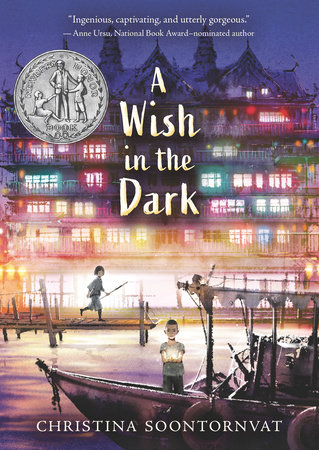

A 2021 Newbery Honor Book

A boy on the run. A girl determined to find him. A compelling fantasy looks at issues of privilege, protest, and justice.

All light in Chattana is created by one man — the Governor, who appeared after the Great Fire to bring peace and order to the city. For Pong, who was born in Namwon Prison, the magical lights represent freedom, and he dreams of the day he will be able to walk among them. But when Pong escapes from prison, he realizes that the world outside is no fairer than the one behind bars. The wealthy dine and dance under bright orb light, while the poor toil away in darkness. Worst of all, Pong’s prison tattoo marks him as a fugitive who can never be truly free.

Nok, the prison warden’s perfect daughter, is bent on tracking Pong down and restoring her family’s good name. But as Nok hunts Pong through the alleys and canals of Chattana, she uncovers secrets that make her question the truths she has always held dear. Set in a Thai-inspired fantasy world, Christina Soontornvat’s twist on Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables is a dazzling, fast-paced adventure that explores the difference between law and justice — and asks whether one child can shine a light in the dark.

A boy on the run. A girl determined to find him. A compelling fantasy looks at issues of privilege, protest, and justice.

All light in Chattana is created by one man — the Governor, who appeared after the Great Fire to bring peace and order to the city. For Pong, who was born in Namwon Prison, the magical lights represent freedom, and he dreams of the day he will be able to walk among them. But when Pong escapes from prison, he realizes that the world outside is no fairer than the one behind bars. The wealthy dine and dance under bright orb light, while the poor toil away in darkness. Worst of all, Pong’s prison tattoo marks him as a fugitive who can never be truly free.

Nok, the prison warden’s perfect daughter, is bent on tracking Pong down and restoring her family’s good name. But as Nok hunts Pong through the alleys and canals of Chattana, she uncovers secrets that make her question the truths she has always held dear. Set in a Thai-inspired fantasy world, Christina Soontornvat’s twist on Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables is a dazzling, fast-paced adventure that explores the difference between law and justice — and asks whether one child can shine a light in the dark.

-

HONOR

| 2021

Newbery Honor Book -

FINALIST

| 2020

Cybils -

AWARD

| 2020

Booklist Editor's Choice -

AWARD

| 2020

School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

It’s a novel—a stand- alone, no less—that seems to have it all: a sympathetic hero, a colorful setting, humor, heart, philosophy, and an epic conflict that relates the complexity and humanity of social justice without heavy-handed storytelling. Soontornvat deftly blends it all together, salting the tale with a dash of magic that enhances the underlying emotions in this masterfully paced adventure. An important book that not only shines a light but also shows young readers how to shine their own. Luminous.

—Booklist (starred review)

Set in a fantasy analogue of Thailand, all characters are presumed Thai, and Thai life and culture permeate the story in everything from the mangoes Pong eats in prison to the monks he meets beyond the prison's walls. It's also a retelling of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, and Soontornvat has maintained the themes of the original while making the plot and the characters utterly her own. Pong's and Nok's narratives are drawn together by common threads of family, loyalty, and a quest to define right and wrong, twining to create a single, satisfying tale. A complex, hopeful, fresh retelling.

—Kirkus Reviews

Soontornvat artfully builds up to a triumphant confrontation, weaving in important themes about oppression and civil disobedience along the way.

—Publishers Weekly

Nuanced questions of morality, oppression, and being defined by one’s circumstances are compounded with exciting action in this novel inspired by Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. The characters are resonant, and the action is enhanced by the fantastical Thailand-like setting. The original storyline and well-developed characters make this a standout novel. Highly recommended.

—School Library Journal

Combining themes of coming-of-age, protest, and the power of freedom, this book will inspire young readers to stand up for their own beliefs as well as those of all people. This is a thought-provoking adventure that will cause readers to ask themselves whether being safe or having freedom is the better option, and if that needs to be a choice at all.

—School Library Connection

The rich, atmospheric Thai-inspired settings ground Pong and Nok’s journeys toward self-understanding, from bleak Namwon to the peaceful temple Wat Singh to Chattana’s bustling, colorful Light Market...The novel offers satisfying meditations on moral choices as well as age-friendly openings into conversations about prison pipelines, autocracy, and socio-political action.

—Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Alternating between Pong's and Nok's stories, Soontornvat tells a satisfyingly intricate tale of escape and chase while raising questions about institutionalized injustices of privilege and want. Her Thai-inspired world is fully engaging, but perhaps most winning is the innocence, hope, and humor she conveys in the context of the struggle for social justice and with respect to the children's growth.

