-

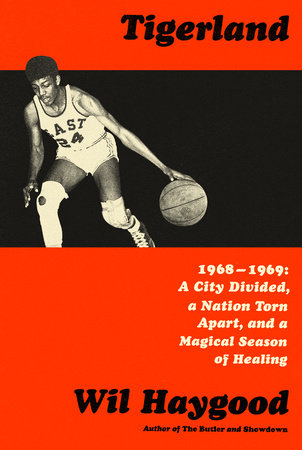

RUNNERUP

| 2019

Dayton Literary Peace Prize for Nonfiction

“As in all his avidly read books, Haygood sets the stories of fascinating individuals within the context of freshly reclaimed and vigorously recounted African American history as he masterfully brings a high school and its community to life. This laugh-and-cry tale of rollicking and wrenching drama set to the beat of thumping basketballs and the crack of baseball bats, fast breaks and cheerleaders’ chants, is electric with tension and conviction, and incandescent with unity and hope.” —Booklist (starred review)

“Mr. Haygood executes a series of historical fadeaway jump shots, taking us back for extended interludes with the likes of Rev. King, Jackie Robinson, federal Judge Bobby Duncan and other civil rights catalysts...the interludes illustrate the forward leaps, staggering setbacks and relentlessly hard work toward equality in America... And then we’re off on a classic sports story, as the school’s basketball and baseball players take form and the teams clamber to improbable heights. Naturally, Mr. Haygood explores the forces that shaped the young men, almost all of whom grew up in fatherless families with working mothers who struggled to feed and clothe them. Like J. Anthony Lukas’ Pulitzer Prize-winning 1985 book, “Common Ground” — also focused on school segregation — there’s complexity and ambiguity throughout.” —Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Haygood’s look at the socially turbulent atmosphere, told from the perspective of a black man coming of age at the time, is nationally relevant…it is a good story with uplifting moments of achievements by the players in spite of hardship and cultural turmoil.”

—The Columbus Dispatch

“’Tigerland’ is about more than sports. Sports provides a plot line and characters for a conversation about race in America. [Haygood's] research and careful descriptions of the athletes and community distinguish ‘Tigerland’ and give it humanity. ‘Tigerland’ maintains relevance today because it demands that we ask what, if anything, has been resolved.”

—StarTribune

“Here are the raw materials of a classic American story…vividly told. [Haygood] is a walker in the city with a memory like a lock box and a reporter’s notebook crammed with life lessons… a haunting, unforgettable book.”

—Wall Street Journal

Excerpted from Chapter Two:

Ollie Mae Walker and her husband, Charles, arrived in Columbus in 1948. Like many others, they had had enough of the South. They came as yet one more black family clutching battered suitcases and boxes of clothes and moving to the Poindexter Village housing projects. Charles worked as a janitor. There were eight Walker children. One day Charles announced he was leaving, going back to Georgia. His wife and children assumed something was wrong on his side of the family, or there was some kind of family business he had to attend to. But he left and never returned. Ollie Mae had to raise the children all alone. She worked as a maid at the Jefferson Hotel downtown, and after her husband abandoned the family, she asked her supervisor if she could start doubling up on her shifts. He often would let her, so some days she worked sixteen hours. All she seemed to care about was keeping her family together, under one roof.

When he was in the ninth grade at Champion Junior High, Larry Walker turned an ankle on the basketball court. The team trainer taped it and he returned to the court. But over the next few days the pain wouldn’t go away. At the hospital, X-rays were ordered, and they showed a tumor. “My mother worried it might be cancer. She didn’t know if they were going to cut a part of my leg off or what,” Walker recalls. He went into the hospital for surgery, a bone marrow graft. The tumor was non-malignant, but he lay in the hospital for a week. The welfare agency picked up the entire hospital bill. Every day his mother, Ollie Mae, would come gliding through the doorway of his hospital room, sometimes straight from a double shift.

