IntroductionDear Reader,

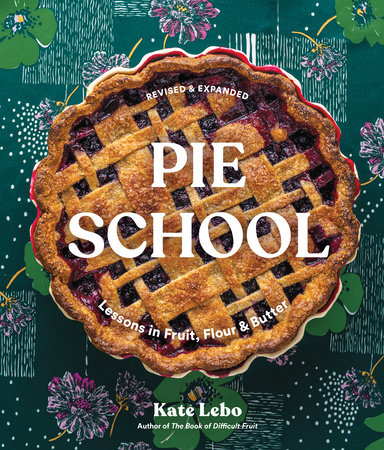

When I started writing the first edition of

Pie School, I lived alone in a duplex in Seattle, one of ten squat buildings I’d heard were built to house last century’s cannery men. After I lived there, I repeated this apocrypha as if it were fact. It gave me a sense of history. It helped me imagine a place within that history. Or at least within the rumor of that history. It was six years since I’d made my first piecrust, five years after the subprime mortgage crisis began, one year since I’d founded the Pie & Whiskey reading series with my then-friend Sam Ligon, five years before I’d marry him, and seven before the COVID pandemic canceled all parties and forced us to cook most of our meals at home.

It was 2013, and my kitchen was at the center of my apartment. To leave the bedroom and walk into the living room, I had to pass through the kitchen. To leave the house at all, I had to pass through the kitchen. The kitchen was narrow as a hallway, with ancient appliances and scuffed wood floors that reminded me I was one of many residents who’d worn the same route through this place. The oven was electric, ancient, unreliable. A lump of lard crust once fell to the hot oven floor and lit there, and would not go out. I watched the flame as if it were a candle, then scooped the char into an aluminum pie pan and tossed it into the rain. Still, that oven baked twenty-four pies a day when I needed it to—a huge number for someone who had no culinary training, who’d never worked in a bakery, who was baking in a shoebox.

That oven and I, we got to know each other. I knew when to over-or under-turn the temperature dials, when to shift pies so they wouldn’t scorch, when I could walk away and when I needed to hover. I’d been learning how to bake pie the hard way (through ugly but edible mistakes) and the easy way (through reading cookbooks and looking for mentors). Online, I found a network of people who called themselves pie ladies. I began hosting pie sales at home.

That was the year my reputation as a pie baker began to cohere around a series of classes I called Pie School. When Gary Luke from Sasquatch Books emailed to ask if I’d ever considered writing a cookbook, I was shocked. I knew how to write, but not how to write real recipes. Given the chance to imagine what kind of book I might propose, I kept thinking of the cookbooks I didn’t like: the ones that reinforced a consumerist, photoshopped domesticity. I can’t tell you now what those cookbooks were. I doubt there was a particular one. Really what I was imagining was the person and cook I wanted to be; as I imagined, I measured that future woman against what I did

not want to be, but perhaps couldn’t help sort of being, considering how much I enjoyed key elements of traditional domesticity. I hoped I could write a book that would soothe that unease. A book that celebrated pie but didn’t ignore issues around food in general—and this crown jewel of Americana in particular.

That pie

lady thing, for example: an honorific that gives its bearer a kind of folk status, but excludes piemakers who don’t consider themselves ladies. Sexism’s consolation prize for women was once the home kitchen, which makes going back into that kitchen complicated for everyone. I kept thinking about M.F.K. Fisher’s description of her grandmother in “The Measure of My Powers.” In this short essay, it’s 1913 or so. Grandmother forbids all help while stirring a vat of molten strawberry jam. She cuts an awesome, priestess-like figure through the sweet steam; the gray foam on her wooden spoon is the first thing Mary Frances ever tasted that she remembers wanting to taste again. In this kitchen, with this fruit, Grandmother is intimidating and in control. Unsaid in the essay—but palpable anyway—is the fact that the moment she walks out of the kitchen, she loses that power. She can’t even vote.

Then there’s the way pie can be considered a symbol of nostalgic white America, even though wrapping dough around filling is in no way limited to European or European-descended cultures, and even though many of the best American pies are rooted in Black cuisine. These truths don’t cancel each other out. Pie can be critiqued as nationalist shorthand. Pie also evolves with what it means to be American and invites all to the table. Pie is small and boring and predictable. Pie is big and innovative and delicious.

All things considered, my main motivation when opening a cookbook is to learn how to cook, not to become the unwilling recipient of a political screed. How could I put pie in a more complex context while also (and mainly) keep the promise every pie cookbook makes—that I’m going to teach the reader how to make the best pie they’ve ever had?

I was still untangling all these snarls when I went to my first meeting with Gary and told him I wasn’t going to write some sweet little book about pie. What sort of book

was I going to write, he asked. I didn’t know yet. It could be a kind of manifesto, a tart book about sweet things. In May 2013, I was still stuck on what sort of book I was writing when I encountered an entirely different sort of snarl: I lost my apartment.