—The Horn Book

A thrilling fantasy, set in a fresh, original world, with a vital message at its heart. A Wish in the Dark is incandescent.

—Adam Gidwitz, Newbery Honor–winning author of The Inquisitor’s Tale

At once timeless and timely, Christina Soontornvat’s A Wish in the Dark is a richly imagined portrait of the power of hope, courage, and compassion to shine a light in dark times and the ability of small people to effect great change. Ingenious, captivating, and utterly gorgeous.

—Anne Ursu, National Book Award–nominated author of The Real Boy

Do you hear the people sing? Christina Soontornvat’s Les Misérables-inspired A Wish in the Dark will have readers cheering for Pong, the young boy who escapes a life of unfair imprisonment, discovers the powers of friendship and forgiveness, and raises his voice against oppression. I was swept away by the Thai setting, the Buddhist teachings of Father Cham, and the sheer grit and determination of these young characters. At the heart of this novel, like Victor Hugo’s, are the struggle for justice and the power of marginalized communities to change our world for the better. Young readers will be rooting for Pong and his band of revolutionary friends and inspired to spread more light in their own communities.

—Sayantani DasGupta, New York Times best-selling author of the Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond books

—Booklist (starred review)

Set in a fantasy analogue of Thailand, all characters are presumed Thai, and Thai life and culture permeate the story in everything from the mangoes Pong eats in prison to the monks he meets beyond the prison's walls. It's also a retelling of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, and Soontornvat has maintained the themes of the original while making the plot and the characters utterly her own. Pong's and Nok's narratives are drawn together by common threads of family, loyalty, and a quest to define right and wrong, twining to create a single, satisfying tale. A complex, hopeful, fresh retelling.

—Kirkus Reviews

Soontornvat artfully builds up to a triumphant confrontation, weaving in important themes about oppression and civil disobedience along the way.

—Publishers Weekly

Nuanced questions of morality, oppression, and being defined by one’s circumstances are compounded with exciting action in this novel inspired by Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. The characters are resonant, and the action is enhanced by the fantastical Thailand-like setting. The original storyline and well-developed characters make this a standout novel. Highly recommended.

—School Library Journal

Combining themes of coming-of-age, protest, and the power of freedom, this book will inspire young readers to stand up for their own beliefs as well as those of all people. This is a thought-provoking adventure that will cause readers to ask themselves whether being safe or having freedom is the better option, and if that needs to be a choice at all.

—School Library Connection

The rich, atmospheric Thai-inspired settings ground Pong and Nok’s journeys toward self-understanding, from bleak Namwon to the peaceful temple Wat Singh to Chattana’s bustling, colorful Light Market...The novel offers satisfying meditations on moral choices as well as age-friendly openings into conversations about prison pipelines, autocracy, and socio-political action.

—Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Alternating between Pong's and Nok's stories, Soontornvat tells a satisfyingly intricate tale of escape and chase while raising questions about institutionalized injustices of privilege and want. Her Thai-inspired world is fully engaging, but perhaps most winning is the innocence, hope, and humor she conveys in the context of the struggle for social justice and with respect to the children's growth.

—The Horn Book

A thrilling fantasy, set in a fresh, original world, with a vital message at its heart. A Wish in the Dark is incandescent.

—Adam Gidwitz, Newbery Honor–winning author of The Inquisitor’s Tale

At once timeless and timely, Christina Soontornvat’s A Wish in the Dark is a richly imagined portrait of the power of hope, courage, and compassion to shine a light in dark times and the ability of small people to effect great change. Ingenious, captivating, and utterly gorgeous.

—Anne Ursu, National Book Award–nominated author of The Real Boy

Do you hear the people sing? Christina Soontornvat’s Les Misérables-inspired A Wish in the Dark will have readers cheering for Pong, the young boy who escapes a life of unfair imprisonment, discovers the powers of friendship and forgiveness, and raises his voice against oppression. I was swept away by the Thai setting, the Buddhist teachings of Father Cham, and the sheer grit and determination of these young characters. At the heart of this novel, like Victor Hugo’s, are the struggle for justice and the power of marginalized communities to change our world for the better. Young readers will be rooting for Pong and his band of revolutionary friends and inspired to spread more light in their own communities.

—Sayantani DasGupta, New York Times best-selling author of the Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond books

Chapter 1

A monster of a mango tree grew in the courtyard of Namwon Prison. Its fluffy green branches stretched across the cracked cement and hung over the soupy brown water of the Chattana River. The women inmates spent most of their days sheltered under the shade of this tree while the boats glided up and down and up again on the other side of the prison gate.

The dozen children who lived in Namwon also spent most of their days lying in the shade. But not in mango season. In mango season, the tree dangled golden drops of heaven overhead, swaying just out of reach.

It drove the kids nuts.

They shouted at the mangoes. They chucked pieces of broken cement at them, trying to knock them down. And when the mangoes refused to fall, the children cried, stomped their bare feet, and collapsed in frustration on the ground.

Pong never joined them. Instead, he sat against the tree’s trunk, hands crossed behind his head. He looked like he was sleeping, but actually, he was paying attention.

