1

Entry into the Labyrinth Chaos Is Not Something You Improvise For almost twenty years I’ve been writing about Mexico City, a mélange of chronicles, essays, and personal memories. The juxtapositions the cityscape entails—the tire shop opposite the colonial church, the corporate skyscraper next to the taco stand—led me to create a hybrid genre, a natural response to an environment where the present is affected by stimuli from the pre-Hispanic world, the Viceroyalty, modern and postmodern culture. How many different times does Mexico City contain?

The area is so huge you might think it consists of different time zones. And at the outset of 2001, we were actually on the verge of creating more of them. The newly elected president Vicente Fox suggested inaugurating daylight savings time, but the head of the government of the then Federal District, Manuel López Obrador, refused to institute it. Since there are streets where the sidewalk on one side of the street is in Mexico City and the one opposite it is in the State of Mexico, the possibility of gaining or losing an hour by crossing the street became a possibility. The politicians stubbornly stuck to their chronological barriers until, unfortunately, the National Supreme Court declared it absurd to have two time zones. So we lost our chance to walk a few yards and pass from federal time to capital time.

In this valley of passions, space, like time, suffers variations, beginning with nomenclature. For decades, we used the term “Mexico City” to talk about the sixteen neighborhoods that made up the Federal District and the new zones annexed to it from the State of Mexico. The term was a handy shortcut, so linguistic academics advised writing the word city with a lower-case “c.” After 2016, the Federal District became Mexico City and acquired the same prerogatives held by the other states in the republic, but its name remained ambiguous because it does not include the entire metropolis (as did the moniker Mexico city) but only a part of it, which previously had been the Federal District. Welcome to the Valley of Anáhuac, where space and time converge!

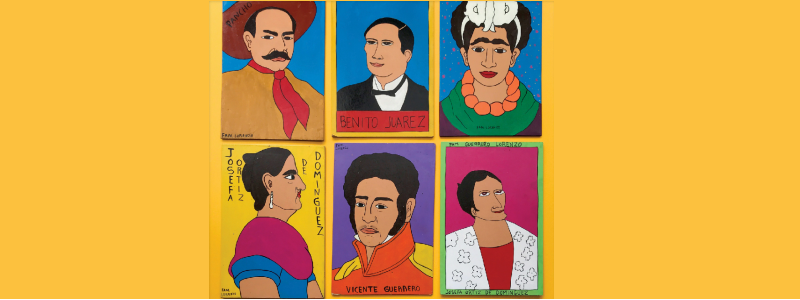

Syncretism has been our most helpful formula for creating a city. This is true in terms of both building and remembering it. The different generations of a single family turn the city into a palimpsest of memories, where grandmothers reveal hidden mysteries to their granddaughters.

Take, for example, the intersection called Central Axis (formerly San Juan de Letrán) and Madero in the heart of the capital. My paternal grandmother lived opposite the Alameda Central, and her generation’s idea of “modern” was the Palace of Fine Arts, that strange deployment of marble evocative of Ottoman fantasies. My generation associated it with a Las Vegas casino. For my mother, the modernity of that zone was embodied in the Lady Baltimore coffee shop, of European inspiration. For me, the outstanding sign of the times is the Latin American Tower, standing on that corner and built in the year I was born, 1956. Finally, for my daughter, the concept of the new is opposite the tower in Frikiplaza, a three-story commercial building dedicated to manga, anime, and other products of Japanese popular culture. So on that corner the “modernities” of four generations in my own family coexist. Instead of a single time and place, we live in the sum and juncture of different times and places, a codex simultaneously physical and one composed of memories of crossed destinies.

Without realizing I was beginning a book, I conceived the first of these texts in 1993, when I visited Berlin to present the German translation of

Argón’s Shot. Since my novel aspired to be a secret map of the Federal District, my publisher suggested I consult an issue of the magazine

Kursbuch because it contains an essay on Soviet city planning by the Russian-German philosopher Boris Groys: “The Metro as Utopia.” It was a revelation. To my surprise, the Soviet underground’s mirror image is our Collective Transport System.

The following year, I spent a semester at Yale University. I was guided by Groys’s essay and an anthology titled

Die Unwirklichkeit der Städte (The Unreality of Cities) compiled by Klaus R. Scherpe, that I found in the labyrinth of Sterling Memorial Library; the book, which tried to understand the city as a unitary discourse, inspired me to write an essay on the Mexican metro system. It was the beginning of a project that grew and changed over the course of years along with its theme and a plan that could accommodate its eventual expansion. Faced with the proliferation of pages, I came to realize that I didn’t need an editor so much as an urban planner.

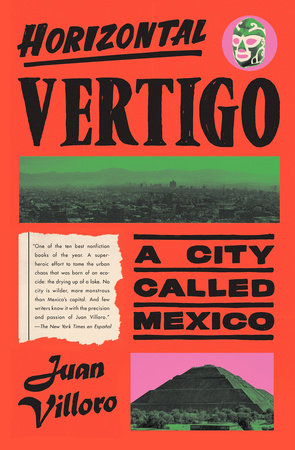

Horizontal Vertigo includes various kinds of testimonial devices. This book combines a multitude of genres, and, in a certain sense, it is various books. Structurally, it follows the criterion of

zapping. The episodes do not move forward in linear fashion, but, instead, follow the zigzagging of memory or the detours endemic to city traffic.

The reader may follow from beginning to end, or choose, like a

flâneur or a subway rider, the routes that interest him most: that of the characters, the places, the surprises, the ceremonies, the transitions, the personal stories (they’re all personal stories, but the sections gathered under the rubric “City Characters” emphasize that aspect).

Copyright © 2021 by Juan Villoro. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.