Introduction

In the last decade, we’ve been talking a lot about “local” food.

Usually we’re talking about the source of the ingredients and their geographical proximity to your plate, but for me, the meaning is broader than that. To me, “local” is just as much about the people who live in my community, the people who inspire me and teach me and work with me, and how they like to cook and eat.

I’m lucky to live in Houston, Texas, which—this may surprise you—is by some measures the country’s most racially and ethnically diverse metropolis. In fact, the last census showed that there is no longer a “majority” in Houston. It’s a city of minorities. So for me, thinking about what it means to cook locally in Houston means going out into the different neighborhoods of my city and taking a census of my own: one of flavors, and of culinary traditions. I meet my fellow Houstonians, eat with them, learn how they cook, and then let those experiences inform my cooking. I try to tell stories through my food, stories that represent and reflect where we live.

Most of my favorite things to cook, many of which appear on the menus of my restaurants, are not dishes I grew up with. I wasn’t exposed to bánh mì or tamales until later in life. I grew up in a white middle-class family in Nebraska and Oklahoma, where food was always important. The dishes that my mom cooked fit easily into what is broadly considered (Anglo) “American food”: meatloaf and mashed potatoes, green beans stewed with pork, zucchini bread. To this day, I carry a torch for these dishes, and they are still a part of my cooking.

When I was in culinary school, and then a line cook coming up through the ranks, the ingredients and techniques that I had access to were pulled from Eurocentric cultures and cuisines. French food still held the crown as the “most important and best” cuisine in most cooking schools, and high-end restaurants at the time focused on versions of that same set of dishes. There were small cracks in the firmament, though, ones that piqued my curiosity. As a dishwasher at a sushi restaurant, I had my first taste of Japanese curry, served with scrambled eggs and rice, as a staff meal. I tried to understand the flavors at play in my orders of General Tso’s chicken.

Then I moved to Houston.

Working alongside Mexican-American line cooks, I learned about chiles—how to gauge their heat, how to use dried chiles versus fresh ones. And the late-night spot we all went to after work was a Vietnamese place where I had my first taste of fish sauce. At some point, I began to realize that my cooking, which was still drawing mostly from my culinary school and restaurant training, was happening in a vacuum and didn’t reflect the food that surrounded me. And I wanted to get out of that vacuum.

It started as simple curiosity. A friend would mention a great pho shop, and I’d go, order the first bowl listed on the menu, eat it, and leave. I got into it. I tracked down tips on new shops, and I explored their menus. Pretty quickly, these became the dishes I craved, dishes that became essential to my understanding of the place where I live. And I admit, my first instinct was to be proud of myself for “discovering” these spots—“I’m the guy with a bead on the best pho in Houston.” But I realized that there’s a distinction between “discovering” and

learning. Reality check: I wasn’t “discovering” anything because these communities and restaurants had been thriving long before I ever showed up. And when I

did go, and showed that I was there out of respect, curiosity, and a desire to learn, eating in restaurants became something more, something better: It was about making relationships. The food became more than delicious. It came to be about stories and the context of the people who were making these dishes, and their friendship and trust in letting me share their stories.

So I started going out as much as I could manage, and I started asking a lot of questions.

On a typical day off, I’d get in the car with a few friends and drive toward Bellaire, a sprawling neighborhood in Southwest Houston that has the highest concentration of Vietnamese businesses in the city. Or I’d head west, to H Mart, the giant Korean grocery store. Or north, to the Mexican restaurant El Hidalguense that roasts whole goats on spits in the dining room. And we’d eat. I’d start conversations with the servers, the cooks, the bussers, and the owners; we’d talk about Houston, how they arrived here, what they miss about the place they left. But the conversations always started with the food. I’d come back on another day, and we’d keep talking. Conversations about spices or the proper way to make a sauce opened the gate for more personal exchanges, ones that, in many cases, led to great friendships. More often than not, I’ve ended up in the kitchens of these restaurants, learning at the sides of these strangers who have become neighbors and friends. And they’ve ended up in the kitchens of my restaurants, or in our dining rooms for dinner.

These people have become my mentors, and Houston has proved to be the best culinary school I could ever hope to have.

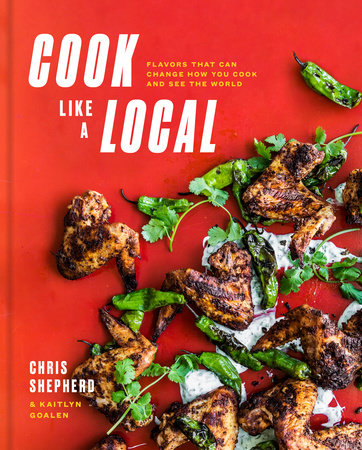

So now I’m writing this book to share some of the recipes that have been inspired by these experiences and connections, but also to encourage others to do the same. Reframe your idea of what your local food is by including the food of the people who live nearby, especially the people who may not look or sound like you.

Because here’s the thing: Houston’s diversity is not unique. Every city, and nearly every town, has its share of immigrant and cultural communities. Usually, they’re concentrated in specific neighborhoods. The food traditions of these communities are often kept within these neighborhoods as well, at a distance. They remain outliers, the food relegated to an “international” or “ethnic” label rather than viewed as what they are—as part of a regional cuisine.

And it’s not just restaurants but also ingredients. In chain supermarkets, there’s usually an “international” section, part of an aisle that has some Asian sauces, rice products, ready-to-eat curries, and seasonings. These are all grouped together, a whitewashed, Epcot-like pantry. To be fair, it’s getting better—these sections are growing slowly. But most immigrant neighborhoods have specialty grocery stores and markets where the ingredients to make their staple dishes aren’t ghetto-ized. I encourage you to expand your shopping options as well as your cooking horizons.

It’s time to address this blind spot in the world of restaurant chefs and glossy cookbooks. As a food-loving society, we’ve rediscovered the magic of eating and cooking based on what’s in season, so now it’s time to go a step further. Local food should reflect the people of a place, just as much as the ingredients of a place. Our eating experiences will be better for it, not to mention our empathy and understanding for those who are different from us.

It starts with a willingness to explore your surroundings. We’ll share the stories of some of the people who have influenced me and offer an approach to pushing past our culinary comfort zones.

This book is also about how to incorporate the techniques and ingredients from a spectrum of immigrant influences into your cooking rotation.

We’ll use ingredients as our entry point. This book is organized around pantry staples and seasonings, simple things that provide the flavor bases or foundations of whole cuisines. They all have long histories (some of them ancient), and their evolutions parallel the major migrations of human beings over centuries. They are also ingredients that aren’t necessarily featured in Anglo-American food traditions.

Each ingredient is a gateway to the stories, cooking styles, and relationships that have inspired my recipes.

Of course, I hope that by reading and cooking through each of these chapters, you’ll walk away with the tools and techniques to make things like corn, spices, and fish sauce sing in your kitchen. But I also hope you’ll leave with a hunger to head out on your own and fill your own pantry with ingredients you didn’t know you needed . . . but soon won’t want to live without.

Copyright © 2019 by Chris Shepherd and Kaitlyn Goalen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.