Pong had been paying attention to the tree for weeks. He knew which mangoes had started ripening first. He noticed when the fruit lightened from lizard-skin green to pumpkin-rind yellow. He watched the ants crawl across the mangoes, and he knew where they paused to sniff the sugar inside.

Pong looked at his friend, Somkit, and gave him a short nod. Somkit wasn’t shouting at the mangoes, either. He was sitting under the branch that Pong had told him to sit under, waiting. Somkit had been waiting an hour, and he’d wait for hours more if he had to, because the most important thing to wait for in Namwon were the mangoes.

He and Pong were both nine years old, both orphans. Somkit was a head shorter than Pong, and skinny — even for a prisoner. He had a wide, round face, and the other kids teased him that he looked like those grilled rice balls on sticks that old ladies sold from their boats.

Like many of the women at Namwon, their mothers had been sent there because they’d been caught stealing. Both their mothers had died in childbirth, though from the stories the other women still told, Somkit’s birth had been more memorable and involved feet showing up where a head was supposed to be.

Pong wagged his finger at his friend to get him to scoot to the left.

A little more.

A little more.

There.

Finally, after all that waiting, Pong heard the soft pop of a mango stem. He gasped and smiled as the first mango of the season dropped straight into Somkit’s waiting arms.

But before Pong could join his friend and share their triumph, two older girls noticed what Somkit held in his hands.

“Hey, did you see that?” said one of the girls, propping herself up on her knobby elbows.

“Sure did,” said the other, cracking scab-covered knuckles. “Hey, Skin-and-Bones,” she called to Somkit. “What do you got for me today?”

“Uh‑oh,” said Somkit, cradling the mango in one hand and bracing himself to stand up with the other.

He was useless in a fight, which meant that everyone liked fighting him the most. And he couldn’t run more than a few steps without coughing, which meant the fights usually ended badly.

Pong turned toward the guards who were leaning against the wall behind him, looking almost as bored with life in Namwon as the prisoners were.

“Excuse me, ma’am,” said Pong, bowing to the first guard.

She sucked on her teeth and slowly lifted one eyebrow.

“Ma’am, it’s those girls,” said Pong. “I think they’re going to take —”

“And what do you want me to do about it?” she snapped. “You kids need to learn to take care of yourselves.”

The other guard snorted. “Might be good for you to get kicked around a little. Toughen you up.”

A hot, angry feeling fluttered inside Pong’s chest. Of course the guards wouldn’t help. When did they ever? He looked at the women prisoners. They stared back at him with flat, resigned eyes. They were far past caring about one miserable mango.

Pong turned away from them and hurried back to his friend. The girls approached Somkit slowly, savoring the coming brawl. “Quick, climb on,” he said, dropping to one knee.

“What?” said Somkit.

“Just get on!”

“Oh, man, I know how this is gonna turn out,” grumbled Somkit as he climbed onto Pong’s back, still clutching the mango.

Pong knew, too, but it couldn’t be helped. Because while Pong was better than anyone at paying attention, and almost as good as Somkit at waiting, he was terrible at ignoring when things weren’t fair.

And the most important thing to do in Namwon was to forget about life being fair.

“Where do you think you’re going?” asked the knobby-elbowed girl as she strode toward them.

“We caught this mango, fair and square,” said Pong, backing himself and Somkit away.

“You sure did,” said her scab-knuckled friend. “And if you hand it over right now, we’ll only punch you once each. Fair and square.”

“Just do it,” whispered Somkit. “It’s not worth —”

“You don’t deserve it just because you want it,” said Pong firmly. “And you’re not taking it from us.”

“Is that right?” said the girls.

“Oh, man.” Somkit sighed. “Here we go!”

The girls shrieked and Pong took off. They chased him as he galloped around and around the courtyard with Somkit clinging onto his back like a baby monkey.

“You can never just let things go!” Somkit shouted.

“We can’t . . . let them have it!” panted Pong. “It’s ours!” He dodged around clumps of smaller children, who watched gleefully, relieved not to be the ones about to get the life pummeled out of them.

“So what? A mango isn’t worth getting beat up over.” Somkit looked over his shoulder. “Go faster, man — they’re going to catch us!”

The guards leaning against the wall laughed as they watched the chase. “Go on, girls. Get ’em!” said one.

“Not yet, though,” said the other guard. “This is the best entertainment we’ve had all week!”

“I’m . . . getting . . . tired.” Pong huffed. “You better . . . eat that thing before I collapse!”

Warm mango juice dripped down the back of Pong’s neck as Somkit tore into the fruit with his teeth. “Oh, man. I was wrong. This is worth getting beat up over.” Somkit reached over his friend’s shoulder and stuck a plug of mango into the corner of Pong’s mouth.

It was ripe and sweet, not stringy yet. Paradise.

A monster of a mango tree grew in the courtyard of Namwon Prison. Its fluffy green branches stretched across the cracked cement and hung over the soupy brown water of the Chattana River. The women inmates spent most of their days sheltered under the shade of this tree while the boats glided up and down and up again on the other side of the prison gate.

