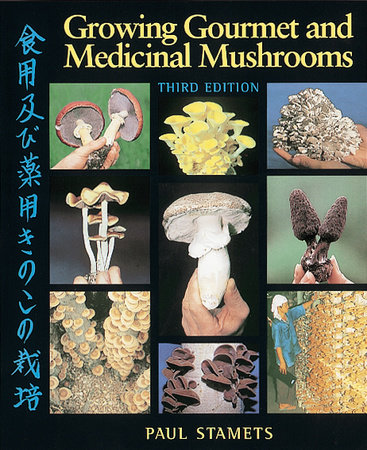

A detailed and comprehensive guide for growing and using gourmet and medicinal mushrooms commercially or at home.

“Absolutely the best book in the world on how to grow diverse and delicious mushrooms.”—David Arora, author of Mushrooms Demystified

With precise growth parameters for thirty-one mushroom species, this bible of mushroom cultivation includes gardening tips, state-of-the-art production techniques, realistic advice for laboratory and growing room construction, tasty mushroom recipes, and an invaluable troubleshooting guide.

More than 500 photographs, illustrations, and charts clearly identify each stage of cultivation, and a twenty-four-page color insert spotlights the intense beauty of various mushroom species. Whether you’re an ecologist, a chef, a forager, a pharmacologist, a commercial grower, or a home gardener—this indispensable handbook will get you started, help your garden succeed, and make your mycological landscapes the envy of the neighborhood.

“Absolutely the best book in the world on how to grow diverse and delicious mushrooms.”—David Arora, author of Mushrooms Demystified

With precise growth parameters for thirty-one mushroom species, this bible of mushroom cultivation includes gardening tips, state-of-the-art production techniques, realistic advice for laboratory and growing room construction, tasty mushroom recipes, and an invaluable troubleshooting guide.

More than 500 photographs, illustrations, and charts clearly identify each stage of cultivation, and a twenty-four-page color insert spotlights the intense beauty of various mushroom species. Whether you’re an ecologist, a chef, a forager, a pharmacologist, a commercial grower, or a home gardener—this indispensable handbook will get you started, help your garden succeed, and make your mycological landscapes the envy of the neighborhood.

“The most comprehensive manual of mushroom cultivation ever—filled with readable, useful informationabout every known mushroom species that people esteem for food and for medicine. Expanded, improved, and destined to be a classic.”—Dr. Andrew Weil, author of Spontaneous Healine and 8 Weeks to Optimum Health

Introduction

Mushrooms have never ceased to amaze me. The more I study them, the more I realize how little I have known, and how much more there is to learn. For thousands of years, fungi have evoked a host of responses from people—from fear and loathing to reverent adulation. And I am no exception.

When I was a little boy, wild mushrooms were looked upon with foreboding. It was not as if my parents were afraid of them, but our Irish heritage lacked a tradition of teaching children anything nice about mushrooms. In this peculiar climate of ignorance, rains fell and mushrooms magically sprang forth, wilted in the sun, rotted, and vanished without a trace. Given the scare stories told about “experts” dying after eating wild mushrooms, my family gave me the best advice they could: Stay away from all mushrooms, except those bought in the store. Naturally rebellious, I took this admonition as a challenge, a call to arms, firing up an already overactive imagination in a boy hungry for excitement.

When we were seven, my twin brother and I made a startling mycological discovery—Puffballs! We were told that they were not poisonous but if the spores got into our eyes, we would be instantly blinded! This information was quickly put to good use. We would viciously assault each other with mature puffballs, which would burst upon impact and emit a cloud of brown spores. The battle would continue until all the puffballs in sight had been hurled. They provided us with hours of delight over the years. Neither one of us ever went blind—although we both suffer from very poor eyesight. You must realize that to a seven-year-old these free, ready-made missiles satisfied instincts for warfare on the most primal of levels. This is my earliest memory of mushrooms, and to this day I consider it to be a positive emotional experience. (Although I admit a psychiatrist might like to explore these feelings in greater detail.)

