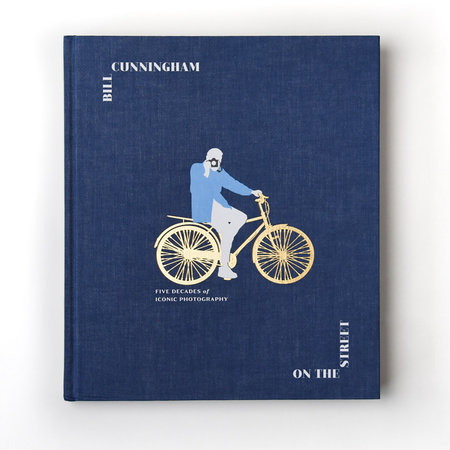

PREFACE

by TIINA LOITE, former photography editor,

The New York Times Styles section

Bill Cunningham was a photographer, yet he always liked to insist he wasn’t. “I’m not a real photographer,” he would say. “I’m a columnist who writes with pictures.”

I knew and worked with Bill for more than thirty years as a photo editor at

The New York Times. When I was asked to select and organize his work for this book, I did not kid myself about what that would involve. Bill worked seemingly around the clock, virtually every day of the year. My rough guess was that the number of photographs to research would equal the number on the national debt clock. As it turned out, I was pretty close.

I began in familiar territory, with the tens of thousands of pictures Bill took for

The Times, starting in the 1970s. This process was painstaking, months-long, and made more difficult by the paper’s database, which the years, moves, and human foibles had left incomplete. But to gain a full understanding of Bill’s range, it was important to look carefully at as many of the photos as were accessible, both those that had been published and those that had not.

And then there was Bill’s own personal archive, which is the fashion world’s equivalent of King Tut’s tomb. He kept this massive trove in his apartment, and after he died, it was transferred under the care of his niece, Trish Simonson, to an art-storage facility in Rockland County, just north of New York City. There, file cabinets and boxes—so numerous that forklifts are required to transfer them to a hangarlike room for viewing—overflow with prints, negatives, contact sheets, correspondence, clippings, notebooks, and more. Some drawers are so packed with files that they are nearly impenetrable.

What struck me most while searching through this remarkable material was that Bill was a man who absolutely loved his job. Was it even really a job? I think it was just Bill. More important, he understood the relevance of his work. The folders containing his negatives are also packed with layouts and absolutely every other piece of paper pertaining to that week’s column. When I looked at shots of blizzards from the 1970s, for example, he had noted how many inches of snow had fallen and how fast the wind was blowing. When I looked at the shots from a luncheon, even the printed menu and Bill’s phone message slips remained. All this supplemental material seemed to be more than notes to himself. I felt like it was there to benefit those who might look through this collection in the future, as I was now. Bill knew; Bill always knew.

He was famous for not spending much money on cameras—or bicycles, or clothing, or even file folders. Many of the “folders” in his cabinets were simply large envelopes that colleagues had discarded. When

The Times went digital and eliminated its photo lab, Bill continued to use film, taking it to a one-hour developer. He was encouraged to consider digital cameras, with colleagues even bringing technicians to the office to tutor him, but he would always mysteriously disappear when they arrived. Eventually, though, when the number of one-hour labs around the city dwindled, he finally surrendered.

So how to go about choosing what is to appear in this book? First, I had to accept that many wonderful images would be omitted—many of these images were missing and still I could have filled thousand-page volumes with what was available. Second, I knew that no matter what, some people would be upset by what is left out. Third, I tried to not have Bill be one of them.

His signature in his On the Street column in

The Times was a large number of small photographs illustrating a particular theme, which varied from issue to issue. He focused on the ensemble, or on a specific part of it, a hat perhaps, or a shoe. Bill also photographed things around the city to accent or accessorize his layouts—yellow daffodils to run alongside a layout of yellow clothing, for example. To him, the more pictures, the more densely packed the page, the better. He loved cropping, as seen at left, and shoehorning as many photos as he could into those layouts. It brought a look of mischievous glee to his face, even as he would then say, “This is all just filler around the ads, kids.”

But in looking at the totality of his photographs (or at least something relatively close to it), I found so many images that were wonderful just as they were, no cropping needed. The approach for this book was to let his photographs be photographs, so we see the trees for the forest. While photos of similar styles are still grouped together—reminiscent of the column—the reader can see how the images play off of one another, how they play off of images on the facing page. Many pages have only one photo on them (OK, Bill’s probably not happy). This book is not a collection of Bill’s columns. It is a collection of his photographs.

Because Bill Cunningham was a real photographer.

Copyright © 2019 by The New York Times Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.