The dozen children who lived in Namwon also spent most of their days lying in the shade. But not in mango season. In mango season, the tree dangled golden drops of heaven overhead, swaying just out of reach.

It drove the kids nuts.

They shouted at the mangoes. They chucked pieces of broken cement at them, trying to knock them down. And when the mangoes refused to fall, the children cried, stomped their bare feet, and collapsed in frustration on the ground.

Pong never joined them. Instead, he sat against the tree’s trunk, hands crossed behind his head. He looked like he was sleeping, but actually, he was paying attention.

Pong had been paying attention to the tree for weeks. He knew which mangoes had started ripening first. He noticed when the fruit lightened from lizard-skin green to pumpkin-rind yellow. He watched the ants crawl across the mangoes, and he knew where they paused to sniff the sugar inside.

Pong looked at his friend, Somkit, and gave him a short nod. Somkit wasn’t shouting at the mangoes, either. He was sitting under the branch that Pong had told him to sit under, waiting. Somkit had been waiting an hour, and he’d wait for hours more if he had to, because the most important thing to wait for in Namwon were the mangoes.

He and Pong were both nine years old, both orphans. Somkit was a head shorter than Pong, and skinny — even for a prisoner. He had a wide, round face, and the other kids teased him that he looked like those grilled rice balls on sticks that old ladies sold from their boats.

Like many of the women at Namwon, their mothers had been sent there because they’d been caught stealing. Both their mothers had died in childbirth, though from the stories the other women still told, Somkit’s birth had been more memorable and involved feet showing up where a head was supposed to be.

Pong wagged his finger at his friend to get him to scoot to the left.

A little more.

A little more.

There.

Finally, after all that waiting, Pong heard the soft pop of a mango stem. He gasped and smiled as the first mango of the season dropped straight into Somkit’s waiting arms.

But before Pong could join his friend and share their triumph, two older girls noticed what Somkit held in his hands.

“Hey, did you see that?” said one of the girls, propping herself up on her knobby elbows.

“Sure did,” said the other, cracking scab-covered knuckles. “Hey, Skin-and-Bones,” she called to Somkit. “What do you got for me today?”

“Uh‑oh,” said Somkit, cradling the mango in one hand and bracing himself to stand up with the other.

He was useless in a fight, which meant that everyone liked fighting him the most. And he couldn’t run more than a few steps without coughing, which meant the fights usually ended badly.

Pong turned toward the guards who were leaning against the wall behind him, looking almost as bored with life in Namwon as the prisoners were.

“Excuse me, ma’am,” said Pong, bowing to the first guard.

She sucked on her teeth and slowly lifted one eyebrow.

“Ma’am, it’s those girls,” said Pong. “I think they’re going to take —”

“And what do you want me to do about it?” she snapped. “You kids need to learn to take care of yourselves.”

The other guard snorted. “Might be good for you to get kicked around a little. Toughen you up.”

A hot, angry feeling fluttered inside Pong’s chest. Of course the guards wouldn’t help. When did they ever? He looked at the women prisoners. They stared back at him with flat, resigned eyes. They were far past caring about one miserable mango.

Pong turned away from them and hurried back to his friend. The girls approached Somkit slowly, savoring the coming brawl. “Quick, climb on,” he said, dropping to one knee.

“What?” said Somkit.

“Just get on!”

“Oh, man, I know how this is gonna turn out,” grumbled Somkit as he climbed onto Pong’s back, still clutching the mango.

Pong knew, too, but it couldn’t be helped. Because while Pong was better than anyone at paying attention, and almost as good as Somkit at waiting, he was terrible at ignoring when things weren’t fair.

And the most important thing to do in Namwon was to forget about life being fair.

“Where do you think you’re going?” asked the knobby-elbowed girl as she strode toward them.

“We caught this mango, fair and square,” said Pong, backing himself and Somkit away.

“You sure did,” said her scab-knuckled friend. “And if you hand it over right now, we’ll only punch you once each. Fair and square.”

“Just do it,” whispered Somkit. “It’s not worth —”

“You don’t deserve it just because you want it,” said Pong firmly. “And you’re not taking it from us.”

“Is that right?” said the girls.

“Oh, man.” Somkit sighed. “Here we go!”

The girls shrieked and Pong took off. They chased him as he galloped around and around the courtyard with Somkit clinging onto his back like a baby monkey.

“You can never just let things go!” Somkit shouted.

“We can’t . . . let them have it!” panted Pong. “It’s ours!” He dodged around clumps of smaller children, who watched gleefully, relieved not to be the ones about to get the life pummeled out of them.

“So what? A mango isn’t worth getting beat up over.” Somkit looked over his shoulder. “Go faster, man — they’re going to catch us!”

The guards leaning against the wall laughed as they watched the chase. “Go on, girls. Get ’em!” said one.

“Not yet, though,” said the other guard. “This is the best entertainment we’ve had all week!”

“I’m . . . getting . . . tired.” Pong huffed. “You better . . . eat that thing before I collapse!”

Warm mango juice dripped down the back of Pong’s neck as Somkit tore into the fruit with his teeth. “Oh, man. I was wrong. This is worth getting beat up over.” Somkit reached over his friend’s shoulder and stuck a plug of mango into the corner of Pong’s mouth.

