Introduction

A green, neatly cut lawn has long been part of the American dream of homeownership.

Since the development of our earliest suburbs, lawn has occupied a privileged place as the default groundcover for builders and homeowners alike. In the late 1800s, Frederick Law Olmsted, the founding father of American landscape architecture, sought to elevate our nation’s homesteader aesthetic of bare dirt, vegetable patch, and fenced yard for keeping out livestock. He looked to the greenswards of grand English estates and envisioned an uninterrupted carpet of lawn spread across new suburban developments, unbroken by fence, hedge, or wall (unlike the aristocratic English model)—a commons shared by each homeowner, whose civic responsibility included maintaining his own piece of it. Lawn, proclaimed Olmsted, would be an expression of democracy. Drive the neighborhood streets of almost any town in the United States today and you’ll see Olmsted’s vision brought to life, with one lawn flowing into the next all the way down the block.

It’s easy to see how the lawn became so popular. When maintained with water and regular grooming, it covers the ground superbly and can be used for play and relaxation. Installing a lawn is fairly inexpensive, and the tidy openness of a lawn is comfortably familiar. Lawn culture—weekly mowing and edging, running the sprinkler in summer, and applying chemical fertilizer, pesticides, and weed suppressants—became firmly entrenched in the 1950s, when home ownership surged, and today many homeowners’ associations (HOAs) and city councils have codified standards for a front lawn that each resident must maintain. Just look at the lawn-care aisles—packed with chemicals, hoses, and equipment—at your local home-improvement store to see what a big business lawn maintenance has become.

The Grass is Not Always Greener

The fact is, however, that traditional lawn grasses aren’t well suited to large regions of our country—the arid Southwest and Mountain West, in particular, as well as the drought-prone Plains states—and lawns in the South and Midwest often require copious summer watering to be kept green. Lawn fertilizers and pesticides have proved toxic to birds, to beneficial insects, and, when they wash into watersheds, to fish and rivers. Lawns lack cover, food, and nesting material for wildlife. A typical lawn requires several hours of maintenance each week during the growing season, and the power tools used for this time-consuming maintenance come with a high cost in terms of air and noise pollution.

Today, we have a better understanding of the lawn’s impact on the environment. We’re mindful of water shortages, runoff tainted by lawn chemicals, and air and noise pollution caused by maintenance equipment. We’ve come to recognize that the look of a more native landscape is worth cultivating and nurturing. Why should the average homeowner in the arid high country of the Southwest, for example, emulate a lush Southeastern landscape, or vice versa? In other words, why deny the particular beauty of your own region? All around the country you can find the same few species of lawn grasses and foundation shrubs making up a national, undifferentiated residential landscape. It’s like driving cross-country on the interstate and seeing the same four fast-food restaurants at every exit. We deserve better—and we can make it happen.

A Greener Way

Most people hardly use their lawns, especially the front lawn, and it can seem an awful waste to maintain something that you never use. Moreover, other types of plants also do a beautiful job of covering the soil, and many of them require less water and maintenance. Simply by choosing to grow several different species of plants in your yard, you’ll help reduce the “lawn desert,” a monoculture of turf that afflicts so many neighborhoods.

Also, by growing swaths of plants well adapted to your local conditions and including appropriately scaled hardscape—like paths and patios—you’ll ultimately use fewer resources and create a better-looking landscape for your home. You may also spend fewer hours maintaining it. Most rewardingly, you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing that you aren’t harming the environment and you’re maintaining a landscape that invites you to enjoy it. Let’s reclaim our outdoor spaces for relaxation, natural beauty, wildlife habitat, and a sense of living more lightly on the earth.

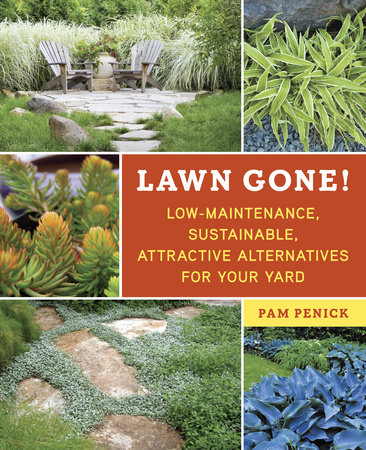

Lawn Gone! will inspire you with examples of real-life, lawn-free landscapes and show you how to achieve a beautiful yard with practical information about removing the lawn and landscaping without traditional grass (or, at least, with less of it). Whether you’re considering removing all or part of your lawn, Part One will show you different options for covering your soil with low, ground-covering plants, welcoming patios and paths, and enticing features like ponds, firepits, and garden pavilions. When you’re ready to begin, Part Two will walk you through the various methods of lawn removal and explain how to install hardscape and plant your new garden.

If you have HOA rules or city ordinances to contend with, you’ll find Part Three especially helpful. This section also addresses garden pests and ways to minimize their impact and explains how to create a wildfire-resistant landscape. In Regional Plant Recommendations, you’ll find plant picks and local gardening information contributed by regional experts, helping you to pinpoint plants that will thrive in your region.

By picking up this book, you’ve already taken the first step toward a greener way of landscaping. Now let’s explore the possibilities and get inspired!

Copyright © 2013 by Pam Penick. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.