From the Introduction...Wherever Jews settled in the Diaspora, they created cuisines. They had to. Naturally, they were influenced by the ingredients and cooking styles of the countries in which they lived, but their kitchens were also different from the kitchens of their neighbors. Kosher dietary laws precluded their using certain foods and combinations; even more important, these laws, which progressively became more strict and all-encompassing, imposed on them a degree of culinary isolation: Jews not only cooked and ate differently, they were not allowed to sample the nonkosher food of the Gentiles. A few years ago, I watched a television interview with a Yemenite Jew who had recently arrived in Israel. When he was asked whether his food tasted different from that of his Muslim neighbors, he looked puzzled: “How would I know? I have never tried it.”

The concept of kashruth made Jewish food different. It also made it extremely significant: To a large extent Jews are defined (in their own eyes and in the eyes of the others) by what they eat and don’t eat. The centrality of cooking in Jewish culture is especially evident on Shabbat and holidays. Shabbat poses an almost impossible challenge: The day on which even the poorest must eat a proper meal is also the day on which no fire can be lit and no manual work can be done. And the result: Across the globe, unique dishes were devised for Friday-night dinners and Shabbat lunches. Holiday cooking is where Jewish cuisines are at their most exuberant. At the core of almost every holiday, there is a festive, elaborate meal—from the strictly regulated ceremonial menu served at a Passover Seder to the symbolic foods consumed at Rosh Hashanah.

Last but not least, Jewish cuisines are unique because they reflect the histories of their respective communities. Many Eastern European Ashkenazi dishes preserve archaic influences from Alsace and even Italy; the cooking of Turkish and Bulgarian Jews bears similarities to that of their ancestors during the Golden Age in Spain; the cuisines of Iraqi Jews and Indian Jews have a lot in common because of close ties between these communities.

#

This world of culinary wisdom faced dramatic changes in the twentieth century as the vast majority of those scattered in the Jewish Diaspora ceased (or nearly ceased) to exist in their original provenances. Millions of Jews from all over the world immigrated to Israel, a tiny country with an ambition to reinvent itself as a nation. The culinary baggage Jewish repatriates brought with them was at first a burden rather than a legacy. In the early days of the Zionist movement, there was an overwhelming impulse to reject the Diaspora—its customs, its language, its foods.

Later on, as waves of immigrants flooded the country in the wake of World War II, the ideological rejection was replaced by something more poignant: children ashamed of the immigrant ways of their parents—their language, their customs, their food. Be it an Ashkenazi boy embarrassed in front of his classmates because of his chopped liver sandwich or a Moroccan girl who wouldn’t let her mother serve North African sweets at her birthday party. The parents, on the other hand, clung tenaciously to their culinary legacy as a way to preserve their identities—to connect with their families, to remember their homes.

Toward the end of the millennium, as the ethos of the melting pot gave way to more inclusive approaches to everything cultural, the foods of Jewish communities became again a source of pride and inspiration, even for a younger generation, certainly for Israeli chefs. Some cuisines did better than others: Balkan and North African food traditions that suit the local climate and ingredients so well are among the most beloved in modern-day Israel. Ashkenazi food, which in the eyes of the world is synonymous with “Jewish cooking,” is less popular, but recent years have brought a new interest in it, sparked by the trendiness of Jewish Ashkenazi cooking in North America, especially in New York.

Today, more and more Israelis are aware of the importance of preserving their family cooking heritages. Self-published family cookbooks have become very common, and it is touching to see how much love and longing are invested in these modest publications. Still the big question looms: Can these cuisines, which are products of the unique circumstances of Jewish life in places like Iraq, Turkey, Yemen, Morocco, or Poland, really survive in their new home? Or to put it in simpler words: Who will cook this food in the next generation and who will eat it? Much of it is a labor-intensive, time-consuming, old-fashioned kind of cooking. Indeed, in most families it is the grandmother who still cooks the food from the old country. Her children, long since busy parents themselves, love it, but don’t have time to cook it. As for the grandchildren, they probably have tasted it only at a few family occasions, and by the time they are old enough to care and get interested, the grandmother is gone, and when they ask the mother how to make something, she often doesn’t know. “I should have asked her for the recipe but never got around to it and now it is too late.” You have no idea how often I have heard this!

