INTRODUCTION

“Can I ask you a question?”

I’ve become accustomed to hearing this from people who have just been introduced to me. I usually beat them to the punch by replying, “Yes, I’m related to the store.” And to their inevitable follow-up query, I answer, “It was started by my grandparents in 1934.”

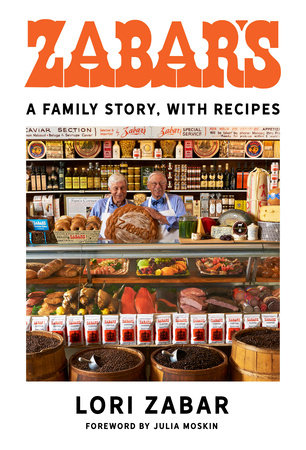

No matter how often I experience this exchange, the interest in my family’s business is always gratifying. These people know Zabar’s as one of the world’s greatest gourmet food stores, celebrated in books, in films, and on television, but they are amazed to learn that it has been at its original Broadway location for more than eighty-five years and that it is still being run by the same family who founded it—something that is quite unusual in today’s big-business environment.

My paternal grandparents, Lillian Teitelbaum and Louis (pronounced Louie) Zabar, fled the pogroms and unrest in Russia before they were a couple and arrived in the United States in 1921 and 1922, respectively. With little but willpower and a keen business sense, they built a retail food business that eventually consisted of Zabar’s and four grocery stores, all located along Broadway on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, from 80th Street to 110th Street. When my grandfather died in 1950 at the age of forty-nine, the businesses were taken over by his older sons—my uncle Saul and my father, Stanley—along with their eventual partner, Murray Klein. Together, the trio developed the company’s offerings and its real estate until Zabar’s was not only an iconic food store on the Upper West Side but also one of the most famous delicatessens in the world. Zabar’s is a cultural landmark and a vestige of Old New York that has survived nearly a century of transformation. You can’t miss that four-story, white-stucco, and brown-wood gabled Tudor-style structure that takes up half a city block, and the store’s classic bright orange banner.

Every day, thousands of loyal local customers and tourists from across America and all over the world stream into the store for their weekly roast of fresh coffee; for a yeasty chocolate babka or tender, raisin-filled rugelach; for flaky potato knishes or blintzes plump with fruit; for cheeses of all kinds; and, on weekends, for Zabar’s legendary New York bagels with nova and a schmear. Some keep coming back because they love the store’s chaotic energy or because the food reminds them of their childhood fare. Others have purposely moved to the neighborhood because of its “PTZ” (proximity to Zabar’s).

Like many of these customers, I’m also an Upper West Sider who pushes her cart through the store’s narrow, jam-packed aisles several times a week. Customers have their own rituals for shopping at Zabar’s, and here is mine.

My first stop is often just inside the store, at the bins of glistening olives—ebony, brown, and green—from France, Italy, Greece, Tunisia, Morocco, and beyond. I fill a container with my selections: intensely salty, wrinkled ebony Nyons; meaty, mild Cerignolas as large as golf balls; and my personal favorite, the petite and piquant French pitted Niçoise. Most people nibble them with a glass of wine before dinner, but I like to toss them into a mixed salad.

Next, I head to the staggering cheese selection. On my right, behind a serviced counter that extends nearly three yards, is a wall of hard cheeses—wheels of nutty Irish Cheddar, buttery Spanish Manchego, and sweeter Grana Padano. In the display case in front of the counter are the softer cheeses, dozens of them, mostly French and some Spanish, English, and American, cut into wedges large and small. Opposite the counter, on long steel racks, is a multitude of packaged and precut cheeses of various nationalities.

If I need guidance, I seek out Olga Dominguez, the department manager, who comes from the Dominican Republic and has been at the store since 1972. Olga’s best guess is that there are more than one thousand cheeses for sale at Zabar’s, the most popular being goat cheeses and alpine cheeses such as Swiss and Gruyère. Among my favorites are Oma, a pungent and sweet washed-rind cheese made from organic milk produced by the von Trapp family cows in Vermont (yes, that’s the

Sound of Music von Trapp family; after they left Europe for America in 1939, they eventually established a farm and resort in Stowe, Vermont); Humboldt Fog, a mold-ripened goat’s milk cheese with a central line of edible white ash from California; and Reblochon, a soft, raw cow’s milk cheese originating in the alpine region of Savoy in France.

Incredible cheese requires artisanal bread. The Zabar’s bread and bakery department offers everything from superb baguettes and all varieties of bagels to loaves of country sourdough, semolina, whole wheat, and raisin walnut bread, not to mention rolls, muffins, croissants, babkas, and cookies. Zabar’s own rye bread is so delicious that my Upper East Side friends take the crosstown bus to buy it. I, on the other hand, can’t come here without purchasing a half pound of cinnamon rugelach, a golden-brown crescent-shaped pastry made from cinnamon, nuts, and raisins that have been rolled into a cream cheese dough.

The bounteous prepared-food section is at the back of the store. Here, too, the choices are a gastronomic United Nations of more than twenty rotating selections, including beef bourguignon, shepherd’s pie, lasagna, potato latkes, Texas-style ribs, rotisserie chicken and duck, and poached salmon with dill sauce, as well as traditional deli meats and chicken soup with matzoh balls. It’s all prepared by three dozen cooks and assistants who toil from morning to night in two sizable kitchens in the back of the store. The menus change frequently, according to the seasons, holidays, and special events. Things begin to get particularly boisterous in this part of the store at about 6:00 p.m., when crowds of hungry customers clutching numbered tickets wait for their turn to point, grab, and go home with their dinner.

