Introduction

Growing up in my family’s Chinese restaurant and then becoming a professional food writer did not give me license to write a cookbook. I had the ingredients, so to speak: an immigrant story, restaurant credibility, a journalism degree, a food column in the

Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper, a fan base, an agent, even polite interest from a couple of New York publishers. But I had nothing to say.

It wasn’t until after I had gotten married, had two children, quit the newspaper, and changed career paths a couple of times that the cookbook declared to me its need to exist. Life had taken me on the scenic route toward this end, and it began with the Chinese Soul Food blog in 2007, which I had started in hopes of maintaining my weekly practice of writing and providing a hub for my fans. I also wanted to create a space to share straightforward but comforting recipes inspired by foods I ate growing up. The ingredients wouldn’t break the bank, and the recipes could be made, possibly, with a small child literally wrapped around your leg or while wearing a baby in a sling. That scenario was a reality for me at the time. Money was tight too, so I had to be resourceful about ingredients. I knew that the Chinese cooking I had grown up eating could be extremely economical, considering many stir-fries are vegetable-centric with meat only as a condiment. I figured if I needed such a resource, there probably were other parents out there in the same boat. Despite a good start, the blog suffered from neglect, especially after I had a second child. So it went dormant until 2015, when the opportunity to teach regular classes on Chinese cooking at Hot Stove Society, an avocational cooking school in Seattle, revived my need for a recipe blog.

When I was at the newspaper, my column was a weekly trigger for home cooks to reach out to me with questions or comments about recipes of all types. I learned as much from the readers as they learned from me. After I left the paper, that channel of exchange became nonexistent. It took five or so years away from the day to day of journalism to give me the perspective I needed to understand what I had missed about being a columnist: telling universal stories through the lens of cooking, eating, and thinking about food—and, more importantly, being in a position to convey cooking skills to a broad audience in order to empower them to feed themselves and their families deliciously, simply, and wholesomely. I knew that I needed to return to the food community in some way to regain that connection with home cooks. Through monthly cooking classes on how to make pot stickers, soup dumplings, and simple stir-fries, the path back into the conversation opened up again.

My ultimate goal is to get you into the kitchen. Chinese cooking can be daunting because the ingredients and methods are unfamiliar, and, if you haven’t experienced the diversity of regional Chinese dishes, your palate may not have a baseline for the flavor profiles. The complaints I hear most often about why people don’t cook Chinese food are that the ingredients seem too “exotic” and that cutting all the ingredients is so much work. The most common “aha” I hear after students attend a class, however, is that a given dish wasn’t as hard to cook as they thought. Even one of my chef colleagues at the cooking school, for example, commented that she was surprised at how accessible—and delicious—many of my recipes are. I think our brains are wired to associate long lists of ingredients with a higher degree of difficulty, causing us to see a greater challenge than exists. I make it a point to remind all the home cooks I meet to have a growth mind-set: You will likely have some “mess ups” to start, and that’s okay. You will improve only if you first develop a

habit of cooking Chinese dishes. When you internalize some of the basic principles, you will be able to improvise based on what’s available. Chinese cooks, in general, don’t start with a recipe or menu. They are more likely to let the ingredients on hand, and any leftovers, determine what they cook. They are more concerned with balancing the components and flavors of a meal than following a particular recipe. Perhaps your journey starts with cooking a Chinese meal once a week and building from there. Don’t fret about not having the exact equipment or the full complement of specialty ingredients. Yes, having appropriate equipment, in general, makes it easier to cook. But, ultimately, Chinese home cooking is about being resourceful and adaptable. Any kitchen can be a Chinese kitchen.

When my parents first arrived in Columbia, Missouri, in 1975 with two young children and a few suitcases, there were no Asian markets. They had to shop at IGA, Schnucks, and Kroger, where they couldn’t even find napa cabbage or any other familiar ingredients. They had to drive ten hours north to Chicago to stock up on good soy sauce. We had secondhand cookware and a humble food budget. We lived in a tiny apartment in a university-owned complex for graduate and married students. And yet, my parents cooked Chinese meals every day.

It’s this food that sustained me in those early formative years. I have clear memories of being four or five years old, standing on my toes trying to watch my mother make dumplings; of slurping too-hot chicken soup with ginger and shiitakes while sitting at our white metal dinner table; of eating bowls of rice topped with red-braised pork; of the very special occasions when my father would splurge for frozen Alaskan snow crab to stir-fry with green onions, ginger, and garlic. I also can hear the dull sound of wooden chopsticks tapping the bottom of the small aluminum pot that my parents used to make rice, soup, and even the Kung-Fu brand instant noodles that, to this day, I will eat on occasion.

By the time my parents opened a restaurant in 1980, it was easier to get Asian ingredients in Columbia. There were specialty wholesalers in Saint Louis that would send their trucks an hour and a half to our town to deliver to us and the other Chinese restaurants. Having access to authentic ingredients did not mitigate our customers’ demands for deep-fried sweet-and-sour pork, cream cheese wontons, chop suey, cashew chicken, and the like. They wanted cheap and fast Chinese food that satisfied their sweet tooth. During the twenty-three years the restaurant operated, the turning point came in the mid-1990s when my parents pivoted from full-service dining to a buffet restaurant. Business increased substantially, which certainly benefited the family, but while much of the menu reflected Americanized dishes, we billed ourselves as a home-style Sichuanese restaurant. We offered classic dishes, such as ma po tofu, dry-fried green beans, fish-fragrant eggplant, kung pao chicken, and twice-cooked pork. These were far from best sellers, but they were dishes my parents liked that reminded them of home. Neither of them were born in the Sichuan Province in China, however. Their palates were shaped by war.

My mother’s family was from the north in Manchuria and my father’s family was from Henan in central China. Because my grandfathers were both officers in the Kuomintang’s National Army, they and their families retreated to Taiwan when the Communists took over in 1949. All the mainlander military families settled in what initially were meant to be provisional villages throughout the island. The culinary result of this displacement of people from diverse regions across China who now were surrounded by Taiwanese culture was a delicious intersection of influences on home cooking. This thread carried through to our family’s restaurant. The Chinese name my parents coined for the restaurant translates roughly to “homeland cooking” or “home-style eats.”

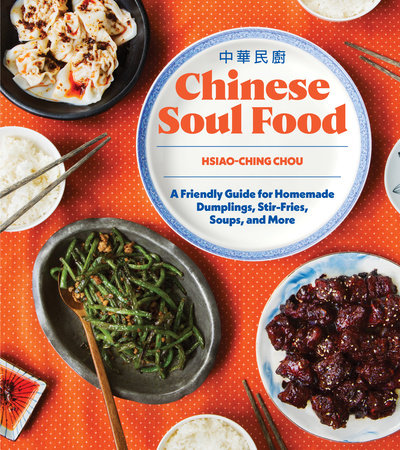

Similarly, the Chinese name for this cookbook loosely translates to “Everyone’s Kitchen.” The spirit of the name connects to the heart of the cooking in this book, which is grounded in this legacy of intertwined regional traditions and resourcefulness. I can take small liberties to accommodate taste preferences or apply refinements to the techniques and choice of ingredients, but the recipes all have humble origins. Comfort comes in the tingling

ma la (or “numbing spice”) of Sichuanese ma po tofu, the nuance of northern steamed dumplings, the caramelized richness of Taiwanese braised beef noodle soup. It isn’t high cuisine. It is Chinese food for the soul.

Copyright © 2022 by Chou, Hsiao-Ching. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.