Introduction

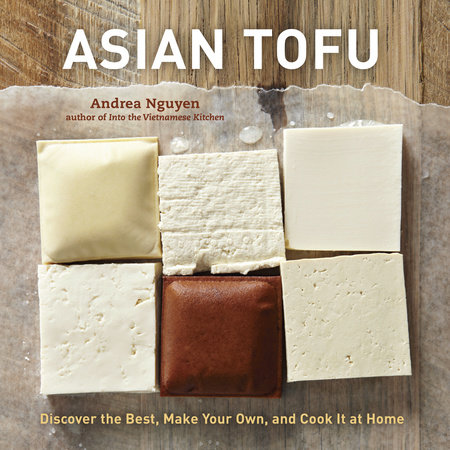

Despite all the terrible terms that have been attached to tofu, it is still considered a good four-letter word by countless people. As an Asian staple, it is beloved by rich and poor alike. Whether fresh and tender or aged and fermented, tofu denotes basic sustenance, culinary craftsmanship, time-honored traditions, good health, and more. Tofu pervades many aspects of Asian life and culture, as I discovered during my travels and research for this book.

For example, visit a country in East or Southeast Asia and you’ll see tofu practically everywhere, on restaurant menus, as street food, and at cafeterias. You can buy it from open-air (“wet”) food markets and neighborhood tofu shops as well as fancy food halls and superstores such as Walmart and Carrefour. Small packages of tofu snacks are often displayed as impulse buys at Chinese hypermarkets.

There are even ample opportunities for tofu tourism. A popular excursion from Taipei is to “The Capital of Tofu” in Shenkeng, renowned for its tender tofu and old-fashioned methods, such as cooking the soy milk over wood charcoal for a light smokiness. Under the archways that line the charming Old Town area, vendors sell a variety of tofu, including tofu ice cream, grilled stinky tofu on a stick, and salty-sweet fermented tofu.

Among the highlights of visiting Kyoto are elaborate multicourse tofu meals and tofu shops that date back to the 1800s. Tokyo offers elegant tofu fine dining restaurants, but in the outer stalls of the Tsukiji market, you’ll come across the twenty-something Table-Mono tofu vendors hawking super rich soy milk, tofu, and ice cream to passersby.

Tofu is featured in many Asian cookbooks but it has also been spotlighted in comic books and children’s books. It has inspired artists and designers to create posters, sculptures, and even tofu MP3 speakers and lamps! Few other foods can rival tofu’s significance to so many people.

East Asian Stronghold

While people agree that tofu is an ancient food, no one is clear on when it was invented and by whom. Soybeans are native to China and were considered one of five sacred “grains.” As a primary foodstuff, the soybean’s main virtues were its ability to grow well in poor soil without depleting the land, and its consistently high yield. The little bean was a useful famine food and the Chinese took to transforming it. Initially it was made into a type of gruel, and later into palatable staples such as soybean sprouts, soy sauce, and tofu.

Legend holds that King Liu An of Huainan invented tofu, and excavated tomb carvings point to tofu being made as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Scholars also suggest that the Han Chinese may have learned about rendering curds from milk through contact with nomads from the northern steppes. However, tofu did not catch on as a popular, commercially made food until the tenth century, when the Mandarin term

dou fu (tofu) was mentioned numerous times in literature.

It was from the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) onward that tofu spread to other parts of the region. Wherever the Chinese exerted their influence, whether through religion, politics, or trade, tofu went with them. That’s why so many Asian tofu dishes are Chinese in origin.

How tofu knowledge flowed from China to other cultures, however, is murky. For example, monks and scholars traveling between China and Japan may have transmitted tofu culture to Japan between the eighth and twelfth centuries. It was first mentioned in Japan in 1183 as a Shinto shrine offering, but the characters as we know them today were not written in Japan until 1489. What is generally agreed upon is that tofu was not part of everyday Japanese eating until the middle of the Edo Period (1603–1868). Some support the theory that the Japanese learned about tofu from the Koreans, as a result of the Japanese invasions of Korea between 1592 and 1598. In any event, Japan took to tofu in a big way, evidenced by the 1782 bestseller

Tofu Hyaku Chin by Ka Hitsujun. Among the book’s one hundred tofu recipes are enduring classics, such as

hiya yakko (chilled tofu; page 51) and

yu dofu (simmered tofu; page 87).

Korea and China share a border, and tofu was likely introduced to Korea in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Historic records show that it even played a role in diplomacy. In 1434, as part of their tribute relationship, the Chinese emperor requested Korean cooks skilled at making dubu (tofu) preparations. By the fifteenth century, tofu had indeed become widespread in Korea, though it was mostly made by Buddhist monks as temple food. It was part of an annual ceremony to memorialize the deceased, a practice that continues today.

