It is a truth universally acknowledged, that every writer dreams of an ideal reader. Two very real readers volunteered for that role, relieving me of my daydreams: Henry Adams, who knew nothing of my four years as Bernstein’s assistant, and David Thomas, who knew everything, but from a tangential slant. My thanks to Henry and David for steering me toward the better word, the consistent voice, and the honest examination of these four peculiar years.

Though he wrote the definitive Bernstein biography, Humphrey Burton said the cheeriest words imaginable, after seeing a few sample chapters: “All this is new to me,” what every memoirist wants to hear. Humphrey’s candor gives me hope that this memoir fills a niche. Thank you, Humphrey and Christina.

My thanks to all who read sample chapters and begged for more: Alison Ames and Cage Ames; Alexander Bernstein, Jamie Bernstein Thomas, and Nina Bernstein Simmons, whose joy and kindness are the finest tributes to their remarkable parents; Helene Blue; John Clingerman and Douglas Myhra, Colin Dunn and Bruce MacRae, my adopted siblings on two continents; Paul Epstein, who should have a late-night TV show explaining legal terms; Ella Fredrickson; Roger and Linda James; Liz Lear and Deems Webster, whose every conversation leads to more Bernstein memories; Laurence McCulloch and Bill Hayton; Mike Miller and Tim Weedlun, for housing me during my Library of Congress immersions; Lee and Tony Pirrotti; Rene Reder and Dan Keys; Tony Rickard; Marilyn Steiner; Tom Takaro; Mark Adams Taylor; Leslie Tomkins and Michael Barrett, cheerleaders from the get-go; Alina Voicu and Daniel Szasz; Charles Webb, witness to my long journey; and Mark Wilson.

Affectionate thanks to the friends and colleagues of Leonard Bernstein, living and departed, consistently encouraging me as I blindly batted my way through the years I write about in this memoir, starting with those I think about every day: Jennie Bernstein and her sisters Dorothy Goldstein and Bertha Resnick, Margaret Carson, Betty Comden, Ann Dedman, Adolph Green and Phyllis Newman, Patti Pulliam, Sid and Gloria Ramin, and indispensible Julia Vega.

Gratitude also to: Schuyler Chapin, Helen Coates, Jack Gottlieb, Desi Halban, Dorothée Koehler, Harry Kraut, Robert Lantz, Arthur Laurents, James Levine, Christa Ludwig, John and Betty Mauceri, Erich and Jutta Mauermann, Carlos Moseley, Harold Prince, Jerome Robbins, Ned Rorem, Avi Shoshani, Stephen Sondheim, Roger and Christine Stevens, Michael Tilson Thomas and Joshua Robison, Hans Weber, Richard Wilbur, Harriet Wingreen, and Stephen Wadsworth Zinsser.

Thanks to the many people I met through working for Bernstein, who remain friends to this day: David Abell and Seann Alderking, Phillip Allen, Marin Alsop, Franco Amurri, Betty Auman and Chris Pino, Ellen and Ian Ball, Suzanne Baumgärtel, Johnny Bayless, Burton Bernstein, Daryl Bornstein, Serge Boyce, Justin and Elaine Brown, Garnett Bruce, Marshall Burlingame, Finn Byrhard, Flavio Chamis, Steve Clar, Bruce Coughlin, Ned Davies, Emil DeCou, Clare Dibble, Gail Dubinbaum, Jobst Eberhardt, Roger Englander, Marcia Farabee, Joel Friedman and Jenny Bilfield, Carlo and Giovanni Gavazzeni, Domiziana Giordano, Linda Golding, Dan Gustin, Erik Haagensen and Joe McConnell, Kuni Hashimoto, Connie Haumann, Barbara Haws and William Josephson, Marilyn Herring, David Israel, Diane Kesling, Sue Klein, Frank Korach, Eric Latzky, Holly Mentzer, Linda Indian, Gail Jacobs, Wolf-Dieter and Amalia Karwatky, Peter Kazaras and Armin Baier, Jim Kendrick, Steve Masterson, Larry Moore, Richard Nelson, Clint Nieweg, Kurt Ollmann, Richard Ortner, Eiji Oue, David Pack, Kevin Patterson, Gidon Paz, Shirley Rhoades Perl, Charley Prince, Philip von Raabe, Gottfried Rabl, Madina Ricordi, Hanno Rinke, Paul Sadowski, Asadour Santourian, Karen Schnackenberg, Jonathan Sheffer, George Steel and both Sarahs, Aaron Stern, Mimsy Gill Stirn, Steve Sturk, Robert Sutherland, Larry Tarlow, Auro Varani, Alessio Vlad, Johnny Walker, Ray White, Fritz and Sigrid Wilheim, John Van Winkle, Paul Woodiel.

Craig Urquhart gets a thank you all his own; he held the fort.

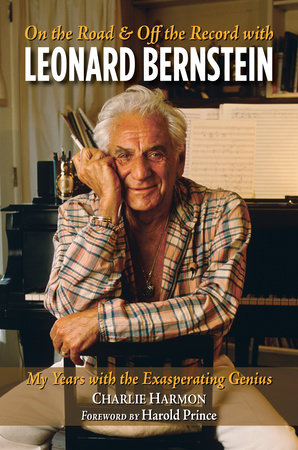

Thanks to the photographers whose quick eyes preserved LB as we knew him: Ann Dedman, Arthur Elgort and Grethe Holby, Andy French, Henry Grossman, Robert Millard, Patti Pulliam, and Thomas Seiler.

Thanks to Mark Horowitz at the Library of Congress, stalwart keeper of the Bernstein flame for the nation.

To Sallie Randolph, who assisted me with legal matters: this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Thanks to Larry Leech, for pointing out the difference between a journal and a memoir at the June, 2015, Florida Writers Association workshop.

To Ann Hood, instructor of the memoir workshop at the January, 2017, Writers in Paradise conference at Eckerd College: I pledge eternal vigilance at your shrine. Never has there been a more knowledgeable guide since Virgil accompanied Dante, though Ann traverses a happier terrain. High fives to the inspired colleagues I met at Writers in Paradise: James Anderson, Mary K. Conner, Colleen Herlihy, Molly Howes, Karen Kravit, Antonia Lewandowksi, Joan McKee, Meredith Myers, Carlie Ramer, Honey Rand, and Donna Walker. I never knew genius had a plural.

Gratitude beyond measure goes to my agent Eric Myers, the first to call, and the firmest believer in the story I wanted to tell.

To my editor, Don Weise and Mary Ann Sabia at Charlesbridge, thanks compounded with admiration for turning that most ephemeral of human abstractions, memories, into a tangible book. You know your business!

A last bow goes to Harold Prince for writing a foreword with grace and polish. Mr. Prince energetically burnishes the Bernstein legacy, year after year. I’m his fan forever, and am forever in his debt.

Copyright © 2018 by Charlie Harmon (Author). All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.