ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES

A flash of harmless lightning,

a mist of rainbow dyes.

The burnished sunbeams

brightening.

From flower to flower he flies.

— JOHN BANISTER TABB

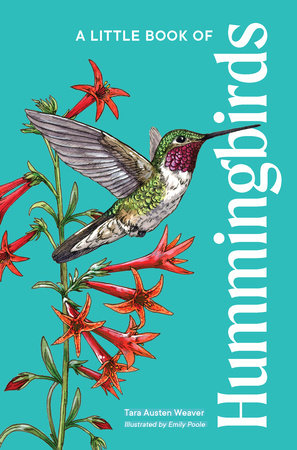

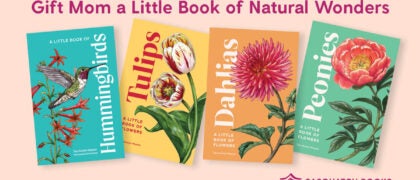

It’s that flicker of glinting color—sometimes no more than a tiny rapid wingbeat disturbing the air—that tells us a hummingbird is nearby. These iridescent wonders delight all those lucky enough to view them. From the smallest Bee hummingbird of Cuba, weighing in at less than 2 grams, to the Giant hummingbird of the Andes, which weighs ten times as much, these small, colorful birds have captured our attention like few others. It’s no surprise that Spanish explorers, the first Europeans we know of to see these very American birds, referred to them as

joyas voladoras—flying jewels.

Hummingbirds are a contradiction. How can such small, delicate creatures migrate from Mexico to Alaska? They have the fastest metabolic rate of any warm- blooded animal but can slow down their system to enter a type of hibernation when needed. Their wings move not up and down, but in figure eights, enabling them to navigate in any direction.

Found only in the Americas, the history of hum- mingbirds is not fully known—their small, hollow bones decompose too quickly to have left a significant collec- tion of fossils. One of the few known fossil specimens was discovered in 1994 in southeastern Germany, giving rise to theories that hummingbirds originated in Eurasia, migrated to the Americas, then died off in their native lands. Scientists estimate that hummingbirds split from the swifts, their closest avian relations, about 42 million years ago.

Hummingbirds may not have much of a fossil history, but there is a rich cultural history to these fascinating birds. They play a role in oral traditions, folklore, and crafts throughout the Americas.

The Hopi and Zuni people of the southwestern United States credit the hummingbird with bringing much- needed rain from the gods to the people. A traditional tale from Puerto Rico tells the story of a boy and a girl who fall in love. Because their rival tribes do not approve of the union, the girl transforms herself into a red flower who is visited regularly by the boy, now in the form of a hummingbird. In Northern California, the Ohlone tell the story of how the hummingbird stole fire from the badgers and gave it to the people. The red- feathered throat of the hummingbird is due to a piece of coal that fell and permanently marked the bird with the color of flames. These are just a few examples of numerous hummingbird origin stories.

Though small in stature, hummingbirds were known as symbols of strength in cultures throughout the Americas. In southern Peru, the Nazca people etched a massive hummingbird figure into the red desert. Dating as far back as 200 BC, the figure is over a thousand feet long—about equal to the height of the Empire State Building in New York. Some of the figures that the Nazca drew are so large and can only be fully seen from the air. As a result, the designs did not become apparent to modern humans until the adoption of air travel in the 1920s. The significance of these giant figures is unclear, but anthropologists assume some spiritual connection due to the existence of nearby grave sites.

Starting in the early 1300s, the Mexica people in what is now southern Mexico worshipped the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli, who was known as the Left-handed Hummingbird; it was said that fallen warriors in his army would be transformed into hummingbirds. The Taino people of the Caribbean, who believed hum- mingbirds were symbols of rebirth, called their young men Hummingbird Warriors. This, unfortunately, did not protect them from the violence brought in 1492 by Christopher Columbus and other European explorers, who wiped out as many as three million Taino by the early 1500s. These European explorers also brought news of the hummingbird back to Europe, spreading their popularity but endangering their numbers.

European thirst for empire was on the rise, and a number of curios were being brought back from far corners of the globe to fill “curiosity cabinets” being assembled by scientists and aristocrats across the continent. One such collector was John Gould, who became the most celebrated ornithologist and bird artist of Victorian-era Britain. He helped Charles Darwin develop his theory of natural selection (Gould’s work on finches is referenced in

On the Origin of Species, Darwin’s seminal work on evolutionary biology). Gould was also a great fancier of hummingbirds.

Gould’s hummingbird collection was vast—more than three hundred species. This assembly allowed him to complete what is considered his masterpiece:

A Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Family of Humming- birds, the first volume published in 1849. Twelve years in the making, the monograph includes 360 illustration plates, many decorated with gold and silver leaf to evoke the shimmering nature of hummingbird feathers.

Gould played a big part in popularizing the humming- bird in Europe. His collection was exhibited in 1851 as part of the Great Exhibition in London, which drew more than seventy-five thousand visitors. Among them was Queen Victoria, who later wrote in her journal, “It is impossible to imagine anything so lovely as these little Humming Birds.”

This exhibit sparked a craze for hummingbirds in Europe—as an item of decoration and trade. “Their minute size and gemlike appearance caused them to be coveted as jewelry and adornment for women’s hats,” writes Alexander F. Skutch in his book

The Life of the Hummingbird. He reports that a single dealer in London, over the course of a year, purchased more than four hundred thousand hummingbird skins.

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that organizations such as the Audubon Society and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds shifted the focus on hummingbirds from consumption to conservation, promoting an ethos of appreciation and protection of these unique and flamboyant creatures in the wild.

Copyright © 2024 by Weaver, Tara Austen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.