IntroductionI’m local: L-O-C-A-L!

As brown as one dollar size ‘opihi shell

I’m as local as the ume in your musubi

As one spaghetti plate lunch with side order kim chee

I’m as local as the gravy on the three scoop rice

As all the rainbow colors on da kine shave ice

—Frank De Lima’s Joke Book

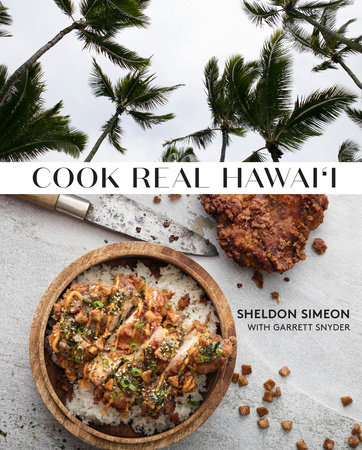

What is the food of Hawai‘i? Ho boy, that’s one question I’ve been asked many times. I always have an answer, but every time it leaves my mouth I wonder if I captured the whole truth, in all its splendor and complexity.

Hawai‘i has been home my entire life. I’m sure many people say this about where they grew up, but I believe there’s no place on earth more beautiful than our islands, home to swaying palm trees, sugary white sand beaches, and impossibly green mountains streaked with waterfalls. The Hawaiian Islands form one of the most visited yet most remote archipelagos on earth, a tiny scattering of green surrounded by the blue vastness of the Pacific. We’re the fiftieth state, but, as we joked in school, the guy who drew the map always stuck us way in the corner. About 1.5 million people live in Hawai‘i, a number dwarfed by the 10 million who came as visitors last year. How does a place that has so long been defined by the outside world define itself? The answer is the reason why I set out to write this book.

After competing on two seasons of

Top Chef, I’ve been extraordinarily fortunate to have a kind of national exposure. When I was younger, I saw these opportunities as a way to gain recognition and validation from the mainland, looking to restaurants in L.A. and New York for inspiration.

During my first season on the show, most people knew me as the chill Hawaiian guy. It took me a while to get across that I was not actually Hawaiian—as in native Hawaiian—but a third-generation Filipino from Hawai‘i. Big difference. See, in Hawai‘i we identify ourselves ethnically rather than geographically, which may tell you something about our cultural influences. On the mainland people might say “I’m a New Yorker,” but here it’s “Betty is second-gen Japanese Korean,” or “Lyndon? He’s Portuguese Chinese Hawaiian,” and so on. More on that later. The Hawai‘i-Hawaiian thing was the tip of the iceberg, though. On the show I found myself answering lots of questions about where I was from.

Do you eat lots of Spam? Yes.

Pineapple? Sometimes.

Macadamia nuts? Not as much as you think.

Is the poke really better there? Yes, by a huge margin.

Do you drink mai tais? Sure, but I like beer and Crown Royal better.

I came to realize that the Hawai‘i I knew was often misunderstood on the mainland, shaped by years of ad campaigns with airline stewardesses handing out leis, ham and pineapple pizza, and big brown guys dancing with fire sticks. I mean, those do exist, but they’re not the whole picture.

The warmth of home, what I missed most when I was away, was in things that guidebooks didn’t explain to tourists, the deeper nuances that make our culture different from any other place on earth. Most of all that meant food. Hawai‘i food, or what we call local food, tells a story of where we come from. It is embedded in every part of our language, our songs, our jokes. We celebrate it every chance we get. It doesn’t just fill our bellies, it keeps us being who we are. If you didn’t know the Hawai‘i I knew, how could I share all of that with you in a plate of food?

For the last many years, that question has defined what I cook. It’s not just about

ono grinds (delicious food), it’s about connecting what we love to eat with culture and community. A deeper meaning to the deliciousness, if you will. Eventually that pursuit led me to the cookbook that is in front of you. What better way to tell a story?