It was ripe and sweet, not stringy yet. Paradise.

Copyright © 2020 by Christina Soontornvat. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

About

A 2021 Newbery Honor Book

A boy on the run. A girl determined to find him. A compelling fantasy looks at issues of privilege, protest, and justice.

All light in Chattana is created by one man — the Governor, who appeared after the Great Fire to bring peace and order to the city. For Pong, who was born in Namwon Prison, the magical lights represent freedom, and he dreams of the day he will be able to walk among them. But when Pong escapes from prison, he realizes that the world outside is no fairer than the one behind bars. The wealthy dine and dance under bright orb light, while the poor toil away in darkness. Worst of all, Pong’s prison tattoo marks him as a fugitive who can never be truly free.

Nok, the prison warden’s perfect daughter, is bent on tracking Pong down and restoring her family’s good name. But as Nok hunts Pong through the alleys and canals of Chattana, she uncovers secrets that make her question the truths she has always held dear. Set in a Thai-inspired fantasy world, Christina Soontornvat’s twist on Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables is a dazzling, fast-paced adventure that explores the difference between law and justice — and asks whether one child can shine a light in the dark.

A boy on the run. A girl determined to find him. A compelling fantasy looks at issues of privilege, protest, and justice.

All light in Chattana is created by one man — the Governor, who appeared after the Great Fire to bring peace and order to the city. For Pong, who was born in Namwon Prison, the magical lights represent freedom, and he dreams of the day he will be able to walk among them. But when Pong escapes from prison, he realizes that the world outside is no fairer than the one behind bars. The wealthy dine and dance under bright orb light, while the poor toil away in darkness. Worst of all, Pong’s prison tattoo marks him as a fugitive who can never be truly free.

Nok, the prison warden’s perfect daughter, is bent on tracking Pong down and restoring her family’s good name. But as Nok hunts Pong through the alleys and canals of Chattana, she uncovers secrets that make her question the truths she has always held dear. Set in a Thai-inspired fantasy world, Christina Soontornvat’s twist on Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables is a dazzling, fast-paced adventure that explores the difference between law and justice — and asks whether one child can shine a light in the dark.

Awards

-

HONOR

| 2021

Newbery Honor Book -

FINALIST

| 2020

Cybils -

AWARD

| 2020

Booklist Editor's Choice -

AWARD

| 2020

School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

Praise

It’s a novel—a stand- alone, no less—that seems to have it all: a sympathetic hero, a colorful setting, humor, heart, philosophy, and an epic conflict that relates the complexity and humanity of social justice without heavy-handed storytelling. Soontornvat deftly blends it all together, salting the tale with a dash of magic that enhances the underlying emotions in this masterfully paced adventure. An important book that not only shines a light but also shows young readers how to shine their own. Luminous.

—Booklist (starred review)

Set in a fantasy analogue of Thailand, all characters are presumed Thai, and Thai life and culture permeate the story in everything from the mangoes Pong eats in prison to the monks he meets beyond the prison's walls. It's also a retelling of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, and Soontornvat has maintained the themes of the original while making the plot and the characters utterly her own. Pong's and Nok's narratives are drawn together by common threads of family, loyalty, and a quest to define right and wrong, twining to create a single, satisfying tale. A complex, hopeful, fresh retelling.

—Kirkus Reviews

Soontornvat artfully builds up to a triumphant confrontation, weaving in important themes about oppression and civil disobedience along the way.

—Publishers Weekly

Nuanced questions of morality, oppression, and being defined by one’s circumstances are compounded with exciting action in this novel inspired by Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. The characters are resonant, and the action is enhanced by the fantastical Thailand-like setting. The original storyline and well-developed characters make this a standout novel. Highly recommended.

—School Library Journal

Combining themes of coming-of-age, protest, and the power of freedom, this book will inspire young readers to stand up for their own beliefs as well as those of all people. This is a thought-provoking adventure that will cause readers to ask themselves whether being safe or having freedom is the better option, and if that needs to be a choice at all.

—School Library Connection

The rich, atmospheric Thai-inspired settings ground Pong and Nok’s journeys toward self-understanding, from bleak Namwon to the peaceful temple Wat Singh to Chattana’s bustling, colorful Light Market...The novel offers satisfying meditations on moral choices as well as age-friendly openings into conversations about prison pipelines, autocracy, and socio-political action.

—Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Alternating between Pong's and Nok's stories, Soontornvat tells a satisfyingly intricate tale of escape and chase while raising questions about institutionalized injustices of privilege and want. Her Thai-inspired world is fully engaging, but perhaps most winning is the innocence, hope, and humor she conveys in the context of the struggle for social justice and with respect to the children's growth.

—The Horn Book

A thrilling fantasy, set in a fresh, original world, with a vital message at its heart. A Wish in the Dark is incandescent.

—Adam Gidwitz, Newbery Honor–winning author of The Inquisitor’s Tale

At once timeless and timely, Christina Soontornvat’s A Wish in the Dark is a richly imagined portrait of the power of hope, courage, and compassion to shine a light in dark times and the ability of small people to effect great change. Ingenious, captivating, and utterly gorgeous.

