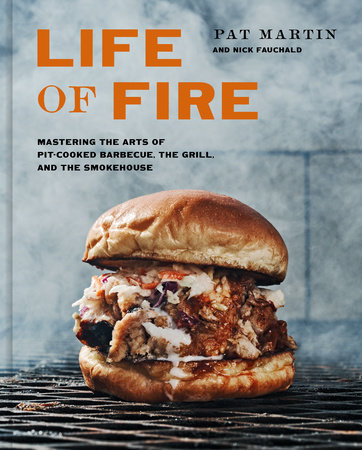

MY STORY This book is a guide, pretty much everything I know, about the craft of barbecue and cooking with fire. Now, with barbecue, people are beyond opinionated. Folks love to talk about regional styles—the differences in vinegar versus tomato versus mustard based-sauces, the cuts and types of meat used in this corner of the world versus that one. The style I’m most connected to is the old, and dwindling, greatly overlooked but beautiful art of West Tennessee whole hog. I love cooking—and showing people how to cook—ribs, chicken, shoulders, hams, vegetables, sides, and more, but the art of pit cooking whole hog is not just the summit for me; it’s my roots.

But I didn’t learn all this from being born into some barbecue family, the stereotypical story of a boy knee-high to his daddy and following him around a pit house all of his life only to take the reins one day. Instead, I learned to cook barbecue through a few twists of fate, some epiphanies, a pitmaster mentor, a lot of experimentation and even more stubbornness, and more hours than I can count of staring at, listening to, smelling, feeling, and handling fire. This path started for me in high school, thirty-five years ago, and I’m still on it. And in my world, whether you want to go all-out and cook a whole hog (and I hope you do one day), or just grill up some supper, it’s all about learning how to work with fire. I feel like it’s my responsibility to share what I’ve learned about how to cook all through the life cycle of a fire—from what to char over a fresh, young fire; to open pit cooking with the powerful but controlled heat of a more mature fire; all the way to cold-smoking hams, bacon, and sausage with the fading embers of the winter fire. And in there, in the middle of that life of fire, is what I do with all my heart: barbecue.

My story begins as most do, with my family and its roots. You can’t know me without knowing that backstory. Both sides of my family are from the same small town in northeast Mississippi: Corinth, sixtyfive miles east of Memphis, Tennessee. I was born in Memphis, at the old Baptist hospital—the one Elvis was pronounced dead in.

My mom grew up in town. Her dad, my Pa-King, was a grocery rep for all of the little country stores in and around northeast Mississippi, and her mom, my Mi-Mi, worked for the railroad in Corinth. My dad had grown up dirt poor on a farm in Corinth, in a typical farming family growing or raising most of the food my grandmother cooked. His dad, my Paw-Paw, was a small farmer his whole life and his mom, my Maw-Maw, worked as a bank teller at the old Bank of Mississippi. Dad attended Mississippi State on a basketball scholarship, majored in economics and business finance, and eventually moved us up north, becoming a legendary trader on The Street, which is what they all called Wall Street. He was literally the poor country boy who made it in the big city.

Early on, our move to Connecticut was great. There was a seemingly endless supply of woods and waters to swim in, with no cottonmouths to have to check the pond banks for before you jumped in like we’d have to do in Mississippi. Our church was a mainstay for our family, and most of the folks who went to church with us were also from the South, so it was both a place of worship and a cultural center. A lot of Sundays, Mom and several other women would preside over a table of fried chicken, cornbread, purple hull peas, creamed corn, and so on and so forth.

But as I started getting on up in school, life changed. Because of my ADHD, I was always making bad grades. And I started getting in trouble, a lot of trouble, and got suspended from—or kicked out of—one school after another. I remember, around fourth grade, being made fun of by some boys who were pretty big bastards for grade school. They came at me with all of the typical clichés about folks from the South: Can your parents read and write? Is there even running water in Mississippi or do you use outhouses? I’d get mad and fight back, end up getting roughed up, only to do it all again a few days later.

