01 - FIND YOUR PASSION

How to Join the Environmental Movement Have you ever heard the expression, “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good”? When I was beginning my activist journey in college, I spent years trying to decide what issue to work on because I wanted my efforts to be perfectly matched to my interests. I felt like I never had either enough background information to choose just one issue or enough time to devote to all of my passions. If I worked on rainforest conservation in the Amazon, who would work on shutting down toxic waste dumps in the United States? If I worked to save the community garden from closure, how would I find the time to protest the oil company polluting my hometown coastline?

As I waited for the perfect opportunity to get involved, my college career drew to a close—and I hadn’t gotten involved in any issue at all! Over time, I realized that there is no “most critical” or “most important” issue; instead, we all need to work for our biggest passion. My passion is forest protection. As a child, I pored over books and stories about temperate and tropical rainforests. In high school, I decided I would one day study abroad in Costa Rica. When I was nineteen I headed there to study ecology, and I followed that up with a research stint in Panama at the Smithsonian’s tropical research station, where I was able to connect with some of the world’s top tropical ecologists. After my college graduation, I dove into an effort to protect old-growth forests in the United States, and I’ve never regretted my first campaign choice.

While we face an intimidating number of environmental challenges, here’s the good news: millions of individuals worldwide are getting involved. You don’t have to fix everything yourself. Are you outraged by the inhumane conditions of factory farms? Does it break your heart to hear about mountaintop coal mining in Appalachia, modern-day slavery in polluting gold mines, or the climate crisis leading to drought, wildfires, destructive weather, and species extinction around the world? Figure out what your gut and your heart are most excited about, and work on that issue. Activism can be difficult and slow going, but if you truly care about the issue, you’ll be far more likely to stick with it when the going gets rough, rather than burn out and drop out.

Most people become activists because they are compelled to protect the places and people they love. And in many cases, young people become activists because an issue finds them—not the other way around. Ethan Schaffer, for example, got involved in the sustainable foods movement after looking for answers to the question of why he and other young kids were suffering from serious illnesses like cancer.

Success Story

Get Your Hands Dirty

When Ethan Schaffer was fifteen, he was diagnosed with lymphoma cancer. He left his friends in ninth grade and underwent five months of intensive and brutal chemotherapy. Fortunately, the treatment worked and he survived. But the experience changed him. He began to question why kids were getting cancer and started asking what he could do to create change. Eventually this led Ethan to explore healthy and sustainable living by working on organic farms in New Zealand. Revitalized by the experience, Ethan realized that the solution to both health and environmental problems lay in individuals learning to live sustainably. When he returned to the United States in 2001, he launched GrowFood.org. Grow Food helps people experience sustainable living by connecting them with opportunities to work on organic farms. Less than a decade later, the program has connected more than twenty thousand people with opportunities to live, eat, and grow food more sustainably on nearly two thousand farms in all fifty states and in forty-one countries.

“We need to get toxic chemicals off the farm and out of the food system. Organic farming is good for both the planet and people.” -- Ethan Schaffer

Like Ethan, you might choose to work on an issue because it affects your health or the health of friends or family members. Do you or your family members have asthma because local industries are polluting the air? Do you surf in an area with contaminated water? Many of the most passionate advocates I have met are driven by a personal experience dealing with asthma, sickness, cancer, or the unnecessary death of a loved one due to an illness caused by contamination.

Think about your community—your neighborhood, town, or city. Could you work to protect and establish more parks and green space as Connie Shahid did?

Success Story

Finding Your Passion When You’re Not Looking Seventeen-year-old Connie Shahid wasn’t always familiar with environmental issues. A senior in high school, she lived in a San Francisco neighborhood called Bayview-Hunters Point, a polluted and economically depressed area surrounded by freeways, a power plant, and a naval shipyard. She was looking for a job when she encountered Literacy for Environmental Justice (LEJ), an organization that addressed the health and environmental concerns in her community. She began working to combat the destructive effects of industrialization and landfills on the native wetlands that in turn improved the air and water quality. Connie engaged other young people in the effort by putting up posters, speaking to youth groups, and doing outreach in her neighborhood. She served as a model and a mentor to the younger participants as they repaired a community garden, built a 1,200-square-foot shade house to host native plant seedlings, and created a strong community of youth activists who cared about community stewardship.