—Anne Ursu, National Book Award–nominated author of The Real Boy

Do you hear the people sing? Christina Soontornvat’s Les Misérables-inspired A Wish in the Dark will have readers cheering for Pong, the young boy who escapes a life of unfair imprisonment, discovers the powers of friendship and forgiveness, and raises his voice against oppression. I was swept away by the Thai setting, the Buddhist teachings of Father Cham, and the sheer grit and determination of these young characters. At the heart of this novel, like Victor Hugo’s, are the struggle for justice and the power of marginalized communities to change our world for the better. Young readers will be rooting for Pong and his band of revolutionary friends and inspired to spread more light in their own communities.

—Sayantani DasGupta, New York Times best-selling author of the Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond books

—Booklist (starred review)

Set in a fantasy analogue of Thailand, all characters are presumed Thai, and Thai life and culture permeate the story in everything from the mangoes Pong eats in prison to the monks he meets beyond the prison's walls. It's also a retelling of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, and Soontornvat has maintained the themes of the original while making the plot and the characters utterly her own. Pong's and Nok's narratives are drawn together by common threads of family, loyalty, and a quest to define right and wrong, twining to create a single, satisfying tale. A complex, hopeful, fresh retelling.

—Kirkus Reviews

Soontornvat artfully builds up to a triumphant confrontation, weaving in important themes about oppression and civil disobedience along the way.

—Publishers Weekly

Nuanced questions of morality, oppression, and being defined by one’s circumstances are compounded with exciting action in this novel inspired by Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. The characters are resonant, and the action is enhanced by the fantastical Thailand-like setting. The original storyline and well-developed characters make this a standout novel. Highly recommended.

—School Library Journal

Combining themes of coming-of-age, protest, and the power of freedom, this book will inspire young readers to stand up for their own beliefs as well as those of all people. This is a thought-provoking adventure that will cause readers to ask themselves whether being safe or having freedom is the better option, and if that needs to be a choice at all.

—School Library Connection

The rich, atmospheric Thai-inspired settings ground Pong and Nok’s journeys toward self-understanding, from bleak Namwon to the peaceful temple Wat Singh to Chattana’s bustling, colorful Light Market...The novel offers satisfying meditations on moral choices as well as age-friendly openings into conversations about prison pipelines, autocracy, and socio-political action.

—Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Alternating between Pong's and Nok's stories, Soontornvat tells a satisfyingly intricate tale of escape and chase while raising questions about institutionalized injustices of privilege and want. Her Thai-inspired world is fully engaging, but perhaps most winning is the innocence, hope, and humor she conveys in the context of the struggle for social justice and with respect to the children's growth.

—The Horn Book

A thrilling fantasy, set in a fresh, original world, with a vital message at its heart. A Wish in the Dark is incandescent.

—Adam Gidwitz, Newbery Honor–winning author of The Inquisitor’s Tale

At once timeless and timely, Christina Soontornvat’s A Wish in the Dark is a richly imagined portrait of the power of hope, courage, and compassion to shine a light in dark times and the ability of small people to effect great change. Ingenious, captivating, and utterly gorgeous.

—Anne Ursu, National Book Award–nominated author of The Real Boy

Do you hear the people sing? Christina Soontornvat’s Les Misérables-inspired A Wish in the Dark will have readers cheering for Pong, the young boy who escapes a life of unfair imprisonment, discovers the powers of friendship and forgiveness, and raises his voice against oppression. I was swept away by the Thai setting, the Buddhist teachings of Father Cham, and the sheer grit and determination of these young characters. At the heart of this novel, like Victor Hugo’s, are the struggle for justice and the power of marginalized communities to change our world for the better. Young readers will be rooting for Pong and his band of revolutionary friends and inspired to spread more light in their own communities.

—Sayantani DasGupta, New York Times best-selling author of the Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond books

Author

Excerpt

Chapter 1

A monster of a mango tree grew in the courtyard of Namwon Prison. Its fluffy green branches stretched across the cracked cement and hung over the soupy brown water of the Chattana River. The women inmates spent most of their days sheltered under the shade of this tree while the boats glided up and down and up again on the other side of the prison gate.

The dozen children who lived in Namwon also spent most of their days lying in the shade. But not in mango season. In mango season, the tree dangled golden drops of heaven overhead, swaying just out of reach.

It drove the kids nuts.

They shouted at the mangoes. They chucked pieces of broken cement at them, trying to knock them down. And when the mangoes refused to fall, the children cried, stomped their bare feet, and collapsed in frustration on the ground.

Pong never joined them. Instead, he sat against the tree’s trunk, hands crossed behind his head. He looked like he was sleeping, but actually, he was paying attention.

Pong had been paying attention to the tree for weeks. He knew which mangoes had started ripening first. He noticed when the fruit lightened from lizard-skin green to pumpkin-rind yellow. He watched the ants crawl across the mangoes, and he knew where they paused to sniff the sugar inside.