My loss wasn’t special, and it wasn’t uncommon. A new landlord had bought my duplex and jacked the rent, that’s all. This seemed important—ironic, at least!—because I was writing a

pie cookbook. That queen of domestic treats. The dessert that, once mastered, signaled a certain kind of dominion over the kitchen. I’d been thinking about how to make pie-making accessible in terms of skills I could write about—how to handle the dough, select fruit, fiddle with your oven, all that stuff. I’d taken for granted that readers would have a place to bake. That they’d have homes. I’d assumed

I would have a home. And I still had forty recipes to write.

For the rest of that year and all of 2014, I lived with my parents, with friends, in the homes of acquaintances who needed house sitters, and in a rotting but splendid trailer my family owned in the woods near Mount St. Helens. As I baked and wrote, I began to understand that making pie accessible wasn’t just about the way we pass down skills or write recipes. It’s also the consistency and safety of our homes, the backdrop that allows a person to relax and learn.

It’s the summer of 2022 now, and soaring Seattle rents are an old story. One that’s being told anew in places across the country that never had this sort of problem before—places like Spokane, where I now live. It’s a story that’s important to pie because, in the years since writing

Pie School, I’ve come to think of pie as a food that emerges from the cycles and seasonal rhythms of a well-known kitchen. Pie is a food that helps plant the baker in their kitchen. It wants the baker to take root.

Obviously, we don’t need to be settled in our own homes to make pie. The first edition of this book was written while I was rootless, and I can personally attest to the quality of dough rolled on a conference table with a bottle of wine, then baked in a toaster oven. Our cuisines develop in response to our environments, our living conditions, what’s easy to find, what’s affordable, what weather and culture and activity make us crave. The kind of pie I make is a settled food, but if you aren’t settled, don’t let that stop you from baking. Pie is flexible. If you own your dream kitchen, you can make pie. If you’re borrowing time in a cramped galley, you can make pie. Delicious pastry can’t resolve the larger questions of anyone’s life, but it can answer a few of life’s daily problems—like what’s for dinner and what’s for dessert. Sometimes that’s the best we can ask for. Sometimes that’s all we need.

I write you now after spending the last two years in the forced hibernation of a quarantine that was punctuated by great social change, constant culture war, wildfires and heat domes and one-hundred-year floods, plus the mind-splitting joy of bringing my son, Cy, into the world. What’s a pie cookbook for when we’re afraid of our fellow citizens, concerned for the future of democracy, and feeling the heat of a warming climate? I can offer this version of an answer: pie gets more useful the smaller I make it. I don’t mean that literally. My pies still serve eight—or six or ten! I mean that what pie is for in my life has narrowed and that as it has narrowed, it has deepened. In my mid-twenties and early thirties, pie was a way to transform my life. It was a brand. It was something simple I made on repeat until my relationships, my home, and my understanding of cooking became a practice that no longer felt like it could be ripped from a glossy magazine or trademarked by a hashtag. Today, pie is what I bake when I want something a little special for family dinner on Tuesday night, but not so special that making the meal wears me out. Pie is my job; revising this cookbook is how I’m able to stay at home and be with my son while working. During the COVID pandemic, pie is what I brought my neighbor when her kids were in Zoom-induced despair, or what I gave my other neighbor when he was dying of cancer. He didn’t even eat it—his caregivers did. But that’s not the point. The point is that small tie. That little gesture that isn’t everything, but is something, and matters.

This is still a book for beginners. Now it also presents a way to deepen your baking practice through turning your attention to ingredients. Not just how to source the best, but how to look beyond the grocery store toward what’s fun to gather or plant, and what deepens the cycles of your kitchen and your relationship to the place you live. I don’t mean to imply that you must render your own lard or mill your own pumpkin puree or find the freshest whole grain flour. But if that’s your idea of fun, this book can help you do it.

You still won’t find cream or chocolate pies in these pages. And you still won’t find the food processor—though I have embraced a few culinary gadgets since 2013, namely the mandoline and the mortar and pestle. You

will find recipes for whole grain piecrusts that, thanks to landrace and heritage grains, rival traditional white flour piecrusts for flavor and texture. I’ve added two new chapters too. The first new chapter collects some of the savory pies I began making when Cy joined us, plus advice on how to improvise vegetable pies with the contents of your produce drawer. The second new chapter takes inspiration from my 2021 collection of essays,

The Book of Difficult Fruit, to explore the potential of pies made with native and lesser-known fruits. All the recipes I’ve added are rooted in my changing family—with a baby in the house, making dinner takes priority over making dessert—and the mentorship I’ve received from Lora Lea Misterly of Quillisascut Farm, who, among many things, has taught me to adopt a “why not?” approach to cooking, take inspiration from the produce I buy locally, plant what I can in my own yard, and waste as little as possible. These new recipes will have a different texture than my older recipes. I hope their differences will feel like layers in time.

Pie School is back in session. If you’re new to class, welcome. If you’re a return student, welcome back.

Now let’s go wash our hands.

Yours in flour and butter,

Kate

Copyright © 2023 by Lebo, Kate. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.