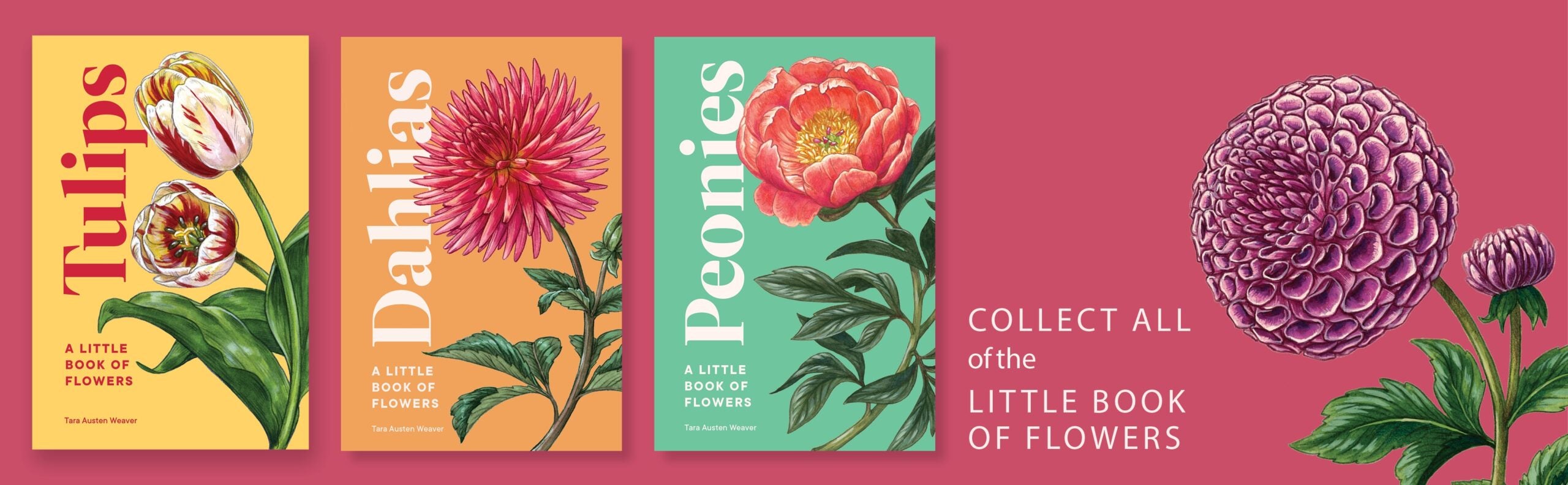

Origin of the Species

“There’s probably no plant in the flower kingdom that gives the gardener more spectacular reward than the dahlia.”

—RAY ALLEN

Dahlias are the showgirls of the flower world—extravagantly beautiful, they sashay into the summer garden and demand all our attention. But like any stage performer, their beauty is deceptive. Dahlias are hard workers and strong, putting out bloom after bloom from midsummer right into autumn. The show finally ends with the first hard frost, which brings down the curtain on their dazzling performance. Few flowers produce for so long, with such diversity of color, size, shape, and cutting potential. If ever there was a bloom that earned its keep, it’s the dahlia.

The modern dahlia traces its roots to Mexico and Central America, where they were cultivated and gathered wild by the Aztecs and other indigenous people, prized more for their edible roots and hollow stems that were used to carry water than for the flowers themselves. The name for dahlias in the Nahuatl language spoken by the Aztecs is acocoxochitl, which translates as “water tube flower.” Dahlias root tubers were also used for their curative properties—to treat ailments such as epilepsy, fevers, urinary tract disorders, and colic. The petals were known to soothe rashes, insect bites, and dry skin.

When European explorers arrived from Spain in the late 1500s, they were intrigued by the flowers they saw growing wild on sunny hillsides. The blooms were fairly simple, with a single row of petals, but all attention was focused on the tubers—plump underground roots that resembled a sweet potato in shape. The first drawings of what we know as dahlias were published in Europe in 1651.

By the late eighteenth century dahlias themselves had arrived in Europe—sent by the director of the Botanical Garden in Mexico City to the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid, where they were named for the famous Swedish botanist Anders Dahl. Initial interest in the edibility of the tubers quickly faded (they are fibrous and can cause digestive upset), but this era was marked by great botanical exploration, where European botanical gardens, noted horticulturists, and the aristocracy were vying to acquire the rare plants that were being brought from all corners of the globe.

By the early 1800s, dahlias had made their way to France and England, eagerly sought after and in high demand. The flowers were still quite simple, but that soon was to change. The 1800s saw a frenzy of dahlia introductions across Europe—the anemone dahlia was developed in Ireland, while the charming collarette emerged in France, and the formal decorative in Germany. The spiky cactus form was introduced by the Dutch, the lone surviving dahlia tuber from a crate that had been shipped from Mexico but rotted during the journey. Dahlias became a hobby of the wealthy (or, rather, the work of their gardeners). Tubers could be purchased but they were not cheap and flower shows offered

generous prizes for exciting new blooms. As growers throughout Europe began breeding dahlias, more decorative blooms were developed. By 1836, the Horticultural Society of London (now the Royal Horticultural Society) published a dahlia register that listed seven hundred different varieties of the flower. The year prior had seen forty-five different dahlia shows held in Britain alone. Dahlia fever was taking hold.

The Great Exhibition, held in London in 1851, put the dahlia on the map in a new way, introducing it to a wider cross-section of society and increasing demand. The upper classes had been installing “dahlia walks” in their gardens—grassy paths lined with wide beds of dahlias so they could admire the blooms—but now the average backyard gardener wanted dahlias as well. Dahlias were said to symbolize dignity to the Victorians, with their upright stalks, though the meaning broadened over time to include elegance, respect, compassion, and a lifelong bond.

Part of the success of the dahlia is due to how easy they are to hybridize. Most dahlias are grown from tubers, resulting in an exact clone of the original flower. By collecting and planting the seed of any dahlia, however, you will grow a combination of the original dahlia and whatever dahlia whose pollen was brought by bees or other pollinators. As a result, there are fifty-seven thousand named cultivars of dahlias, with more being introduced each year (for comparison,

there are only three thousand named rose cultivars).

This excitement for dahlias continues today—in new varieties that are released to the public, in the delight of seeing the first bloom of a new cultivar in the garden, in the generosity of a plant that starts off in midsummer and blooms straight until frost takes it down, in the fact that cutting flowers is a sure way to encourage more blooms. It’s no wonder that people so easily become obsessed with the dahlia.

Copyright © 2022 by Tara Austen Weaver. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.