Not until I became a teenager did my hunter-gatherer instincts resurface, when a relative returned from extensive travels in South America. With a twinkle in his eyes, he spoke of his experiences with the sacred Psilocybe mushrooms. I immediately set out to find these species, not in the jungles of Colombia, but in the fields and forests of Washington State where they were rumored to grow. For the first several years, my searches provided me with an abundance of excellent edible species, but no Psilocybes. Nevertheless, I was hooked.

When hiking through the mountains, I encountered so many mushrooms. Each was a mystery until I could match them with descriptions in a field guide. I soon came to learn that a mushroom was described as “edible,” “poisonous,” or my favorite, “unknown,” based on the experiences of others like me, who boldly ingested them. People are rarely neutral in their opinion about mushrooms—either they love them or they hate them. I took delight in striking fear into the hearts of the latter group, whose illogical distrust of fungi provoked my overactive imagination.

When I enrolled in the Evergreen State College in 1975, my skills at mushroom identification earned the support of a professor with similar interests. My initial interest was taxonomy, and I soon focused on fungal microscopy. The scanning electron microscope revealed new worlds, dimensional landscapes I never dreamed possible. As my interest grew, the need for fresh material year-round became essential. Naturally, these needs were aptly met by learning cultivation techniques, first in petri dishes, then on grain, and eventually on a wide variety of materials. In the quest for fresh specimens, I had embarked upon an irrevocable path that would steer my life on its current odyssey.

Mushrooms have never ceased to amaze me. The more I study them, the more I realize how little I have known, and how much more there is to learn. For thousands of years, fungi have evoked a host of responses from people—from fear and loathing to reverent adulation. And I am no exception.

When I was a little boy, wild mushrooms were looked upon with foreboding. It was not as if my parents were afraid of them, but our Irish heritage lacked a tradition of teaching children anything nice about mushrooms. In this peculiar climate of ignorance, rains fell and mushrooms magically sprang forth, wilted in the sun, rotted, and vanished without a trace. Given the scare stories told about “experts” dying after eating wild mushrooms, my family gave me the best advice they could: Stay away from all mushrooms, except those bought in the store. Naturally rebellious, I took this admonition as a challenge, a call to arms, firing up an already overactive imagination in a boy hungry for excitement.

When we were seven, my twin brother and I made a startling mycological discovery—Puffballs! We were told that they were not poisonous but if the spores got into our eyes, we would be instantly blinded! This information was quickly put to good use. We would viciously assault each other with mature puffballs, which would burst upon impact and emit a cloud of brown spores. The battle would continue until all the puffballs in sight had been hurled. They provided us with hours of delight over the years. Neither one of us ever went blind—although we both suffer from very poor eyesight. You must realize that to a seven-year-old these free, ready-made missiles satisfied instincts for warfare on the most primal of levels. This is my earliest memory of mushrooms, and to this day I consider it to be a positive emotional experience. (Although I admit a psychiatrist might like to explore these feelings in greater detail.)

Not until I became a teenager did my hunter-gatherer instincts resurface, when a relative returned from extensive travels in South America. With a twinkle in his eyes, he spoke of his experiences with the sacred Psilocybe mushrooms. I immediately set out to find these species, not in the jungles of Colombia, but in the fields and forests of Washington State where they were rumored to grow. For the first several years, my searches provided me with an abundance of excellent edible species, but no Psilocybes. Nevertheless, I was hooked.

When hiking through the mountains, I encountered so many mushrooms. Each was a mystery until I could match them with descriptions in a field guide. I soon came to learn that a mushroom was described as “edible,” “poisonous,” or my favorite, “unknown,” based on the experiences of others like me, who boldly ingested them. People are rarely neutral in their opinion about mushrooms—either they love them or they hate them. I took delight in striking fear into the hearts of the latter group, whose illogical distrust of fungi provoked my overactive imagination.

When I enrolled in the Evergreen State College in 1975, my skills at mushroom identification earned the support of a professor with similar interests. My initial interest was taxonomy, and I soon focused on fungal microscopy. The scanning electron microscope revealed new worlds, dimensional landscapes I never dreamed possible. As my interest grew, the need for fresh material year-round became essential. Naturally, these needs were aptly met by learning cultivation techniques, first in petri dishes, then on grain, and eventually on a wide variety of materials. In the quest for fresh specimens, I had embarked upon an irrevocable path that would steer my life on its current odyssey.

