, and, most important, in a mayonnaise commercial.

Mostly, though, I loved the food in those stores. There’s Wyant’s, in White Hall, Virginia, which has been run by the Wyant family since 1888 and where the sausage biscuit never fails to hit the spot. There’s Brownsville Market, in Crozet, which has a hot case stocked with broccoli-cheese casserole and fried chicken. And there’s Bellair Market, in Charlottesville, where every week for a decade, I ordered a sandwich called The Jefferson: turkey, cheddar, and cranberry relish on a French roll, slathered with an herb mayo that shows up in my dreams (and on page 104).

The store that had the biggest influence on the way I cook today didn’t make food at all. Maupin Brothers Store was a few minutes by foot from our shabby A-frame in Free Union. We went every day, often several times a day. We were there so much that it became like an extension of our home. Della Maupin (we all called her “Miss Maupin”); her husband, Kemper; and their son Mike ran the store. They let my mom run a big tab. They ratted out my brother when he pulled my mom’s rusty GMC Suburban into their parking lot before he had his license. They were family.

The most memorable times were in the mornings. Mom had to get four kids ready for school, and when we missed the bus, which happened hilariously often, she would cram us in the GMC, spill coffee on herself, then make a beeline to Maupin’s. She’d let the truck idle in the lot and set us loose in the aisles. Some days, I’d grab a Jimmy Dean sausage biscuit or bean burrito plucked from the freezer case and thaw it to perfection in the microwave. Other days, I’d pop open a can of jalapeño-flavored Vienna sausage, because even as a young kid I had a very refined palate. Often, I opted for an ensemble breakfast: a bag of Doritos, a Snickers bar, and a can of Mr. Pibb. I always tried to make the food last the entire drive, and the ultimate was pulling up to school as I took my last bites—two Doritos at once followed by the center cut from the Snickers chased by the final sip of Pibb.

Junk food wasn’t my only muse. My fancy grandma, who asked us to call her Ann, was a badass cook: I’m talking game birds, duck fricassee, and snapper with herbed lemon butter. My mom still has Ann’s dictionary-thick recipe book, a hodgepodge of newspaper clippings and handwritten instructions. My mom also has her own mother’s recipe book. Her mom’s name is Anne, too, but she always went by Grandmommy. Grandmommy is as country as Ann was highfalutin. Her book is full of recipes, like cornpone, kraut dumplings, and hickory-nut loaf cake, written in her looped scrawl on paper that’s now yellowed and cracked. While Ann was making sure her table was set with the proper flatware, Grandmommy was rolling by the fridge to snack on raw hamburger meat sprinkled with salt and pepper.

My mom cooked food that was somewhere in between. It wasn’t fancy, and it reflected the same sort of practical considerations that brought me to Maupin’s for breakfast. She made an amazing dish of chicken with evaporated milk and apple juice concentrate. She melted American cheese on broccoli to serve with frozen fish sticks, and used Rice Krispies as a crust for baked chicken thighs. She made a special-occasion chicken curry with peas that would rock me every time. Then there were burnt tomatoes: a kind of magical casserole made from sliced, flour-dredged, pan-fried tomatoes that are sprinkled with sugar and baked to hell. She still makes them for Thanksgiving every year, and even though her son, the chef, cooks the rest of the meal, her burnt tomatoes are always the best thing on the table.

Still, I definitely didn’t have designs on being a chef. Right after college, I moved down to New Orleans, which I knew practically on arrival would be my forever home, and realized pretty quickly that I wasn’t going to be using my art history degree. My first job was as a door guy (think Swayze in Road House) at Fat Harry’s, a bar in Uptown. A few months later I became a cook there, and eventually a really crappy bartender—top of the totem pole, as far as the money was concerned.

That’s where I learned to cook—making burgers for the oddball regulars and cheese fries for the budding alcoholics at Tulane and Loyola. It was there, among the deep fryers and endless shots of Grand Marnier, where I became entranced by the alchemy of cooking, by how a little mustard wash, flour, and bird meat could enter a vat of bubbling oil and emerge as chicken fingers. When it was slow, the manager, Joey, would teach me all sorts of cool stuff that was definitely not on the menu, like how to fry soft-shell crabs and make barbecue-shrimp pistolettes. At some point I realized, cash tips be damned, I wanted to cook.

After a year at Fat Harry’s, I scored a job as a line cook at Coquette, a cool bistro in the Garden District that crushed at turning local meat and produce into inventive Southern food. I stuck around for six years. By the time I became Coquette’s chef de cuisine, I had learned to do some pretty neat chef shit, like taking modest stuff, like fried chicken or catfish, and dressing it up, and taking fancy-sounding stuff, like veal sweetbreads or beef tartare, and dressing it down.

Creative freedom and youthful enthusiasm kept me going despite years of eighty-hour work weeks peppered with hangovers, eating over trash cans, and broken cigarettes. Yet what actually got me through it was the people, the post-work revelry, the realization that we had all somehow found jobs that let us pay our rent without really growing up. I don’t remember, for instance, the choreography that allowed five grown adults in a tiny kitchen to put out hundreds of meticulous plates on busy nights. But I will never forget the fun: the time my fellow cook and close pal Richard Horner woke up after his first Mardi Gras with a mysterious pain in his shoulder, which turned out to be a tattoo that read “Kara Anderson is Hot Sauce”—even though he can’t remember ever meeting Kara. Still, she did friend him on Facebook months later. Needless to say, he was late to work that day. Or the time some silly goose sucked down a whippit from the iSi gun that we employed to make foamed horseradish cream, right before the Friday dinner rush, and brought the kitchen to its knees for a spell. (Again, I’m sorry to everyone who worked or waited too long for their food that night.) Or how every Sunday night, we’d meet at the bar down the street and stay for hours and hours after they locked the doors for last call, talking loud, ripping cigs, and dancing to Sugar Hill Gang, as if we hadn’t just put in fifteen hours on our feet. These were the same friends who joined me when I set out to open my own place, which we decided would be as much about serving good food as it was about bringing the party to work and figuring out how never to do another fifteen-hour day ever again.

Copyright © 2022 by Mason Hereford with JJ Goode. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.