Gastronomy may seem to lend itself easily to preservation, especially in our digital age. But transcribing a recipe or even videoing it is not nearly enough. The only way to really preserve a culinary culture—to keep it alive—is to cook the food and make people want to eat it. It would be naive to assume that all the wealth of Jewish cooking can be kept alive in this way. Most of it eventually will be relegated to the folkloristic fringes of the culinary scene. But in the world of Jewish food, there are so many dishes that are delicious, exciting, and doable that they can survive relocation and gain a new lease on life in the modern kitchen.

#

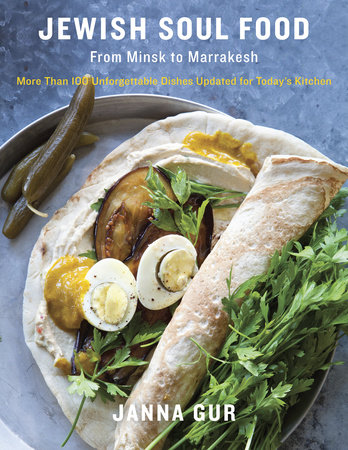

It is with these thoughts that I approached the project that eventually became this book. The Jewish bookshelf is brimming with excellent works. Some of them are encyclopedic in their scope; others, dedicated to the cooking of a specific community, offer a captivating blend of recipes, folklore, and history. But this depth and scope can sometimes be overwhelming, especially to someone new in the field. I felt that what was missing was something more focused, edited, and therefore approachable; I decided to confine myself to about one hundred dishes from as many Jewish communities as possible—a kind of greatest hits from our Jewish grandmothers.

In selecting the dishes, I tried to crack the code of a winning dish—what is it that makes us adopt and adapt a certain recipe and abandon another? Surely, there’s the relative ease of preparation, and the availability of ingredients, but there’s something else—the “soul” of a dish, that elusive quality that makes us relish it and want to make it ours. To discover that soul was my goal, but I cannot really claim that it was just I who curated this selection.

Israel today is a living laboratory of Jewish food, as our cooks, both professional and amateur, are exposed to a multitude of cuisines and dishes. Through a process of natural selection, some of them have been discovered and adopted by the whole society because of their deliciousness and practicality. In this respect, the real editors of this collection are anonymous Israelis who prepare these dishes in their kitchens or order them in restaurants, and in this way are keeping them alive.

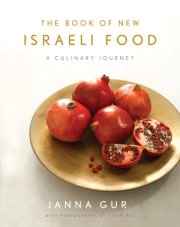

I was also very lucky: During the twenty-odd years of editing an Israeli food magazine, I learned from many great cooks around me and was able to compare different versions of the same dish. Many recipes in this book are indeed credited to specific cooks—professional and amateur—while others are the sum total of tips and techniques I picked up along the way.

Most recipes are authentic (often with little tweaks that make life easier), but here and there I was tempted to offer a creative take on a traditional dish: like Erez Komarovsky’s Gondalach—a charming fusion of Ashenazi kneidlach and Persian gondi dumplings; or Omer Miller’s Exiles Cholent, which cleverly blends ingredients and techniques from several Shabbat casseroles with delicious results.

It was important for me to show that these dishes feel perfectly at home in a modern kitchen (they certainly do in mine): The salads and snacks featured in the first chapter are great for parties and cookouts; Meatless Mains offers healthful and nutritious options for both weekday and special-occasion meals. The Shabbat chapter might lead you to rethink your weekend menu and invite friends for “Sabich breakfast” or serve them a visually stunning and easy-to-make Hamin Macaroni.

As these recipes come from so many different cuisines, some of the ingredients might be a little hard to come by. Wherever possible, more readily available substitutes are suggested, but I do urge you to try to get the real stuff at least once—the difference can be dramatic.

To use a culinary metaphor, I would like to regard this selection as an appetizer—a sampler that will encourage you to explore more dishes from various Jewish cuisines. If you enjoy Lakhoukh panfried bread, you might be tempted to look further afield and discover other distinctive breads from the Yemenite kitchen; while T’bit—an ingenious Iraqi Shabbat casserole—could be a wonderful introduction to one of the most ancient and unique Jewish cuisines. I can also envision a different scenario—your encountering a dish that you remember from your childhood and deciding, for the first time in your life, to make it in your own kitchen.

Either way, every dish you cook from this book (or other Jewish cookbooks for that matter) is meaningful in a way that goes beyond its taste and your personal enjoyment. By cooking it and serving it to those you love, you help to keep it alive and pass it on to the next generation.

Copyright © 2014 by Janna Gur. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.