Pong looked at his friend, Somkit, and gave him a short nod. Somkit wasn’t shouting at the mangoes, either. He was sitting under the branch that Pong had told him to sit under, waiting. Somkit had been waiting an hour, and he’d wait for hours more if he had to, because the most important thing to wait for in Namwon were the mangoes.

He and Pong were both nine years old, both orphans. Somkit was a head shorter than Pong, and skinny — even for a prisoner. He had a wide, round face, and the other kids teased him that he looked like those grilled rice balls on sticks that old ladies sold from their boats.

Like many of the women at Namwon, their mothers had been sent there because they’d been caught stealing. Both their mothers had died in childbirth, though from the stories the other women still told, Somkit’s birth had been more memorable and involved feet showing up where a head was supposed to be.

Pong wagged his finger at his friend to get him to scoot to the left.

A little more.

A little more.

There.

Finally, after all that waiting, Pong heard the soft pop of a mango stem. He gasped and smiled as the first mango of the season dropped straight into Somkit’s waiting arms.

But before Pong could join his friend and share their triumph, two older girls noticed what Somkit held in his hands.

“Hey, did you see that?” said one of the girls, propping herself up on her knobby elbows.

“Sure did,” said the other, cracking scab-covered knuckles. “Hey, Skin-and-Bones,” she called to Somkit. “What do you got for me today?”

“Uh‑oh,” said Somkit, cradling the mango in one hand and bracing himself to stand up with the other.

He was useless in a fight, which meant that everyone liked fighting him the most. And he couldn’t run more than a few steps without coughing, which meant the fights usually ended badly.

Pong turned toward the guards who were leaning against the wall behind him, looking almost as bored with life in Namwon as the prisoners were.

“Excuse me, ma’am,” said Pong, bowing to the first guard.

She sucked on her teeth and slowly lifted one eyebrow.

“Ma’am, it’s those girls,” said Pong. “I think they’re going to take —”

“And what do you want me to do about it?” she snapped. “You kids need to learn to take care of yourselves.”

The other guard snorted. “Might be good for you to get kicked around a little. Toughen you up.”

A hot, angry feeling fluttered inside Pong’s chest. Of course the guards wouldn’t help. When did they ever? He looked at the women prisoners. They stared back at him with flat, resigned eyes. They were far past caring about one miserable mango.

Pong turned away from them and hurried back to his friend. The girls approached Somkit slowly, savoring the coming brawl. “Quick, climb on,” he said, dropping to one knee.

“What?” said Somkit.

“Just get on!”

“Oh, man, I know how this is gonna turn out,” grumbled Somkit as he climbed onto Pong’s back, still clutching the mango.

Pong knew, too, but it couldn’t be helped. Because while Pong was better than anyone at paying attention, and almost as good as Somkit at waiting, he was terrible at ignoring when things weren’t fair.

And the most important thing to do in Namwon was to forget about life being fair.

“Where do you think you’re going?” asked the knobby-elbowed girl as she strode toward them.

“We caught this mango, fair and square,” said Pong, backing himself and Somkit away.

“You sure did,” said her scab-knuckled friend. “And if you hand it over right now, we’ll only punch you once each. Fair and square.”

“Just do it,” whispered Somkit. “It’s not worth —”

“You don’t deserve it just because you want it,” said Pong firmly. “And you’re not taking it from us.”

“Is that right?” said the girls.

“Oh, man.” Somkit sighed. “Here we go!”

The girls shrieked and Pong took off. They chased him as he galloped around and around the courtyard with Somkit clinging onto his back like a baby monkey.

“You can never just let things go!” Somkit shouted.

“We can’t . . . let them have it!” panted Pong. “It’s ours!” He dodged around clumps of smaller children, who watched gleefully, relieved not to be the ones about to get the life pummeled out of them.

“So what? A mango isn’t worth getting beat up over.” Somkit looked over his shoulder. “Go faster, man — they’re going to catch us!”

The guards leaning against the wall laughed as they watched the chase. “Go on, girls. Get ’em!” said one.

“Not yet, though,” said the other guard. “This is the best entertainment we’ve had all week!”

“I’m . . . getting . . . tired.” Pong huffed. “You better . . . eat that thing before I collapse!”

Warm mango juice dripped down the back of Pong’s neck as Somkit tore into the fruit with his teeth. “Oh, man. I was wrong. This is worth getting beat up over.” Somkit reached over his friend’s shoulder and stuck a plug of mango into the corner of Pong’s mouth.

It was ripe and sweet, not stringy yet. Paradise.

A monster of a mango tree grew in the courtyard of Namwon Prison. Its fluffy green branches stretched across the cracked cement and hung over the soupy brown water of the Chattana River. The women inmates spent most of their days sheltered under the shade of this tree while the boats glided up and down and up again on the other side of the prison gate.

The dozen children who lived in Namwon also spent most of their days lying in the shade. But not in mango season. In mango season, the tree dangled golden drops of heaven overhead, swaying just out of reach.

It drove the kids nuts.

They shouted at the mangoes. They chucked pieces of broken cement at them, trying to knock them down. And when the mangoes refused to fall, the children cried, stomped their bare feet, and collapsed in frustration on the ground.