Copyright © 2000 by Paul Stamets. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

About

A detailed and comprehensive guide for growing and using gourmet and medicinal mushrooms commercially or at home.

“Absolutely the best book in the world on how to grow diverse and delicious mushrooms.”—David Arora, author of Mushrooms Demystified

With precise growth parameters for thirty-one mushroom species, this bible of mushroom cultivation includes gardening tips, state-of-the-art production techniques, realistic advice for laboratory and growing room construction, tasty mushroom recipes, and an invaluable troubleshooting guide.

More than 500 photographs, illustrations, and charts clearly identify each stage of cultivation, and a twenty-four-page color insert spotlights the intense beauty of various mushroom species. Whether you’re an ecologist, a chef, a forager, a pharmacologist, a commercial grower, or a home gardener—this indispensable handbook will get you started, help your garden succeed, and make your mycological landscapes the envy of the neighborhood.

“Absolutely the best book in the world on how to grow diverse and delicious mushrooms.”—David Arora, author of Mushrooms Demystified

With precise growth parameters for thirty-one mushroom species, this bible of mushroom cultivation includes gardening tips, state-of-the-art production techniques, realistic advice for laboratory and growing room construction, tasty mushroom recipes, and an invaluable troubleshooting guide.

More than 500 photographs, illustrations, and charts clearly identify each stage of cultivation, and a twenty-four-page color insert spotlights the intense beauty of various mushroom species. Whether you’re an ecologist, a chef, a forager, a pharmacologist, a commercial grower, or a home gardener—this indispensable handbook will get you started, help your garden succeed, and make your mycological landscapes the envy of the neighborhood.

Praise

“The most comprehensive manual of mushroom cultivation ever—filled with readable, useful informationabout every known mushroom species that people esteem for food and for medicine. Expanded, improved, and destined to be a classic.”—Dr. Andrew Weil, author of Spontaneous Healine and 8 Weeks to Optimum Health

Author

Excerpt

Introduction

Mushrooms have never ceased to amaze me. The more I study them, the more I realize how little I have known, and how much more there is to learn. For thousands of years, fungi have evoked a host of responses from people—from fear and loathing to reverent adulation. And I am no exception.

When I was a little boy, wild mushrooms were looked upon with foreboding. It was not as if my parents were afraid of them, but our Irish heritage lacked a tradition of teaching children anything nice about mushrooms. In this peculiar climate of ignorance, rains fell and mushrooms magically sprang forth, wilted in the sun, rotted, and vanished without a trace. Given the scare stories told about “experts” dying after eating wild mushrooms, my family gave me the best advice they could: Stay away from all mushrooms, except those bought in the store. Naturally rebellious, I took this admonition as a challenge, a call to arms, firing up an already overactive imagination in a boy hungry for excitement.

When we were seven, my twin brother and I made a startling mycological discovery—Puffballs! We were told that they were not poisonous but if the spores got into our eyes, we would be instantly blinded! This information was quickly put to good use. We would viciously assault each other with mature puffballs, which would burst upon impact and emit a cloud of brown spores. The battle would continue until all the puffballs in sight had been hurled. They provided us with hours of delight over the years. Neither one of us ever went blind—although we both suffer from very poor eyesight. You must realize that to a seven-year-old these free, ready-made missiles satisfied instincts for warfare on the most primal of levels. This is my earliest memory of mushrooms, and to this day I consider it to be a positive emotional experience. (Although I admit a psychiatrist might like to explore these feelings in greater detail.)

Not until I became a teenager did my hunter-gatherer instincts resurface, when a relative returned from extensive travels in South America. With a twinkle in his eyes, he spoke of his experiences with the sacred Psilocybe mushrooms. I immediately set out to find these species, not in the jungles of Colombia, but in the fields and forests of Washington State where they were rumored to grow. For the first several years, my searches provided me with an abundance of excellent edible species, but no Psilocybes. Nevertheless, I was hooked.