Past the prepared foods is a Zabar’s staple—the coffee station. Zabar’s is renowned for coffee that is both high quality and moderately priced, which may be why they sell between eight and ten thousand pounds a week, in the store and online. The coffee department boasts twenty-eight wooden barrels filled to the brim with shiny beans in shades of russet, tan, black, and brown that have been sourced from countries all over the world. My personal favorite is a subtly flavored hazelnut, but most customers love the basic Zabar’s roast, which is smooth and intense but not the least bit bitter. The coffee beans are blended and roasted to the store’s exacting requirements—which is to say, to the specifications of my uncle Saul, the family’s coffee aficionado. Saul was one of the initiators, if not the initiator, of the 1960s gourmet coffee movement.

All of this is just a warm-up before I proceed to the very heart of the store: the appetizing department, which includes Zabar’s legendary smoked fish. Smoked fish is so important in the lives of many of our customers that it has on occasion inspired declarations of romantic love right in front of the counter. Zabar’s most popular commodity has always been salmon, in all of its luscious varieties: cured, smoked, baked, poached, and kippered, or prepared as lox, Nova Scotia, Scotch smoked, or gravlax. Alongside the salmon, with their own fanatically devoted fan base, are Zabar’s herring, sable, and sturgeon, and, last but not least, sturgeon caviar. To this day, Saul and Tomas Rodriguez, manager of the department and assistant buyer, personally select all the fish that Zabar’s sells, and they frequently reject whatever is not up to their strict standards. I order a half pound of Nova Scotia from counterman James Bynum, who offers me a taste as he slices and as we update each other about our children and banter about current events. Just as some people have favorite bartenders or favorite barbers, some of Zabar’s customers have their special counterman, and they will wait patiently, for however long it takes, until he is available. James’s station is at the right end of the long fish counter; this spot and the one on the opposite end are reserved for the store’s most gifted slicers. Slicing fish is serious business, and it takes many months, even years, to reach a level of skill worthy of Zabar’s. An expert slicer produces gossamer slices thin enough, it is said, to read

The New York Times through. James’s hand-sliced Nova Scotia, rather than the prepackaged variety, is worth the wait. When I get back home, I will eat mine unconventionally, on a toasted sesame bagel with a layer of Zabar’s whitefish salad and a slice of tomato.

After finishing at the appetizing counter, I go upstairs to The Mezzanine because I need to replace the glass pot in my Capresso drip coffee maker. The Zabar’s housewares showroom is among the best stocked and least expensive in New York. It’s the kind of place you visit in search of a rolling pin and leave with a milk foamer, a sauté pan, a paring knife, and an avocado slicer. Quiet, enthusiastic Bernardo Muniz—the current housewares manager, born in Puerto Rico and a Zabar’s employee for thirty-seven years—is a walking kitchenwares catalog who can guide you through eighteen types of blenders and fifty different models of coffee makers, from a twenty-five- dollar plastic French press to a two-thousand- dollar behemoth that does everything but harvest the beans.

On my way out, I often drop by the Zabar’s Cafe next door, which opened in 1979. Actually, it’s more like a tiny self-service diner: long and narrow, with a communal counter, tall stools running the length of the room, and a central high-top rectangular table surrounded by more stools. When the cafe is busy, which is always, customers nudge their way around seated patrons and past a refrigerated case filled with bagels and nova, whitefish salad, and fresh-squeezed orange juice to the glass counter along the long northern wall. There they can order freshly brewed coffee, many of the baked goods found in the store, as well as warm egg sandwiches, panini, and frozen yogurt. Snagging a stool isn’t as difficult as it seems, as customers come and go quickly. If you get a perch, chances are you will be privy to two or three opinionated conversations, often among total strangers. Some regulars meet there every day to schmooze over coffee and a croissant, which means I frequently run into my relatives, neighborhood friends, or acquaintances I’ve known for years. I’ve often thought that it makes the Upper West Side seem like my grandparents’ shtetl.

To the devoted customers I encounter on these visits, Zabar’s is almost as deeply embedded in their family histories as it is in mine. Nora Ephron, who considered Zabar’s the “ultimate West Side institution,” once confessed in

The New York Times that her fantasy was to actually

be a Zabar. My mother read this and promptly invited her to brunch.

I can’t invite all of our devotees to brunch, but I can share our story. It’s not just a family story, a business story, a Jewish story, or even a New York story, but a uniquely American story. It encompasses one hundred years of family folklore, behind-the-scenes anecdotes of beloved employees and quirky customers, original Zabar-family recipes (some of which became mainstays of the store), and the evolution of the Upper West Side from bustling upper-middle-class Jewish neighborhood to down-at-the- heels and sometimes dangerous area to today’s thriving community of professionals and their families. A century after my grandparents immigrated to America, their great-grandchildren work in the business they founded and their legacy remains very much alive. This remarkable heritage includes four generations and counting of resilience, creativity, hard work, and strong family bonds. And let’s not leave out religious persecution, municipal fines, some time spent in jail, at least one blackmailer, and plenty of smoked fish.

Lori Zabar

Copyright © 2022 by Lori Zabar. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.