Hart also prided himself on his bench talent, players whom he could use to spell the starters and insert into a game in strategic situations. He chose some savvy juniors who would accept their role playing. Kenny Mizelle—the oldest of nine children—was a gritty kid who lived in the Bolivar Arms housing project. He was a deft passer with Houdini-like hands, and nearly as fast as Larry Walker. Larry Mann, a junior forward, was smart and slithery around the basket and had a good basketball mind. Hal Thomas made the team as a sophomore.

Players who sat on Hart’s bench were often asked why they didn’t transfer to another school, with less fierce competition, where they might gain a starting position. And it came down to pride, to the old-fashioned joy—especially in the case of Robert Wright—of being on a team with a vaunted history, of playing and practicing alongside the likes of Nick Conner and Eddie Rat and now Bo-Pete Lamar. “We were precocious enough to understand who we were playing with,” recalls Robert Wright. “We knew it would be an honor to practice with these cats every day.”

Wright’s mother, Erma, was a domestic worker in the white suburb of Bexley. Sometimes she found herself on the same bus gliding down East Broad Street as teammate Kenny Mizelle’s mother, Mildred “Duckie” Mizelle, two black maids on their way to clean houses. Erma’s husband, Daniel, was a criminal and had spent time in the notorious Ohio State Penitentiary. “He told me he once killed a man,” Robert recalls. Daniel died when Robert was twelve years old. As a young boy, he figured he needed an extracurricular hobby to latch on to. He found it in basketball. When he reached East High, Bob Hart grew fond of Wright’s work habits and dependability.

Still, when the school doors opened in the fall of 1968, Robert Wright, like many of the East High students, remained rattled over the King assassination. “We were, for the first time in our lives, frightened,” he says of the entire East High student body. “We were used to white folks killing presidents. But Dr. King? We thought if they could kill King, they could kill any of us.” Wright also felt the impact of the protests that had taken place at the Olympics in Mexico City. “We saw what was going on with John Carlos and Tommie Smith. We understood the only way to escape the neighborhood was to play basketball, and play it well.” Wright also sensed a growing shift in sentiment among the student body: “We didn’t look at King with the same reverence as with H. Rap Brown or Stokely Carmichael. You now had cheerleaders at East who wouldn’t straighten their hair any longer,” he says, referring to the growing numbers who preferred to wear Afros.

So the Afros grew thicker, as did the inquiries about freedom and equal rights everywhere. It could be felt in the classrooms. Seniors at East had to take a course titled “Problems of Democracy.” (Everyone referred to it as POD.) The textbook was thick, its contents all about the challenges of government and governmental institutions. But many of the students now wanted to know exactly who was going to solve the ongoing problems of democracy right out there on the streets of Columbus, Ohio, and in Chicago, and in Indianapolis, and in Los Angeles—in all those places where riots and urban rebellion had taken place, and were still taking place. The students started insisting on conversations with their teachers about current events, about race and inequality. “I felt like I wanted to go out in the streets and throw rocks,” recalls David Reid. Reid, however, thought better: He was manager of the boys varsity basketball team.

Sometimes Bob Hart wished he could whip that term paper out he had written back in college about the travails of black people, and the need for the nation to face its flaws and demons. But his power now lay in coaching a group of black kids in a tough neighborhood.

His team assembled, and with a couple weeks of practice behind them, Hart scheduled a scrimmage with the East High Hi-Y team, those basketball players who had been deemed not good enough to make varsity. Because many of those players still nursed grudges about having been cut, Hart always relished the opportunity to show them the beauty of playing under control, with a ref’s whistle—the game skills he demanded of his varsity players.

Hart was playing coy with local reporters about announcing his starting lineup. His starting five would certainly come from among his top seven players. For the Hi-Y game he put a lineup of Conner, Hickman, Ratleff, Larry Walker, and newcomer Bo-Pete Lamar on the floor. The game was closed to the public. Some of the Hi-Y players were hyped up, figuring this would be a good time to show Hart he had made a mistake by cutting them. They were scrappy and fearless. As the game got under way, Hart could see it would take practice for Lamar to mesh with the rest of the players. There was the usual grunting and exhaustion, since the players from both teams were not yet in their best shape. But for all their prowess, Ratleff and Conner and Lamar and their teammates couldn’t keep up with the Hi-Y team. The Hi-Y team was winning. Their players began wolf whistling, taunting the varsity players. Hart stopped the game and decided that at the end of every quarter the clock would be stopped. When each new quarter began, the game clock would start over, the score zero to zero. “The rules changed when we were losing,” recalls varsity member Robert Wright.