Pong never joined them. Instead, he sat against the tree’s trunk, hands crossed behind his head. He looked like he was sleeping, but actually, he was paying attention.

Pong had been paying attention to the tree for weeks. He knew which mangoes had started ripening first. He noticed when the fruit lightened from lizard-skin green to pumpkin-rind yellow. He watched the ants crawl across the mangoes, and he knew where they paused to sniff the sugar inside.

Pong looked at his friend, Somkit, and gave him a short nod. Somkit wasn’t shouting at the mangoes, either. He was sitting under the branch that Pong had told him to sit under, waiting. Somkit had been waiting an hour, and he’d wait for hours more if he had to, because the most important thing to wait for in Namwon were the mangoes.

He and Pong were both nine years old, both orphans. Somkit was a head shorter than Pong, and skinny — even for a prisoner. He had a wide, round face, and the other kids teased him that he looked like those grilled rice balls on sticks that old ladies sold from their boats.

Like many of the women at Namwon, their mothers had been sent there because they’d been caught stealing. Both their mothers had died in childbirth, though from the stories the other women still told, Somkit’s birth had been more memorable and involved feet showing up where a head was supposed to be.

Pong wagged his finger at his friend to get him to scoot to the left.

A little more.

A little more.

There.

Finally, after all that waiting, Pong heard the soft pop of a mango stem. He gasped and smiled as the first mango of the season dropped straight into Somkit’s waiting arms.

But before Pong could join his friend and share their triumph, two older girls noticed what Somkit held in his hands.

“Hey, did you see that?” said one of the girls, propping herself up on her knobby elbows.

“Sure did,” said the other, cracking scab-covered knuckles. “Hey, Skin-and-Bones,” she called to Somkit. “What do you got for me today?”

“Uh‑oh,” said Somkit, cradling the mango in one hand and bracing himself to stand up with the other.

He was useless in a fight, which meant that everyone liked fighting him the most. And he couldn’t run more than a few steps without coughing, which meant the fights usually ended badly.

Pong turned toward the guards who were leaning against the wall behind him, looking almost as bored with life in Namwon as the prisoners were.

“Excuse me, ma’am,” said Pong, bowing to the first guard.

She sucked on her teeth and slowly lifted one eyebrow.

“Ma’am, it’s those girls,” said Pong. “I think they’re going to take —”

“And what do you want me to do about it?” she snapped. “You kids need to learn to take care of yourselves.”

The other guard snorted. “Might be good for you to get kicked around a little. Toughen you up.”

A hot, angry feeling fluttered inside Pong’s chest. Of course the guards wouldn’t help. When did they ever? He looked at the women prisoners. They stared back at him with flat, resigned eyes. They were far past caring about one miserable mango.

Pong turned away from them and hurried back to his friend. The girls approached Somkit slowly, savoring the coming brawl. “Quick, climb on,” he said, dropping to one knee.

“What?” said Somkit.

“Just get on!”

“Oh, man, I know how this is gonna turn out,” grumbled Somkit as he climbed onto Pong’s back, still clutching the mango.

Pong knew, too, but it couldn’t be helped. Because while Pong was better than anyone at paying attention, and almost as good as Somkit at waiting, he was terrible at ignoring when things weren’t fair.

And the most important thing to do in Namwon was to forget about life being fair.

“Where do you think you’re going?” asked the knobby-elbowed girl as she strode toward them.

“We caught this mango, fair and square,” said Pong, backing himself and Somkit away.

“You sure did,” said her scab-knuckled friend. “And if you hand it over right now, we’ll only punch you once each. Fair and square.”

“Just do it,” whispered Somkit. “It’s not worth —”

“You don’t deserve it just because you want it,” said Pong firmly. “And you’re not taking it from us.”

“Is that right?” said the girls.

“Oh, man.” Somkit sighed. “Here we go!”

The girls shrieked and Pong took off. They chased him as he galloped around and around the courtyard with Somkit clinging onto his back like a baby monkey.

“You can never just let things go!” Somkit shouted.

“We can’t . . . let them have it!” panted Pong. “It’s ours!” He dodged around clumps of smaller children, who watched gleefully, relieved not to be the ones about to get the life pummeled out of them.

“So what? A mango isn’t worth getting beat up over.” Somkit looked over his shoulder. “Go faster, man — they’re going to catch us!”

The guards leaning against the wall laughed as they watched the chase. “Go on, girls. Get ’em!” said one.

“Not yet, though,” said the other guard. “This is the best entertainment we’ve had all week!”

“I’m . . . getting . . . tired.” Pong huffed. “You better . . . eat that thing before I collapse!”

Warm mango juice dripped down the back of Pong’s neck as Somkit tore into the fruit with his teeth. “Oh, man. I was wrong. This is worth getting beat up over.” Somkit reached over his friend’s shoulder and stuck a plug of mango into the corner of Pong’s mouth.

It was ripe and sweet, not stringy yet. Paradise.

Copyright © 2020 by Christina Soontornvat. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Back to Top

Notifications