“Before working with LEJ, I didn’t even know what environmental justice was. It’s changed me, because now I’m more conscious.” -- Connie Shahid

Connie wasn’t looking for a way to get involved in the environmental movement when she ended up finding her passion. If you’re wondering what issue is right for you, start close to home, as she did. What can you do to lessen your city’s environmental footprint, add green space, or clean up the air and water? If you’re a student, starting on campus is a good bet. What are the major opportunities for getting involved at your school? Do you lack a recycling program? Do you want to introduce environmental science courses to the curriculum or launch a campus organic garden?

One strategy for turning passion into action is to identify a meaningful environmental change you have made in your personal life and figure out how to bring that change to a larger group of people or an entire institution, like a campus, your town, or a business. You start by making changes in your personal life, like eating organic food. Organizing takes this one step further by looking at how you can institutionalize those changes to benefit more people (say, starting an organic garden open to community members or convincing your campus to buy at least 20 percent of its produce from organic farmers). The first is personal change; the second is real change for society. Of course, organizing is more work, but its impacts are much more influential, as Diana Lopez can attest!

Success Story

Roots of Change Diana Lopez, twenty, recognized the challenges faced by her community in the east side of San Antonio, Texas, due to the lack of large grocery stores and places to get fresh, organic, or local produce. A growing number of people in her family and community had cancer or diabetes, and she began to look at the linkage between food and health. Talking with elders in her community, she learned that the farming techniques of a hundred years ago kept the ground healthy and the food safe—many of the same techniques now used in organic gardening.

Diana decided to start growing her own organic food—and to offer the option for healthy eating to her community. She cofounded the Roots of Change garden to serve as an educational center and positive space for community gathering. Since 2007 she has worked with hundreds of youth and adults to create a native plant and food garden and to host educational sessions, coordinate student workdays, and provide locally grown produce for the community.

“Everyone deserves the right to a clean, healthy environment, regardless of your color or economic status.” -- Diana Lopez

Or maybe you’re like Dave Karpf. He knew he wanted to get more deeply involved in the environmental movement but wasn’t sure where to start. Not driven by any particular issue, he looked to experienced organizers to find a way to plug in.

Success Story

Save the Belt Woods Dave Karpf’s experience with environmental activism started when he was a junior in high school. As the head of his environmental club, he wanted to find something to work on beyond monthly roadside cleanups. So Dave reached out to the local chapter of the Sierra Club and asked what they were working on. From them, he learned about the Coalition to Save the Belt Woods, an effort to protect the last old-growth forest in Maryland. He had never been to the Belt Woods, but he and his friends cared about wilderness, and this was an opportunity to make a real difference.

Dave created a new group, Montgomery County Student Environmental Activists (MCSEA), which united environmentally minded high school students at a half-dozen schools in his area. Within three months, MCSEA had gathered over one thousand petition signatures urging the state legislature to protect the forest. The group then hand-delivered the petitions to state delegates, lobbied them on the issue, and helped organize a rally in the state capital. The coalition had been working on the issue for five years, and MCSEA proved instrumental in finally saving the forest. Legislators were surprised to see high school students so enthusiastic about the issue, and that made a real difference in the final decision.

“It was only because we connected ourselves to the larger environmental community and asked ‘how can we help?’ that we were able to achieve victory.” -- Dave Karpf

Dave took his experience with MCSEA and went on to direct the Sierra Student Coalition, training hundreds of other students to run campaigns on a variety of issues. Like Dave, you can start your environmental activism by locating a community of like-minded individuals already working on environmental issues on your campus, online, or in your community. Find out what these groups are working on, then figure out how you can help them build their power. Later, after you’ve built relationships with these group members and achieved victory on the hot issues, suggest that they tackle your passion as their next project. Organizing is a community activity, and we’re almost never starting from scratch.

If you haven’t yet decided which issue you want to work for, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with being involved in many issues. In fact, that can be a great way to get educated about a range of causes and get a taste for many different forms of activism. If you’re just getting started, I highly recommend exploring everything and anything that calls out to you. That’s what citizen activism is all about: expressing your values and your beliefs.