When hiking through the mountains, I encountered so many mushrooms. Each was a mystery until I could match them with descriptions in a field guide. I soon came to learn that a mushroom was described as “edible,” “poisonous,” or my favorite, “unknown,” based on the experiences of others like me, who boldly ingested them. People are rarely neutral in their opinion about mushrooms—either they love them or they hate them. I took delight in striking fear into the hearts of the latter group, whose illogical distrust of fungi provoked my overactive imagination.

When I enrolled in the Evergreen State College in 1975, my skills at mushroom identification earned the support of a professor with similar interests. My initial interest was taxonomy, and I soon focused on fungal microscopy. The scanning electron microscope revealed new worlds, dimensional landscapes I never dreamed possible. As my interest grew, the need for fresh material year-round became essential. Naturally, these needs were aptly met by learning cultivation techniques, first in petri dishes, then on grain, and eventually on a wide variety of materials. In the quest for fresh specimens, I had embarked upon an irrevocable path that would steer my life on its current odyssey.

Mushrooms have never ceased to amaze me. The more I study them, the more I realize how little I have known, and how much more there is to learn. For thousands of years, fungi have evoked a host of responses from people—from fear and loathing to reverent adulation. And I am no exception.

When I was a little boy, wild mushrooms were looked upon with foreboding. It was not as if my parents were afraid of them, but our Irish heritage lacked a tradition of teaching children anything nice about mushrooms. In this peculiar climate of ignorance, rains fell and mushrooms magically sprang forth, wilted in the sun, rotted, and vanished without a trace. Given the scare stories told about “experts” dying after eating wild mushrooms, my family gave me the best advice they could: Stay away from all mushrooms, except those bought in the store. Naturally rebellious, I took this admonition as a challenge, a call to arms, firing up an already overactive imagination in a boy hungry for excitement.

When we were seven, my twin brother and I made a startling mycological discovery—Puffballs! We were told that they were not poisonous but if the spores got into our eyes, we would be instantly blinded! This information was quickly put to good use. We would viciously assault each other with mature puffballs, which would burst upon impact and emit a cloud of brown spores. The battle would continue until all the puffballs in sight had been hurled. They provided us with hours of delight over the years. Neither one of us ever went blind—although we both suffer from very poor eyesight. You must realize that to a seven-year-old these free, ready-made missiles satisfied instincts for warfare on the most primal of levels. This is my earliest memory of mushrooms, and to this day I consider it to be a positive emotional experience. (Although I admit a psychiatrist might like to explore these feelings in greater detail.)

Not until I became a teenager did my hunter-gatherer instincts resurface, when a relative returned from extensive travels in South America. With a twinkle in his eyes, he spoke of his experiences with the sacred Psilocybe mushrooms. I immediately set out to find these species, not in the jungles of Colombia, but in the fields and forests of Washington State where they were rumored to grow. For the first several years, my searches provided me with an abundance of excellent edible species, but no Psilocybes. Nevertheless, I was hooked.

When hiking through the mountains, I encountered so many mushrooms. Each was a mystery until I could match them with descriptions in a field guide. I soon came to learn that a mushroom was described as “edible,” “poisonous,” or my favorite, “unknown,” based on the experiences of others like me, who boldly ingested them. People are rarely neutral in their opinion about mushrooms—either they love them or they hate them. I took delight in striking fear into the hearts of the latter group, whose illogical distrust of fungi provoked my overactive imagination.

When I enrolled in the Evergreen State College in 1975, my skills at mushroom identification earned the support of a professor with similar interests. My initial interest was taxonomy, and I soon focused on fungal microscopy. The scanning electron microscope revealed new worlds, dimensional landscapes I never dreamed possible. As my interest grew, the need for fresh material year-round became essential. Naturally, these needs were aptly met by learning cultivation techniques, first in petri dishes, then on grain, and eventually on a wide variety of materials. In the quest for fresh specimens, I had embarked upon an irrevocable path that would steer my life on its current odyssey.

Copyright © 2000 by Paul Stamets. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Back to Top

Notifications