Wavering Southeast Asia

Vietnam was also a major player in China’s tribute system and a Chinese colony for a millennium, from 111 BCE to 939 CE. Additionally, Vietnamese Buddhism is closely aligned with Chinese Buddhism. Given all of those factors, Vietnam stands out among the Southeast Asian countries as having a broad array of tofu (

dau phu or

dau hu) dishes, including Chinese favorites and many native preparations, such as Lemongrass Tofu with Chiles (page 108). The Vietnamese also developed an extensive vegetarian repertoire that included tofu-based mock meats and fake fish sauce.

While tofu is present in other parts of Southeast and South Asia, it is not a huge deal. According to Thai food authority David Thompson, tofu was a latecomer to the Thai table: “Bean curd is a Chinese import and stayed in that community up until the 1930s when the Chinese and their food became more accepted in Thailand. And so such a relatively short time has meant very little use in pure Thai food.”

While tofu may be added to curries as a meat substitute, included in simple stir-fries and added to noodle dishes, the Thai repertoire includes few tofu-centric preparations. In general, tofu is treated in a Chinese manner, such as being deep-fried and eaten with sauce, or it plays supporting role, as exemplified in pad Thai (page 184). The fermented tofu preparation (

lon tao hu yi, page 148) is an unusual dish that presents tofu in a Thai manner.

People living in Cambodia and Laos enjoy tofu dishes that are often borrowed from Chinese traditions. However, they also invent some of their own, such as the Hmong poached chicken and tofu meatballs on page 129.

In multicultural and multireligious Singapore and Malaysia, treats such as grilled stuffed tofu pockets (page 67) satisfy the dietary needs of Muslims, Buddhists, Christians, and others. While tempeh (fermented soybeans) is king in mostly Muslim Indonesia, tofu is a strong runner-up in terms of popular soy-based foods. Indonesia was part of the spice trade route, which explains original creations such as twice-cooked

tahu bacem (page 112) from Java.

The Chinese brought tofu to the Philippines but locals didn’t adapt it to their cuisine in a significant way. Filipino cookbooks rarely include tofu recipes. As contribution to my research, freelance writer and food blogger Tracey Paska informally polled relatives and tofu vendors at the popular Cubao wet market in Metro Manila. She asked them to name Filipino tofu preparations. Aside from

tokwa’t baboy, a dish of fried tofu, boiled pork, and vinegary soy sauce, people could not name any other traditional dishes that featured tofu. However, Chinese Sweet Tofu Pudding with Ginger Syrup (page 195) is a very popular snack.

Myanmar (formerly Burma) is something of a rogue tofu country. Burmese cooks employ a different kind of tofu. Irene Khin Wong, the owner of Saffron 59 Catering in New York City, explained that soybean-based tofu is a Chinese import that endures in her native country. However, the prevailing and more popular Burmese tofu (also called Shan tofu) is made from ground legumes that are cooked in a polenta-like manner and then cooled and cut. Tofu can be made from many kinds of legumes, including lentils and peanuts, but this book focuses on the soybean version.

South Asian Newcomer

Although soybeans had long been a minor crop in India, tofu didn’t arrive until 1976 when a tofu shop was established near Auroville, an experimental utopia in southwest India. According to the SoyInfo Center, Westerners made that tofu.

Renowned author and teacher Julie Sahni explained that India was a late tofu adopter because initially soy milk and soybean curd were presented as substitutes for cow’s milk and paneer. While Indians who had contact with the Chinese were open to those soybean products, many others took offense at the notion that a bean could replace the precious foods produced from cows, revered and sacred animals in their culture. “It was too close for comfort, too competitive, and very difficult to accept,” she said.

Much had changed by 1985, Sahni noted in

Classic Indian Vegetarian and Grain Cooking, as tofu was gaining popularity in India as a protein-rich, healthy substitute for traditional paneer cheese. Many Indian cooks have picked up on tofu since then. The saag tofu and cashew and tofu fudge recipes (pages 121 and 201) demonstrate how some people integrate tofu into traditional preparations. Today, India is the world’s fifth largest producer of soybeans.

Tofu in America

I was born in Vietnam but grew up in America, and tofu was regularly on our family’s table, a natural extension of my Asian heritage. This isn’t the case for most Americans, despite the soybean’s long history in the United States.

British colonist Samuel Bowen planted the first soybeans in Savannah, Georgia, in 1765 and made his own soy sauce. A few years later, Benjamin Franklin sent seeds from London to a botanist in Philadelphia, citing Italian friar Domingo Navarette’s 1665 account of Chinese tofu. By the 1850s, Midwestern farmers were cultivating soybeans from Japanese seeds, thanks to precocious travelers and Commodore Matthew Perry’s historic expedition and trade mission to Japan.

Though some Americans experimented with eating soybeans during the 1800s, people mostly knew only of soy sauce. The US soybean crop was mainly used to feed animals and enrich soil with nitrogen. However, Americans turned to soy as a source of nourishment during wartime and periods of deprivation. For example, Civil War soldiers in the southern states drank a coffee substitute made from ground roasted soybeans.