However, many young activists spread themselves too thin. The more issues you work on, the less likely you are to make a meaningful difference in any one arena. The most successful individuals and groups tend to focus on one or two main issues and relentlessly campaign until they win. Once you’ve found an issue that you’re really passionate about, try to use the 80-20 rule (an idea that we activists have adopted from the business world): spend 80 percent of your time, energy, and resources working on that issue, and use the remaining 20 percent to explore other issues that you feel passionate about.

If you’re still looking for your cause, here are a handful of the most pressing environmental challenges of the twenty-first century and related topics within each area:

Climate change and energy production (global warming, energy conservation, renewable energy production, fossil fuel use, nuclear energy and waste, mountaintop coal mining)

Waste creation (electronic waste, landfills, recycling, composting, incineration)

Toxins and pollution (air and water pollution, acid rain, oil spills, smog, pesticides and herbicides, carcinogens, heavy metals)

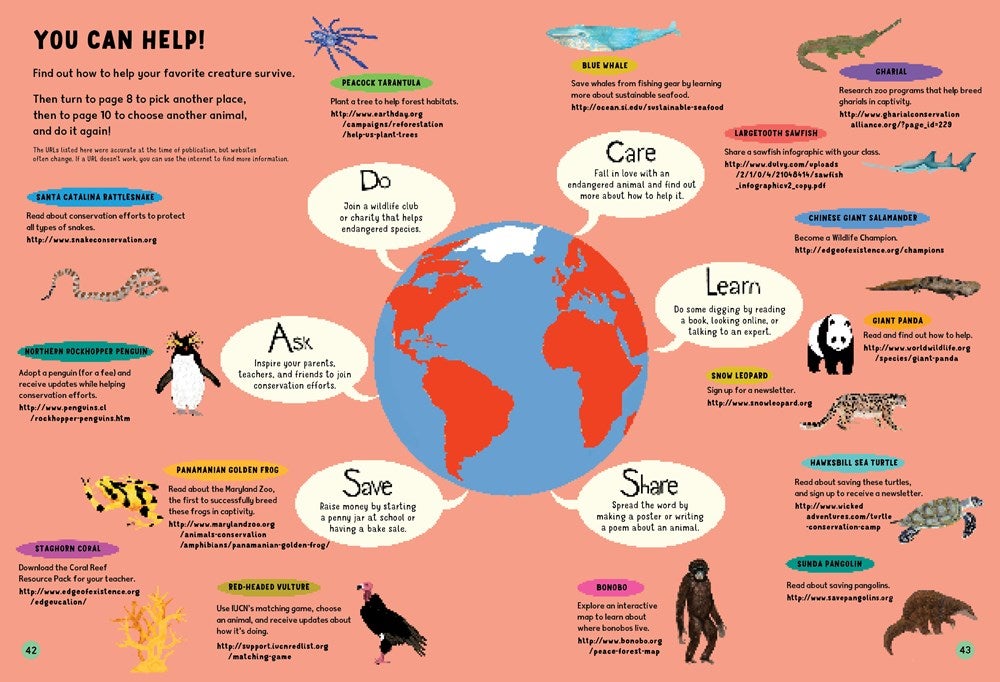

Land and species conservation (restoration of degraded ecosystems, species extinction, public lands preservation and access, wilderness areas, deforestation, illegal logging and poaching)

Urban planning (sprawl, urban renewal, green building, population growth)

Agriculture and food (organic and local foods, urban gardens, monoculture farming, meat production, grazing, desertification, soil conservation, genetically modified foods)

Water resources (dams, drinking water, privatization of water resources)

Ocean conservation (overfishing, shark finning, whaling, ocean dumping, ocean acidification)

Animal rights (factory farms, animals as food and clothing, hunting and trapping)

Public education (consumerism, environmental education)

Groups like the Sierra Club (www.sierraclub.org), Greenpeace (www.greenpeace.org), and Friends of the Earth (www.foe.org) offer information about a number of the topics just listed. Read background information, watch videos, and research case studies of areas under threat and pressing issues until you find one that calls out to you.

