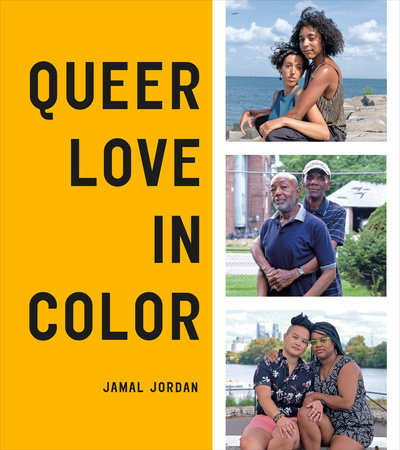

IntroductionThat Could Be Me “I never saw Black queer people as objects of desire,” Aimee tells me. “I never thought that someone would want to love me or someone who looked like me. I thought for a very long time that my only hope in finding companionship was to convince a white person to love me.” She sits before me, her dark skin glowing in a band of sunlight. She wipes away a few tears, as her wife, Denecia, offers a comforting hand. I resist the urge to take a photo.

I traveled tens of thousands of miles across the world to meet queer couples and families of color for this project. Their stories range widely, but one thing kept coming up: the feeling that, on some level, finding love felt impossible. Many people felt invisible, and versions of Aimee’s story were repeated to me, over and over, the wounds seeming just as raw, years later.

“I just felt like I didn’t even exist sometimes,” says Thomas, a young man describ ing his childhood in Detroit. “I didn’t have anything to look up to, to aspire to, to even see. Even today, there’s so few gay Black couples that I can look up to. I think it would’ve been important for me, as a child, to see things that told me:

You exist in this world. You don’t have to hide yourself. You can be authentically, 100 percent yourself and aspire to do what you want and find love and live your life unapologetically and unashamed.” When the world values being white and straight above all else, how do you learn to love yourself when you are neither?

With a superficial look at statistics, an outsider may assume that the core exper ience of being a person who is both queer and of color revolves around struggle. In America, people of color, for example, are less likely to receive mental health care for their traumas than their white counterparts, hold less power across the political spectrum and, with the exception of Asian Americans, earn less money over the course of their lifetimes. Globally, studies consistently find that members of the LGBTQ community suffer from higher rates of substance abuse and mental health issues like depression and anxiety than their straight counterparts. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth are three times as likely to contemplate suicide. That figure jumps to eightfold for trans youth.

It’s clear that we’re hurting.

But the cumulative mental health effects of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation are much too complicated to simply reduce to experiences of pain. The field of research specifically related to LGBTQ people of color is still in its infancy, but sociologists and mental health experts have made tremendous strides in developing a more intersectional understanding of the queer community. In her work, Dr. Kali Cyrus M.D., Professor of Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Medical School (as of this writ ing), challenges researchers to examine another trait unique to queer people of color: Resilience. She notes that queer people of color do not experience higher levels of mental disorders than their white LGBTQ peers. In fact, the research she highlights suggests that queer people of color use their identity as a “source of strength” in ways that cisgenderheterosexual minorities or white LGBTQ people don’t.

In stories about queer people of color, particularly trans people of color, sub jects are often presented as victims. But beneath the surface of those stories are surely further tales of resistance, rebellion, and healing. I started this project with a question: What does feeling invisible do to a person? A community? When I began my interviews, I expected to hear stories of people overcoming their pain and trauma, of the time people spent learning that they are worthy of love. But first, I needed to know: What kinds of traumas do we, as queer people of color specifically, consistently experience?

It is clear that negative impacts start early. I spoke with Dr. Ilan Meyer, a scholar at the Williams Institute for Sexual Orientation Law and Public Policy at the University of California, Los Angeles, and one of the witnesses in the landmark 2013 California federal district court case

Perry v. Schwarzenegger, a challenge to the state’s Proposition 8 law, banning same-sex marriage. He told me that research has shown that “young LGBTQ people have a hard time projecting themselves” as queer people into old age. Whereas most children who identify as straight have ample cultural references to help them form a conception of their romantic futures from a very early age (most assuming that they will grow up to become a married grandmother or grandfather), where are young queer people, particularly children of color, to look for a preview of what adulthood has in store for them?

Younger queer people of color report feeling particularly isolated from their communities. For those of age who are beginning to explore the world on their own, safe physical spaces for queer people, particularly those that cater to com munities of color, are rapidly closing, giving way to digital spaces. And for queer people of color searching for love, friends, or community, this presents its own set of issues. These online spaces, despite their benefits, often make people feel lone lier and less connected, and for a community that disproportionately turns to the internet to find love, those spaces can reinforce the negative messaging that queer people of color experience in the physical world.

Almost 30 percent of LGBTQ couples report meeting their current partner via dating apps. However, as microcosms of society at large, these apps can reiterate a perception that queer people of color have faced, both implicitly and explicitly, for their entire lives:

You have less value. I spoke with Dr. Ryan Wade, a professor of social work at the University of Illinois, about his research into what he has termed “sexual racism.” In his surveys and focus groups of queer men, he finds that people of color consistently report feelings of rejection and objectification—a consistently “dehumanizing” experience, as he describes it—when navigating queer spaces online. But his research reveals so many more questions: What are the longterm effects of being exposed to that kind of messaging? How does it affect psycholog ical measures like selfworth and depression? How does it affect the way that people develop their selfconcept? Their identity? The way they navigate the world?

It will be years before researchers are able to form evidencebased answers to those questions. In the meantime, this book is an attempt to answer one of my own: How do you learn to love yourself and other people like you when every cue in the world tells you it’s impossible?

Copyright © 2021 by Jamal Jordan. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.