“They beat us,” remembers varsity member Kenny Mizelle.

“We were working on some things,” Larry Walker says, going on to explain that correcting technique was more important to the team than a scrimmage that didn’t count.

The varsity players indeed brushed it all off, telling classmates the next day it was just a scrimmage, that they were not about to overly exert themselves and get hurt, especially against the Hi-Y team. They promised all who kept asking that they would be ready when the season opened.

If there was a facet of the game in which Bob Hart wanted his current team to improve, it was long-range shooting. His teams had always been thought of as overdependent on inside caginess and muscle. At the beginning of the 1968 season, Hart brought Scott Guiler onto his staff as an unpaid volunteer coach. Guiler was in graduate school at Ohio State University, and he was a shooter. At Canal Winchester High School, an all-white school located east of Columbus in farm country, he had been one of the best high school shooters in the school’s history. He possessed a picture-perfect jump shot. Were it not for a serious ankle injury in his senior year of high school, he would have gone on to play college basketball. Hart figured the jump shooters on his team—which mainly meant Bo-Pete Lamar—would benefit from just watching Guiler launch beautiful, high arching jump shots from all over the court. “Before practice,” Guiler recalls, “I’d play three-on-three with the players—me, Nick, Rat, Hickman, Bo-Pete, Coach Pennell. I really enjoyed that.” Bob Hart watched Guiler shoot and his Cheshire grin was hard to miss.

***

While he was sitting in a London prison awaiting extradition to America—and while the students of East High School in Columbus, Ohio, were demanding classroom time to discuss the King assassination—James Earl Ray was being hailed in some circles in America, namely by the Ku Klux Klan, and the Patriotic Legal Fund, the latter a crackpot mélange of undistinguished attorneys. Prison authorities at Wandsworth prison worried about Ray’s mental state and were on guard for suicide attempts. None occurred. “He just hated black people,” a prison guard who had befriended Ray would recall. “He said so on many occasions. He called them ‘niggers.’ In fact, he said he was going to Africa to shoot some more.” Alexander Eist, the prison guard, concluded that Ray might be insane. “I can raise a lot of money, write books, go on television,” Ray told him. “In parts of America, I’m a national hero.”

Back on American soil and in a heavily guarded cell in downtown Memphis, James Earl Ray confronted the overwhelming evidence against him. There was a good chance of a first-degree murder conviction, for which he might be executed in the electric chair. So Ray pleaded guilty in lieu of a jury trial and received a ninety-nine-year prison sentence. He soon told a feverish and fanciful story about the King killing to journalist William Bradford Huie, claiming that he had been a pawn in a conspiracy, that he personally didn’t pull the trigger. Huie was the perfect vehicle for such a tale. In his reporting career, Huie had seesawed between itinerant magazine reporting and giving lectures. He was a hustler of words and stories and storytelling. In 1955 he had covered the trial of the white men in Mississippi who had murdered fifteen-year-old Emmett Till for whistling at a white woman. The all-white Mississippi jury quickly acquitted the men. Huie then paid them $4,000 to tell him of their guilt. The men, realizing they could not be charged twice, took the money, told Huie of their murderous deed, and Huie wrote his story, forever becoming identified with “checkbook journalism.” Huie didn’t seem to mind the stigma. He certainly knew how to track and follow a good, dramatic story. Huie had covered the trial concerning the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, civil rights workers who were cut down by police officers and rogue associates on the night of June 21, 1964, in rural Mississippi. The local court acquitted the men, but they were eventually sentenced to prison on federal charges. Huie wrote the story in Three Lives for Mississippi, a book about the murders. While covering the civil rights movement, Huie had met Martin Luther King Jr. He was able to engage King to write an introduction to an edition of Three Lives for Mississippi. King was enamored of Huie’s interest in telling civil rights stories. Not long after that book’s publication, Huie was interviewing King’s assassin and writing a book about the murder. The King and James Earl Ray assassination story, in all its permutations, would appear in newspapers and magazines throughout the 1968–69 Tigers basketball team’s season.