Probably the best way to get a read on the environmental movement is to check out the major youth networks. The groups listed at the end of this chapter are all uniting to create change on a series of campaigns. If you’re not ready to design your own campaign or launch your own group, or you like the idea of working on large-scale environmental campaigns (too big for a local group to do alone), team up with one of these existing youth networks to make change collectively.

GET EDUCATED Once you have found your cause, it’s time to get educated.

Research is critical; you need to get rooted in your issue before launching full-steam ahead into action. It’s one thing to go out and “do good,” but by whose standards are you doing good and to what end? While there is always more to learn about an issue, and you don’t want to get stuck in the research stage, spend some time learning about the issue to provide a solid foundation for your future organizing. With a little bit of research, you’ll be better prepared to launch a strategic and useful action plan, without stepping on anybody’s toes. You don’t want to burst onto the scene without realizing there’s another local group in town that’s been working on your issue for five years (and knows what has worked, and what hasn’t, over that time).

To find out more about your issue of choice, watch documentary films, read newspaper articles and excerpts from books, and do extensive internet research. Ask your friends and family what they know about the topic. If you are working on a local issue, start having conversations with the people who are directly affected. You can do formal surveys or simply start up friendly conversations to learn from the people who know the subject most intimately. Who else is working on this issue on your campus, in your community, and beyond? Find out how those groups are addressing the matter. Then you can decide to either join up with existing efforts or launch your own new group to tackle the issue.

If you can’t find a local organization that is doing the kind of work you are interested in, your best bet might be to start your own group. Before starting a new group, however, make sure you actually need one. Start by finding out the history of environmental organizations on your campus or in your community. Have previous groups gone dormant? If so, why? What teachers or civic leaders have supported environmental and progressive projects? What organizations currently do progressive work on campus or in your town? Who are the key leaders in those groups? Are there community groups tackling your issue that would welcome a youth presence?

If you find a group with a similar mission, consider joining—perhaps you can create a new subcommittee or project group to work on your issue. Launching a group from scratch can be a lot of work, and there’s no need to reinvent the wheel if another group has made some headway. However, if a similar group doesn’t exist, or you’re not drawn to the people or issues covered by existing groups, then it could be time to launch your own.

NEXT STOP: CREATE AN ACTION PLAN Whether you launch a new group or join an existing one, one of the most valuable skills you can bring to the table is strategic planning. In the next chapter, I’ll show you how to develop a thoughtful and achievable action plan.

RESOURCES Energy Action Coalition, www.energyactioncoalition.org Launched in part by a former Brower Youth Award recipient and with numerous past recipients in leadership roles, the Energy Action Coalition is easily one of the most powerful student networks in North America. With fifty partner organizations, the coalition unites young people to fight for and win clean energy and climate policies on their campuses, while demanding that governments and corporations do the same.

Roots & Shoots, www.rootsandshoots.org Roots & Shoots, founded by renowned primatologist Dr. Jane Goodall, works with tens of thousands of young people in nearly one hundred countries to implement successful community service projects and global campaigns. Roots & Shoots focuses on wildlife, as well as the environment and people-centered programming.

Sierra Student Coalition (SSC), www.ssc.org SSC is the student-run arm of the Sierra Club and has produced more than ten Brower Youth Award winners. With a presence on over 250 campuses across the country, SSC provides great support, training, and resources, including fellowships for college and university students. Earth Island Institute founder David Brower was the primary architect of the Sierra Club’s lobbying and political efforts as the club’s first executive director from 1952–69.

Sierra Youth Coalition, www.syc-cjs.org The Sierra Youth Coalition is SSC’s counterpart in Canada, operating in eighty colleges and universities and fifty high schools.

Student Environmental Action Coalition (SEAC), www.seac.org SEAC, a loose and nonhierarchical student-run national network of students and campus environmental groups (mostly college, some high schools), champions environmental justice campaigns at the local and national level.

Student Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs), www.studentpirgs.org For more than forty years, the PIRGs have been working on environmental protection and consumer advocacy at university campuses across the United States. They offer students the skills and opportunity to investigate big social problems, come up with practical solutions, convince the media and public to pay attention, and get decision makers to act.

Copyright © 2011 by Sharon J. Smith. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.