Preface

Today, bourbon is the most popular, coveted, talked about spirit in America, but not long ago it was a liquor-store wallflower. When I worked in downtown Washington D.C., in the early 2000s, the liquor store around the corner from my office carried A.H. Hirsch Reserve 16-Year-Old, one of the all-time legendary bourbons, for about sixty dollars. Bottles of Willett Family Estate, including near-mythical single-barrel selections such as the Iron Fist and the Velvet Glove, sold for about the same. Even Pappy Van Winkle’s Family Reserve 23-Year-Old was going for a few hundred dollars. Though “going” is not quite the right word; no one wanted expensive bourbon, so the bottles sat there, gathering dust.

It sounds glorious. But I also remember how hard it was to find a bar with a decent selection of interesting bourbon, or rye whiskey of any sort. If a few stores were treasure troves, most were deserted islands. Driving around Kentucky, I’d have to return to the same few distilleries open to visitors—not that there were many distilleries, period. As late as 2010, fewer than twenty were operating at any meaningful capacity. So while I get misty-eyed at the memory of those shelves stocked with liquid gold, I also know that today we are experiencing a golden age of American whiskey with better access to a wider variety of great whiskey than ever before.

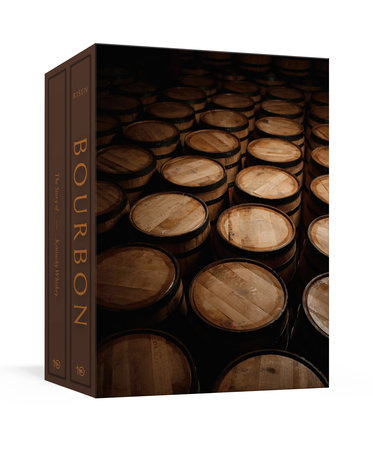

All the distilleries in this book make superb whiskey, and most of them did not exist until quite recently. The same goes for the restaurants, hotels, and bars that serve the millions of tourists who visit Kentucky every year. Hulking black rickhouses full of aging whiskey have always been a familiar sight in the central Kentucky landscape. But these days they are as common as horses. Indeed, bourbon has surpassed horse racing as the state’s signature industry. Between 2015 and 2020, sales of American whiskey (of which Kentucky produces about 75 percent) shot from 20.4 million cases to 28.4 million, a 39.6 percent growth rate, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. For super-premium whiskey, the numbers were even more breathtaking, growing from 1.8 million cases to 4.1 million, or about 122 percent. These numbers, impressive as they may be, are just numbers. The real changes are what all those numbers make possible, which can’t be captured on a spreadsheet. Among distillers, there is a renewed passion for innovation, for building on tradition to create new techniques, new flavors, and even entire new styles. The laboratory at Kentucky’s Independent Stave Company, the world’s largest manufacturer of wooden barrels, conducts hundreds of experiments a year to investigate how different types of oak, new methods for charring, and other nascent technologies can bring out novel nuances in the wood—all of which give distillers a vast toolkit for making layered and intriguing new whiskey.

What keeps innovators, like Independent Stave, going is the insatiable demand from whiskey fans. People who, a decade ago, wouldn’t have touched an American whiskey now wait sleeplessly for news about this year’s release of the Buffalo Trace Antique Collection. And those fans are flooding into Kentucky. In 2014, the Kentucky Distillers Association reported a million visits to its members’ distilleries; four years later that number was up to 1.63 million. And there aren’t just more fans, but also better-informed fans. “People get into questions about mash bills, secondary aging, charring techniques, questions I would never hear fifteen years ago,” Fred Noe, the master distiller at Jim Beam, explained. All these knowledgeable, relentlessly curious whiskey drinkers push distilleries forward, giving the industry the confidence to take risks, such as wine-barrel finishes and single-barrel releases that never would have been tried before.

I have been fortunate to have had a front-row seat during this boom. I first got into whiskey in my twenties, in the early 2000s, when bourbon was still emerging from thirty years of declining sales. But the roots were there; the industry had strong bones. Buffalo Trace and Jim Beam were already selling their single-barrel and small batch bourbons. Willett was bottling world-class whiskey that it sourced from other distilleries. I tried to learn as much as I could, but back then there wasn’t much in the way of course materials to be found—a handful of books and websites, but also a lot of information that was contradictory, unsupported, and just plain wrong. So I decided to do my own reporting. One of the pleasures of being a journalist is that, if you’re lucky, you can get paid to research and write about something you love. And I did. First came magazine and newspaper articles, then books, which turned into speaking, judging, and still more writing opportunities. And I had fun! The people that I met in my travels are some of the best on Earth—kind-hearted, humble, humorous. Especially those in Kentucky, where my father’s people have lived for over two hundred years, mostly in Bourbon County. As a kid living in Nashville, I grew up visiting Kentucky but never really knowing it. Whiskey gave me a reason to return to those roots. My ancestors were farmers, small-town business owners, mothers, and fathers. None made whiskey but I am sure more than a few enjoyed it. This book is dedicated to them.

In 2014, I wrote an article for Fortune magazine about the “billion-dollar bourbon boom.” Toward the end I asked, as a way to insert some drama, when the boom would become a bust. Not if, but when. All these years later, I’m still waiting. I’m not expecting it anytime soon.

Copyright © 2021 by Clay Risen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.