About

Awards

-

RUNNERUP

| 2019

Dayton Literary Peace Prize for Nonfiction

Praise

“As in all his avidly read books, Haygood sets the stories of fascinating individuals within the context of freshly reclaimed and vigorously recounted African American history as he masterfully brings a high school and its community to life. This laugh-and-cry tale of rollicking and wrenching drama set to the beat of thumping basketballs and the crack of baseball bats, fast breaks and cheerleaders’ chants, is electric with tension and conviction, and incandescent with unity and hope.” —Booklist (starred review)

“Mr. Haygood executes a series of historical fadeaway jump shots, taking us back for extended interludes with the likes of Rev. King, Jackie Robinson, federal Judge Bobby Duncan and other civil rights catalysts...the interludes illustrate the forward leaps, staggering setbacks and relentlessly hard work toward equality in America... And then we’re off on a classic sports story, as the school’s basketball and baseball players take form and the teams clamber to improbable heights. Naturally, Mr. Haygood explores the forces that shaped the young men, almost all of whom grew up in fatherless families with working mothers who struggled to feed and clothe them. Like J. Anthony Lukas’ Pulitzer Prize-winning 1985 book, “Common Ground” — also focused on school segregation — there’s complexity and ambiguity throughout.” —Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Haygood’s look at the socially turbulent atmosphere, told from the perspective of a black man coming of age at the time, is nationally relevant…it is a good story with uplifting moments of achievements by the players in spite of hardship and cultural turmoil.”

—The Columbus Dispatch

“’Tigerland’ is about more than sports. Sports provides a plot line and characters for a conversation about race in America. [Haygood's] research and careful descriptions of the athletes and community distinguish ‘Tigerland’ and give it humanity. ‘Tigerland’ maintains relevance today because it demands that we ask what, if anything, has been resolved.”

—StarTribune

“Here are the raw materials of a classic American story…vividly told. [Haygood] is a walker in the city with a memory like a lock box and a reporter’s notebook crammed with life lessons… a haunting, unforgettable book.”

—Wall Street Journal

Author

Excerpt

Excerpted from Chapter Two:

Ollie Mae Walker and her husband, Charles, arrived in Columbus in 1948. Like many others, they had had enough of the South. They came as yet one more black family clutching battered suitcases and boxes of clothes and moving to the Poindexter Village housing projects. Charles worked as a janitor. There were eight Walker children. One day Charles announced he was leaving, going back to Georgia. His wife and children assumed something was wrong on his side of the family, or there was some kind of family business he had to attend to. But he left and never returned. Ollie Mae had to raise the children all alone. She worked as a maid at the Jefferson Hotel downtown, and after her husband abandoned the family, she asked her supervisor if she could start doubling up on her shifts. He often would let her, so some days she worked sixteen hours. All she seemed to care about was keeping her family together, under one roof.

When he was in the ninth grade at Champion Junior High, Larry Walker turned an ankle on the basketball court. The team trainer taped it and he returned to the court. But over the next few days the pain wouldn’t go away. At the hospital, X-rays were ordered, and they showed a tumor. “My mother worried it might be cancer. She didn’t know if they were going to cut a part of my leg off or what,” Walker recalls. He went into the hospital for surgery, a bone marrow graft. The tumor was non-malignant, but he lay in the hospital for a week. The welfare agency picked up the entire hospital bill. Every day his mother, Ollie Mae, would come gliding through the doorway of his hospital room, sometimes straight from a double shift.

Hart also prided himself on his bench talent, players whom he could use to spell the starters and insert into a game in strategic situations. He chose some savvy juniors who would accept their role playing. Kenny Mizelle—the oldest of nine children—was a gritty kid who lived in the Bolivar Arms housing project. He was a deft passer with Houdini-like hands, and nearly as fast as Larry Walker. Larry Mann, a junior forward, was smart and slithery around the basket and had a good basketball mind. Hal Thomas made the team as a sophomore.