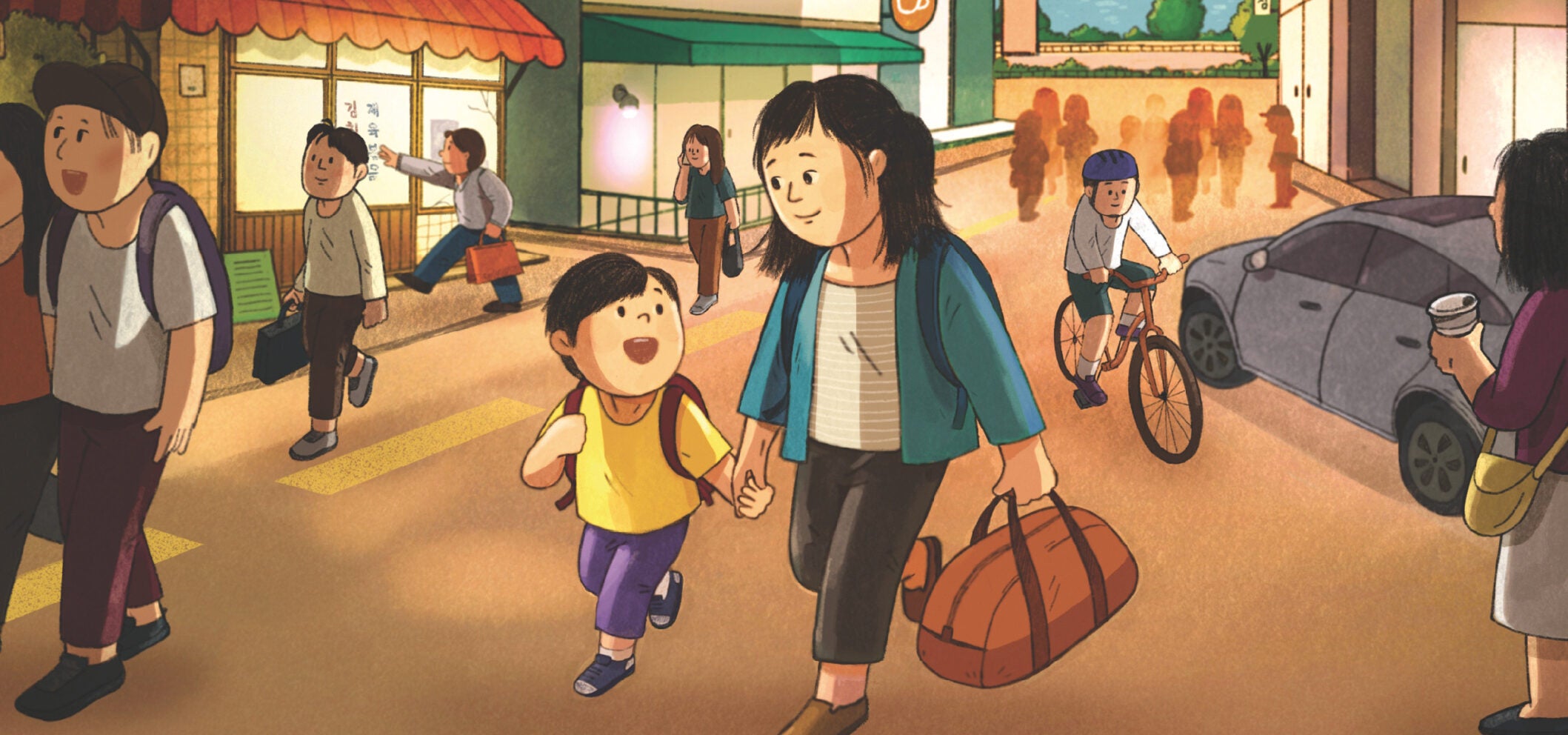

Before digging into local grinds, it’s necessary to understand one concept that underpins the entire culture of Hawai‘i. Aloha is a word you’ve no doubt seen plastered on coffee mugs and T-shirts at gift shops. You might even know it means both hello and goodbye. But the true meaning of the aloha spirit is something more profound: the extension of goodwill and grace with no expectation of reward, the purest expression of compassion, hospitality, and love. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the concept of aloha originated in one of the most isolated places on earth, where by necessity people took care of each other and the land that fed them in order to survive. Aloha is demonstrated not just in words but in deeds, and the creating and giving of food for friends and strangers alike is one of the most essential acts of aloha in existence. Food makes family, families make food. There is no one without the other.

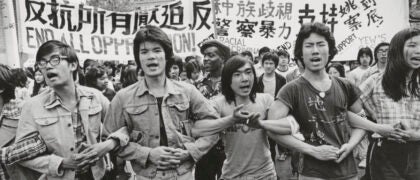

The family we talk about in Hawai‘i can mean different things, as in your blood relatives but also your distant cousins, adopted relatives, in-laws, friends, and even neighbors, all encompassed in the Hawaiian word

‘ohana. This notion of one big ‘ohana suits the diversity found here, too, made up of a hodgepodge of cultures that arrived as immigrants from countries like China, Japan, Portugal, Korea, and the Philippines. You may have heard Hawai‘i referred to as “the melting pot of the Pacific,” but that’s not entirely accurate, since it implies everything blended together into one homogenous stew. The reality is that Hawai‘i is more of a salad bowl, or better yet a plate of chop suey: each ethnicity tossed together but still distinct. Growing up, we poked fun at each other’s differences and quirks in a good-natured way, while also being aware and proud of those unique traits that made us who we are.

For a sociologist, this intermingling is fascinating. For a cook, it’s delicious. Peek into a garage or house party on the weekend and count the number of cultures spread out on the table. Oxtail soup nestled next to kim chee dip with a side of fried wontons and fish cakes. Across the room the kids are fighting over the last piece of butter mochi. From afar this multicultural combination seems to have no rhyme or reason, but to us it just feels natural—the most organic form of fusion cuisine. It’s a rich and intricate history playing out on the table. I’m not Korean, but I love to make kalbi. I’m not Chinese, but I love to make chow fun. Breaking bread together expanded our palates and created new combinations of flavors and ingredients. All those traditions running into each other is what makes our food so special. As locals say,

how lucky we live Hawai‘i.

Copyright © 2021 by Sheldon Simeon with Garrett Snyder. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.