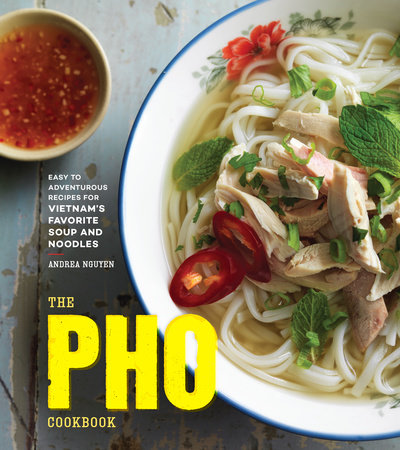

What is Pho?Pho is so elemental to Vietnamese culture that people talk about it in terms of romantic relationships. Rice is the dutiful wife that you can rely on, we say. Pho is the flirty mistress that you slip away to visit.

I once asked my parents about this comparison. My dad shook his hips to illustrate the mistress. My mom laughed and quipped, “Pho is fun but you can’t have it every day. You would get bored. All things in moderation.”

The soup first seduced me in 1974, when I perched on a wooden bench at my parents’ favorite pho joint and wielded chopsticks and spoon with dexterity and determination. The shop owners marveled; mom and dad beamed with pride. The fragrant broth, savory beef, and springy rice noodles captivated me as I emptied the bowl. I was five years old and suddenly hooked on soup. That experience is among the most vivid from my childhood in Vietnam.

After we immigrated to the States in 1975, there were no neighborhood pho shops to frequent in San Clemente, California, where my family resettled. My pho forays were often homemade, for Sunday brunch.

Like many Vietnamese expatriates, we began savoring pho as a very special food, a gateway to our cultural roots. My mother regularly brewed beef or chicken pho broth on Saturday, then the next morning after eight o’clock mass, we sped home. Everyone had a job on Mom’s pho assembly line.

At the table, our bowls of homemade pho were accompanied by fresh chile slices and a few mint sprigs. The simplicity reflected my parents’ upbringing in northern Vietnam, where purity prevailed. They’d lived in liberal Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) for decades, but they didn’t allow embellishments like bean sprouts, Thai basil, or lime wedges. And definitely no sriracha, which Mom deemed un-Vietnamese.

As a college student in Los Angeles, I went to pho restaurants that served up giant bowls with plates piled high with produce for personalizing flavors. Flummoxed at first, I learned to loosen up, even at the sight of someone squirting hoisin and sriracha into a bowl. Over the years, I practiced making my own pho, developed recipes for my first cookbook,

Into the Vietnamese Kitchen (2006), researched pho in Vietnam and wrote articles on it, answered reporter and blogger queries, and taught pho classes to countless cooks.

Interest in pho has risen exponentially as it has moved from the margins to the mainstream. It’s a favorite food for many but it’s also been the focus of novels, art exhibits, rap songs, and Kickstarter campaigns. People are smitten by Vietnam’s signature dish for many reasons: Pho is comforting (noodles in clear broth satisfy), healthy (there’s little fat and gluten), restorative (try it for colds and hangovers), and friendly (you can have it your way). It’s also delicious.

I figured that I knew what pho was all about until friends, Facebook fans, and then my publisher suggested that I write a pho cookbook. Seriously? What was there to present beyond the familiar brothy bowl? As it turned out, a lot. It didn’t take me long to realize that the world of pho was unusually rich with culinary and cultural gems.

CASHEW, COCONUT, AND CABBAGE SALAD Serves 4 to 6 as a side dish Takes 20 minutes

Pretty and bright, this vegan salad incorporates coconut’s lushness by way of toasting unsweetened coconut chips (large flakes of dried coconut) with flavorful virgin coconut oil. It’s a handsome side that refreshes the palate—a perfect pairing for any of the main dishes in this book as well as the pot stickers on pages 129 and 131. Feel free to prep the ingredients hours in advance and toss at the last moment.

DRESSING 2 medium limes

Unseasoned Japanese rice vinegar, as needed

1 1⁄2 tablespoons sugar

1 1⁄2 tablespoons regular soy sauce

1 1⁄2 tablespoons canola or other neutral oil

1⁄4 teaspoon fine sea salt

1⁄8 teaspoon pepper

1 small or 1⁄2 large jalapeño or Fresno chile, seeded and finely chopped

SALAD 1 teaspoon virgin coconut oil (optional)

2⁄3 cup (1.5 oz | 45 g) toasted unsweetened coconut chips

1⁄2 cup (2.5 oz | 75 g) salted, roasted cashews, halves and pieces

2 1⁄2 cups (7 oz | 210 g) packed shredded red cabbage

1 1⁄2 cups (5 oz | 150 g) matchstick-cut jicama (1⁄2 small jicama)

3 tablespoons finely chopped fresh cilantro, mint, Vietnamese coriander (rau răm), Thai basil, or a mixture

Make the dressing Use a Microplane or other fine-rasp grater to zest the limes, letting the fragrant peel drop into a large mixing bowl. Juice the limes to yield 1⁄4 cup (60 ml); add a little vinegar if you’re short. Add the juice to the zest along with the sugar, soy sauce, and oil. Stir to dissolve the sugar. Season with salt and pepper to create a balanced, savory-tangy note. When satisfied, add the chile. Set aside.

Make the salad Put the coconut oil (if using for extra flavor) and coconut chips in a skillet. Stir over medium heat for 4 to 5 minutes, until the coconut has slightly darkened and glistens (if the oil was used). Cool in a shallow bowl.

Replace the skillet on the burner and add the cashews. To refresh their flavor, toast over medium-low heat for about 2 minutes, stirring constantly, until faintly fragrant; a few dark brown spots are okay. Slide off heat to cool completely before adding to the coconut.

To serve, toss the cabbage, jicama, and herbs with the dressing. The vegetables should slightly soften and look compacted in about 60 seconds. Add the coconut and cashews. Toss well and transfer to a plate or shallow bowl, leaving any excess dressing behind. Serve.

Notes Coconut chips are often sold at health food stores in the bulk bins. If starting from untoasted coconut chips, cook them for about 7 minutes in the skillet with the coconut oil. Use medium heat, stirring frequently. After a few chips show a bit of golden brown, around the 5-minute mark, lower the heat to coax even cooking without burning. When done, the coconut chips should be golden brown and fragrant.

Copyright © 2017 by Andrea Nguyen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.