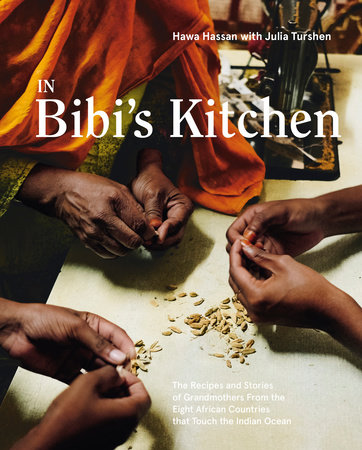

A Bit About the Book These pages hold recipes and stories from the kitchens of bibis (grandmothers) from eight African countries that border the Indian Ocean. Their recipes and stories capture the cultural trade winds and flavors from all those who’ve passed through these countries over the centuries and from the many who remain. In many ways, this is an old-fashioned cookbook that has nothing to do with trends or newness. It’s filled with recipes from grandmothers and their rich histories, which have been handed down through generations. It reflects on times that have passed. Yet in so many ways this is an incredibly modern book that has relied on a web of technology and social connections to come together (including, but not limited to, multiple iPhones, many WhatsApp group chats, dozens of Dropbox folders, and countless text messages). This is a book about connection, about multigenerational connection, cross-cultural connection, wireless connection (!), and, ultimately, human connection.

“Food is . . . just like language. For me, stopping traditions would almost be like throwing my culture away,” Ma Khanyisa, a grandmother from South Africa, told us. She said this from her home in Cape Town over Skype to Hawa, who was interviewing her and recording the interview before sending it over to Julia (more about us, Hawa and Julia, in a moment). Julia transcribed the interview and added it to the manuscript for the book you’re holding, taking note of that line, feeling it to be the crux of this book. Later that week, Khadija M. Farah (more about her soon, too) photographed Ma Khanyisa at her home in South Africa, making corn porridge with a mixture of wild greens known as imifino (check out the recipe on page 211). Khadija also used her phone to film Ma Khanyisa cooking the dish, at times holding her phone in one hand and her camera in the other. She sent the videos to Julia, who wrote the recipe for imifino by watching the videos and then writing down each step that Ma Khanyisa had taken. (Julia has spent over a decade writing cookbooks and can eyeball a tablespoon from a mile away.) There was lots of rewinding to make sure no part of the process had been missed. Then Julia and Hawa tested the written recipes in their own homes to make sure the dishes would translate to Western kitchens.

Variations of this process were repeated for all the grandmothers you’re about to meet in these pages. Many live in the eight countries we cover, some left their homes in difficult times and now live in the United States, while Ma Sahra (see page 69) lives in the same place she was born, but because the border has since shifted, her birthplace, once part of Somalia, is now recognized as Kenya. This complicated content-gathering was at times confusing (and at times frustrating when files got stuck in the “cloud” somewhere between continents), but during the entire time, we were all driven to keep speaking this language of food and to make sure traditions and cultures were honored.

In Bibi’s Kitchen is not about what is new and next. It’s about sustaining a cultural legacy and seeing how food and recipes keep cultures intact, whether those cultures stay in the same place or are displaced. By celebrating bibis and their cooking, we aim to use food as a way to honor the matriarchs of numerous families and countries. And this isn’t just any old book with fun ideas of what to make for dinner (though you should make the recipes—they’re great!). It’s also a collection of stories about war, loss, migration, refuge, and sanctuary. It’s a book about families and their connections to home.

This book fills a deep and vast void in the contemporary cookbook market. There are barely any cookbooks published by American publishing houses that feature African food, let alone food from one of the many parts of that continent (disturbingly, Africa is often mistaken as a country, not a continent). On top of that, so many cookbooks are written and photographed by authors and photographers who are not from the places featured in cookbooks and who are unable to bring the richness and complexities of those cultures to the page. On top of that, few cookbooks, or any books, for that matter, champion women who have lived long enough to have grandchildren. We are so happy to tell the stories of these bibis.

And the eight countries we focus on? Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Madagascar, and Comoros—they all touch the Indian Ocean, some just on an eastern edge, while others are completely surrounded by water (Madagascar and Comoros are islands just east of Mozambique). That they all have the Indian Ocean in common means that they’re eight countries bound by trade, by veritable waves of commerce.

Most notably, these eight countries define the backbone of the spice trade, many of them exporters of essential ingredients like pepper and vanilla. We can understand their economic histories, as it were, by learning about their recipes. As interest in “global flavors” continues to gain momentum, it’s important to do the work of understanding the culture and people behind those flavors and what they’ve been through. It’s important to understand how these foods have traveled and evolved from small regions across distant oceans to kitchens as far away as ours in New York.

These eight countries also tell a range of stories, and in sharing the bibis’ most favorite recipes, we also learn of the lasting effects of colonialism, even in countries that have maintained independence for decades. The late author Laurie Colwin once wrote, “If you want to know what real life used to be like, meaning domestic life, there isn’t anywhere you can go that gives you a better idea than a cookbook.” Examining a country’s best-known dishes tells us about so much more than just its popular flavors. It tells you about that country’s geography and climate, about farming and distribution, and about those who live there and what their day-to-day life might look and taste like. It also tells you a lot about who holds power and influence.

Copyright © 2020 by Hawa Hassan with Julia Turshen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.