Introduction

When you think of marble you probably think of it in its most basic, everyday forms: as a countertop, a kitchen backsplash, or a floor if you frequent slightly more luxe apartments. It’s a material that’s considered opulent but also recedes into the background. Even at the Taj Mahal, it’s not the marble itself that people marvel at; it’s the way it’s carved and inlaid—and the fact that there’s just so much of it. Marble is luxurious but it’s also durable; as much at home in a cathedral or a palace as it is in a hardware catalog. In other words: marble is nothing special.

But the California Crystal Cave in Sequoia National Park, a living structure of marble and calcite, will make you feel like an alien on your own planet. As I stood outside the cave on a midsummer day, looking at the spiderwebbed gate that led to the cavern’s tunnels, I felt a breeze thirty degrees cooler emanate from the entrance, touching my cheek like a ghost beckoning me inside. My partner, Matt, and I were there for a discovery tour, conducted only with flashlights. Over the course of a million years, water had been inching its way across a solid piece of marble inside a mountain, dissolving it bit by bit, sculpting entire rooms in its wake. It’s a magnificent natural structure; the supernatural need not apply.

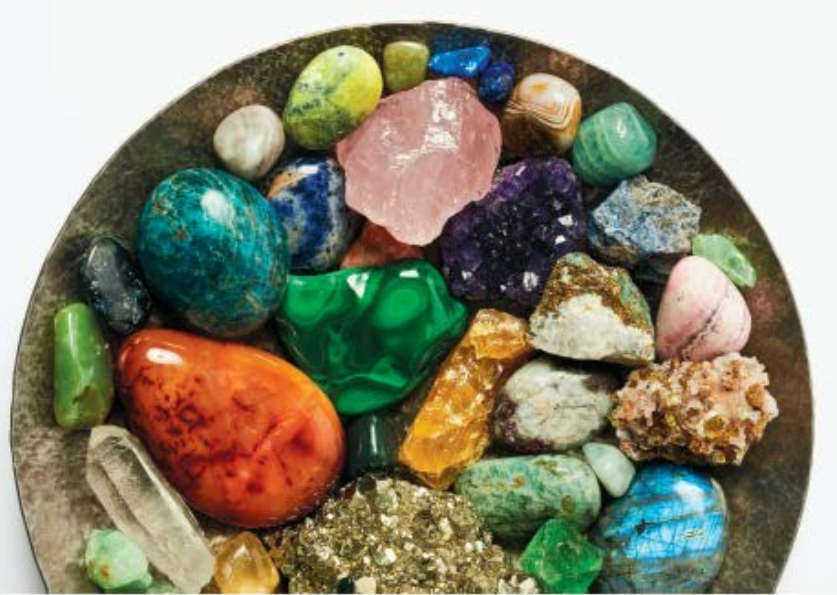

I was never interested in crystals in a metaphysical or spiritual way. I was always drawn to their reality—their solidity. In a childhood diary, I bragged about my rock collection; pyrite, marble, raw emerald, and smoky quartz that I kept in a seashell-decorated, heart-shaped box. I opened it every night, removing each one by one to admire them, and then puzzling them all back so the lid could shut. In 1992, when I was six years old, I had sixty-two specimens, and big books with big pictures telling me where the rocks were likely mined, and what their practical uses were. Quartz was used in making computers, diamond to cut hard metals, crushed pearls to lend makeup an iridescent quality. In my diary I recorded which were my favorites—one day hematite, another limestone. I liked the way they glittered, the way they felt, how some seemed too light for their size and others too heavy, some sharp and some waxy, and how there could be such variance to what were essentially condensed forms of dirt. These stones didn’t need to have otherworldly properties in order to be valuable. They were fascinating on their own.

Inside the Crystal Cave, there are marble formations that look like a snowdrift, like popcorn or organ pipes. There are white calcite formations that look like the folds of a human brain. There are basins full of clear water called “Fairy Pools” that show a calcite lattice, like the most sturdy and elegant caul fat, beneath its undisturbed surface. Marble reaches out like the mangled claws of spirits trying to escape a dark prison. You could watch your breath becoming vapor in the path of a flashlight. I felt as close to magic as I’ve ever been.

At one point we were asked by our guide, Michelle, to sit in the dark in total silence and listen to the sounds of the cave—water dropping, echoing, some sense of coolness and space the silence only amplified. It seemed natural that people who stumbled into this formation before flashlights and paved trails wanted to take this energy with them, to have a physical remnant to connect them back to this massive formation. Perhaps when they saw the calcite chip stolen from the cavern wall, no matter how out of context, they would remember how it felt to be wholly absorbed by the earth. In the darkness, any theoretical power of the stones around me became immediately obvious.

“Nature” has come to mean something very specific in mainstream understanding, namely, something to save. It’s dying, after all, and we’re the ones killing it. Animals are becoming extinct, coral reefs are drying up, the seas are increasingly inhospitable, and the forests are being cut down. Even without human intervention, these forms of nature change all the time. Animals eat each other, trees dry out and rebloom, rivers push into new courses. But a rock, a mountain, is dark and craggy and rough, ready to kill you. It used to be that mountains inspired terror instead of admiration, back whe nature was something to prepare against, not something to consume. You could die on a mountain (people still die on mountains), but even if you didn’t, you would die anyway, and the mountain would remain. These formations are not changing at a scale a human can understand.

Crystals are nature. Crystals—the shiny, multicolored gems and crystalline structures we speak of here—are born of pressure in the earth and die by eventual erosion. “In a crystal we have clear evidence of the existence of a formative life principle, and though we cannot understand the life of a crystal, it is nonetheless a living being,” wrote Nikola Tesla in his essay “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy,” published in 1900. Crystals are not permanent, but they live outside of human time. Rocks, supposedly, are doing fine without us. Which is exactly why we want them.

Copyright © 2020 by Jaya Saxena. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.