But then one day in fifth grade, something happened that left an impression far longer than an ass whipping from some overgrown kid on the bus. My teacher, Mrs. Pateraki, announced that we would have “Where Are You From?” days, where the kids in the class took turns sharing food, music, and culture from their families’ heritage; we had Italian food, Puerto Rican food, Irish food, and so on. When it was my turn to present my family’s story, I was pretty excited!

Mom got up early that morning and made a bunch of fried chicken tenders and biscuits for the class. I brought my tape recorder and a cassette of the Southern comedian Jerry Clower’s greatest hits. I remember having my presentation ready. I was going to talk about my grandfather as a farmer, the battles of Shiloh and Corinth, William Faulkner and Hal Phillips . . . .

As my classmates were eating their chicken and biscuits and awkwardly laughing to Jerry’s jokes, my teacher walked up visibly annoyed, hit the stop button on the tape player, and asked me, loud enough for the entire class to hear:

“Patrick, this is nice and all, your family’s from Mississippi . . . but where are they really from?”

“From Mississippi,” I answered, not really understanding her question at all.

“But what about before that?”

“I don’t know what you mean. . . . There is no ‘before that.’”

“Before your family came to America.”

I didn’t know how to answer that! I had never thought of that in my life, ever. I didn’t know how to process what she was asking me. It confused me, but what it really did was embarrass the piss out of me. She basically communicated to me and the class that our family story and its roots didn’t matter because I couldn’t pinpoint some Celtic settlement over in Ireland or somewhere that is the origin of the Martin name. The class was silent and staring at me. It was a terrible feeling, and I can feel it now as I type this. I wanted to run out of the room. So she impatiently thanked me and asked me to sit down, not even allowing me to share the rest of my presentation except for Mom’s fried chicken. Trying not to cry, I just sat there at my desk while the next kid was called up. I was so proud and excited to share of my roots, and instead was made to feel embarrassed. I was so hurt, and pissed.

Shortly after school would let out for the summer, my parents would send me down to Corinth to be with my grandparents for a while. When I would get there, they’d meet me at the gate at Memphis airport and we’d usually grab a barbecue sandwich before driving the sixty-five miles back to Corinth. Things would immediately start to feel normal. My Maw-Maw would get up in the morning, make us breakfast (always with fresh biscuits from scratch), and go to work at the bank. My Paw-Paw would be somewhere out across the highway 72 in the rows of soybeans, milo, or whatever. Families in that area don’t leave, generations stay on or around—much like old villages in Europe my teacher wanted me to identify with. I started to become friends with a lot of kids there; almost all of these kids’ parents went to school with my dad, or my aunt and uncles, and our friendships were very easy and fluid.

On weekends, our whole family would get together— uncles, aunts, cousins, the whole lot. On Saturdays, the men would fire up the grill. I was right there, watching in awe of them. Everything they did was with intent, and a lot of times the “hard way.” They changed their own oil a certain way, shined their shoes a certain way, shaved a certain way, started fires a certain way. I’ll never forget the first time Dad asked me to fill up the chimney starter with charcoal, stuff the bottom with newspaper, and light the grill. It was a big deal for me, like he invited me into the world of being a dadgum man.

We only really used the grill for burgers or steaks. That was fine by me, since I didn’t know anything different and really, it was more about the feeling of being around the fire and family that mattered to me. When I was fourteen or fifteen, I saw a book in the book store called

Thrill of the Grill by Chris Schlesinger and John Willoughby. I bought it, and it became my culinary bible for years. It was the first time my mind was open to cooking anything over fire, not just the red meat usual suspects. One part, in particular, grabbed me: a story that Chris wrote about cooking a whole hog with his dad when he was young. I thought that was cool and wanted to do that one day. Little did I know that an entire culture of whole-hog barbecue was just forty-five minutes up the road from Corinth. And little did I know it would find me in just a few short years.

Copyright © 2022 by Pat Martin and Nick Fauchald. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.