Players who sat on Hart’s bench were often asked why they didn’t transfer to another school, with less fierce competition, where they might gain a starting position. And it came down to pride, to the old-fashioned joy—especially in the case of Robert Wright—of being on a team with a vaunted history, of playing and practicing alongside the likes of Nick Conner and Eddie Rat and now Bo-Pete Lamar. “We were precocious enough to understand who we were playing with,” recalls Robert Wright. “We knew it would be an honor to practice with these cats every day.”

Wright’s mother, Erma, was a domestic worker in the white suburb of Bexley. Sometimes she found herself on the same bus gliding down East Broad Street as teammate Kenny Mizelle’s mother, Mildred “Duckie” Mizelle, two black maids on their way to clean houses. Erma’s husband, Daniel, was a criminal and had spent time in the notorious Ohio State Penitentiary. “He told me he once killed a man,” Robert recalls. Daniel died when Robert was twelve years old. As a young boy, he figured he needed an extracurricular hobby to latch on to. He found it in basketball. When he reached East High, Bob Hart grew fond of Wright’s work habits and dependability.

Still, when the school doors opened in the fall of 1968, Robert Wright, like many of the East High students, remained rattled over the King assassination. “We were, for the first time in our lives, frightened,” he says of the entire East High student body. “We were used to white folks killing presidents. But Dr. King? We thought if they could kill King, they could kill any of us.” Wright also felt the impact of the protests that had taken place at the Olympics in Mexico City. “We saw what was going on with John Carlos and Tommie Smith. We understood the only way to escape the neighborhood was to play basketball, and play it well.” Wright also sensed a growing shift in sentiment among the student body: “We didn’t look at King with the same reverence as with H. Rap Brown or Stokely Carmichael. You now had cheerleaders at East who wouldn’t straighten their hair any longer,” he says, referring to the growing numbers who preferred to wear Afros.

So the Afros grew thicker, as did the inquiries about freedom and equal rights everywhere. It could be felt in the classrooms. Seniors at East had to take a course titled “Problems of Democracy.” (Everyone referred to it as POD.) The textbook was thick, its contents all about the challenges of government and governmental institutions. But many of the students now wanted to know exactly who was going to solve the ongoing problems of democracy right out there on the streets of Columbus, Ohio, and in Chicago, and in Indianapolis, and in Los Angeles—in all those places where riots and urban rebellion had taken place, and were still taking place. The students started insisting on conversations with their teachers about current events, about race and inequality. “I felt like I wanted to go out in the streets and throw rocks,” recalls David Reid. Reid, however, thought better: He was manager of the boys varsity basketball team.

Sometimes Bob Hart wished he could whip that term paper out he had written back in college about the travails of black people, and the need for the nation to face its flaws and demons. But his power now lay in coaching a group of black kids in a tough neighborhood.

His team assembled, and with a couple weeks of practice behind them, Hart scheduled a scrimmage with the East High Hi-Y team, those basketball players who had been deemed not good enough to make varsity. Because many of those players still nursed grudges about having been cut, Hart always relished the opportunity to show them the beauty of playing under control, with a ref’s whistle—the game skills he demanded of his varsity players.

Hart was playing coy with local reporters about announcing his starting lineup. His starting five would certainly come from among his top seven players. For the Hi-Y game he put a lineup of Conner, Hickman, Ratleff, Larry Walker, and newcomer Bo-Pete Lamar on the floor. The game was closed to the public. Some of the Hi-Y players were hyped up, figuring this would be a good time to show Hart he had made a mistake by cutting them. They were scrappy and fearless. As the game got under way, Hart could see it would take practice for Lamar to mesh with the rest of the players. There was the usual grunting and exhaustion, since the players from both teams were not yet in their best shape. But for all their prowess, Ratleff and Conner and Lamar and their teammates couldn’t keep up with the Hi-Y team. The Hi-Y team was winning. Their players began wolf whistling, taunting the varsity players. Hart stopped the game and decided that at the end of every quarter the clock would be stopped. When each new quarter began, the game clock would start over, the score zero to zero. “The rules changed when we were losing,” recalls varsity member Robert Wright.