In the early part of the twentieth century, the USDA sent expeditions to Asia to investigate traditional soy foods and growing methods. Agricultural explorers Charles Piper and William Morse detailed their findings in

The Soybean (1923), a historic publication that included recipes to encourage Americans to consume soy foods. Innovators George Washington Carver and Henry Ford both championed soybeans for cooking and also collaborated on developing soy-based plastics. Ford hosted multicourse soybean feasts and developed an experimental “Soybean Car.”

Mildred Lager’s

The Useful Soybean (1945) presented well-researched and impassioned arguments for adopting soybeans as a natural food. Unfortunately, her efforts did not alter prevailing attitudes toward the bean. Americans still perceived it as a nonfood, though they indirectly consumed it via livestock raised on soybean meal, vegetable oil, and other processed foods. During and after World War II, farmers in the US began cultivating soy as a major cash crop, turning it into one of country’s most important agricultural commodities. America is currently among the world’s biggest soybean producers and exporters.

From Alternative to Mainstream

In 1958, Boys Market in Los Angeles became the first American supermarket to sell tofu. However, tofu did not get a real boost in the US until the 1970s, when it became part of the natural foods and sustainable eating movement. Frances Moore Lappe’s

Diet for a Small Planet (1971) and William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi’s

The Book of Tofu (1975) detailed the ecological, health, and culinary benefits of tofu.

Shurtleff and Aoyagi’s work encouraged people to make tofu and prepare vegetarian fare. Their extensive exploration of Japanese tofu shops and cuisine underscored how tofu was an efficient means to use the Earth’s natural resources. “I wanted to make a contribution to the planet,” Shurtleff explained in a 2010 conversation. Organic tofu pioneer Jeremiah Ridenour, who traveled with Shurtleff and Aoyagi in the 1970s and eventually cofounded Wildwood Natural Foods, succinctly put it this way: “It’s about feeding the world. We have to be eating at the beginning of the food chain.” Tofu activists such as Shurtleff and entrepreneurs such as Ridenour helped reframe tofu for their generation. As a result, tofu took on a New Age aura of Asian trendiness and organic living. Before that, the American tofu scene remained in the realm of Asian American–owned tofu shops and vegetarian Seventh-day Adventists. The economic upheaval of the 1970s gave way to the boom years of Reaganomics, and many of the Americans who tasted tofu in the guise of Western fare disliked it. In fact, a 1986 Roper Poll published in

USA Today listed tofu as the nation’s most loathed food.

Burdened with a “bland white cake in water” image, tofu got a marketing makeover in the 1990s as manufacturers answered consumers’ call for healthy foods. Nondairy Western products such as Tofutti ice cream and tofu chocolate Americanized tofu and converted many skeptics. In 1990,

The Tofu Book by John Paino and Lisa Messinger declared tofu the foundation for a new American cuisine.

The Los Angeles Tofu Festival debuted in 1996 and had a successful run until 2007, attracting thousands of people annually with clever themes and taglines such as “Tofuzilla” and “It’s hip to be square.” Over the past decades, tofu publications, better awareness of Asian cultures, and robust Asian American communities have contributed to greater appreciation for tofu as a healthy, affordable food source.

Tofu Today In a 2008 survey of 1,000 adults, the United Soybean Board found that 85 percent of Americans understand that soy is healthy, a 26-point rise since 1997. The USDA’s recently released 2010 dietary guidelines recommended soy products and soy milk as part of a good diet. On the flip side, there are many who believe that too much soy is harmful to health. Indeed, overconsuming anything can lead to adverse side effects. A wise strategy is to enjoy moderate amounts of minimally processed, natural soy foods, such as tofu, soy sauce, and miso.

That’s easier nowadays because tofu can be found at most supermarkets and specialty grocers. Tofu makers such as Hodo Soy (page 131) are expanding people’s palate for tofu and Dong Phuong Tofu (page 193) are preserving tofu traditions for their immigrant communities. The menus of Japanese

izakaya pubs showcase fresh tofu to appreciative diners. At the same time, curious home cooks and chefs are beginning to experiment with making tofu from scratch.

Tofu is no longer either relegated to food co-ops or considered as a mere meat substitute. The widespread availability of tofu and the shift in mainstream attitudes toward tofu make it more relevant now than ever to the American kitchen. We are not in wartime or suffering extreme deprivation. However, there is increased interest in healthful eating, sustainable living, and authentic Asian flavors.

Many books focus on Western ways with tofu, but this one puts tofu in its original context, as an important Asian staple that people have made, cooked, and enjoyed for centuries. The recipes, stories, and images bridge the Pacific and convey tofu’s timelessness as well as its modern incarnations. If tofu is going to evolve and succeed in the West, Asian approaches need to be involved.

As I “chased the bean curd” for this book, a few food-savvy friends declared a hatred for tofu, but many more (thank goodness) revealed a curiosity about it and even a love of it.

Asian Tofu does not aim to convert, but rather to present tofu traditions as they exist and as they continue to deliciously develop.

I encourage you to explore the techniques and recipes herein. There is much to savor, as tofu can be eaten from morning until night, in no-meat, low-meat, and meaty preparations. It is a flexible food that is open to endless possibilities.

Copyright © 2012 by Andrea Nguyen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.