“They beat us,” remembers varsity member Kenny Mizelle.

“We were working on some things,” Larry Walker says, going on to explain that correcting technique was more important to the team than a scrimmage that didn’t count.

The varsity players indeed brushed it all off, telling classmates the next day it was just a scrimmage, that they were not about to overly exert themselves and get hurt, especially against the Hi-Y team. They promised all who kept asking that they would be ready when the season opened.

If there was a facet of the game in which Bob Hart wanted his current team to improve, it was long-range shooting. His teams had always been thought of as overdependent on inside caginess and muscle. At the beginning of the 1968 season, Hart brought Scott Guiler onto his staff as an unpaid volunteer coach. Guiler was in graduate school at Ohio State University, and he was a shooter. At Canal Winchester High School, an all-white school located east of Columbus in farm country, he had been one of the best high school shooters in the school’s history. He possessed a picture-perfect jump shot. Were it not for a serious ankle injury in his senior year of high school, he would have gone on to play college basketball. Hart figured the jump shooters on his team—which mainly meant Bo-Pete Lamar—would benefit from just watching Guiler launch beautiful, high arching jump shots from all over the court. “Before practice,” Guiler recalls, “I’d play three-on-three with the players—me, Nick, Rat, Hickman, Bo-Pete, Coach Pennell. I really enjoyed that.” Bob Hart watched Guiler shoot and his Cheshire grin was hard to miss.

***

While he was sitting in a London prison awaiting extradition to America—and while the students of East High School in Columbus, Ohio, were demanding classroom time to discuss the King assassination—James Earl Ray was being hailed in some circles in America, namely by the Ku Klux Klan, and the Patriotic Legal Fund, the latter a crackpot mélange of undistinguished attorneys. Prison authorities at Wandsworth prison worried about Ray’s mental state and were on guard for suicide attempts. None occurred. “He just hated black people,” a prison guard who had befriended Ray would recall. “He said so on many occasions. He called them ‘niggers.’ In fact, he said he was going to Africa to shoot some more.” Alexander Eist, the prison guard, concluded that Ray might be insane. “I can raise a lot of money, write books, go on television,” Ray told him. “In parts of America, I’m a national hero.”

Back on American soil and in a heavily guarded cell in downtown Memphis, James Earl Ray confronted the overwhelming evidence against him. There was a good chance of a first-degree murder conviction, for which he might be executed in the electric chair. So Ray pleaded guilty in lieu of a jury trial and received a ninety-nine-year prison sentence. He soon told a feverish and fanciful story about the King killing to journalist William Bradford Huie, claiming that he had been a pawn in a conspiracy, that he personally didn’t pull the trigger. Huie was the perfect vehicle for such a tale. In his reporting career, Huie had seesawed between itinerant magazine reporting and giving lectures. He was a hustler of words and stories and storytelling. In 1955 he had covered the trial of the white men in Mississippi who had murdered fifteen-year-old Emmett Till for whistling at a white woman. The all-white Mississippi jury quickly acquitted the men. Huie then paid them $4,000 to tell him of their guilt. The men, realizing they could not be charged twice, took the money, told Huie of their murderous deed, and Huie wrote his story, forever becoming identified with “checkbook journalism.” Huie didn’t seem to mind the stigma. He certainly knew how to track and follow a good, dramatic story. Huie had covered the trial concerning the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, civil rights workers who were cut down by police officers and rogue associates on the night of June 21, 1964, in rural Mississippi. The local court acquitted the men, but they were eventually sentenced to prison on federal charges. Huie wrote the story in Three Lives for Mississippi, a book about the murders. While covering the civil rights movement, Huie had met Martin Luther King Jr. He was able to engage King to write an introduction to an edition of Three Lives for Mississippi. King was enamored of Huie’s interest in telling civil rights stories. Not long after that book’s publication, Huie was interviewing King’s assassin and writing a book about the murder. The King and James Earl Ray assassination story, in all its permutations, would appear in newspapers and magazines throughout the 1968–69 Tigers basketball team’s season.

Notifications