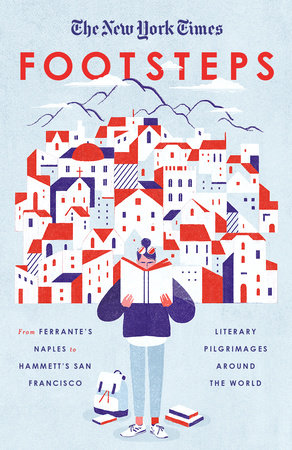

From the Introduction, by Monica DrakeBack when travel was just my passion and not yet my profession, I went to the French Riviera for the party scene and in- stead found myself dazzled by the otherworldly light of day. I was marveling at how it made every waking moment dream- like when I noticed a small plaque on a building indicating that Henri Matisse had lived inside. Whatever I’d read about Matisse and Nice before that moment hadn’t mattered: It was then that I understood how the city had challenged him to make art as sublime as the setting.

All of us have experienced a moment in our travels when we stray onto turf that an artist, including those who paint pictures with words, once trod. It surprises us, this statue in the middle of a park, a street named for a luminary, or the small museum that at one point was her home. But it shouldn’t be unexpected.

All the world is a reliquary, filled with fields, forests, and city plazas that lead visionaries among us to create work that endures the ages. We travelers are but devotees who touch these monuments and in place of prayers meditate on how someone else came to be who they are and create what they did. We inevitably look about and wonder. Did the sweep of this hill and the mist of the morning somehow ignite a spark? Was this place more incidental than inspirational? Examining these questions has been the defining task of Footsteps since 1981, when

The Times ran it as a short-lived series. It appeared sporadically in the intervening years until it emerged as a full-fledged feature.

Regardless of provenance, the conceit in these pages is nearly as old as

The Times itself. An article from 1860 chronicles a visit to Stratford-on-Avon to see the birthplace and tomb of the “world’s master-genius,” William Shakespeare. That report, a faithful recounting of a voyage in the footsteps of someone universally revered, assumed the best of the Bard: “Calm, quiet and beautiful were all the surroundings, and I thought it was not strange that one whose early childhood was passed amid such scenes as this should have partaken of their beauty, and been gentle, kind and loving.” In aspiring to capture the interplay of a writer’s real identity, work, and setting, this was an early version of what would become Footsteps.

As the breadth of the stories in this collection indicates, our approach varies as much as the literary giants that they profile. “Mark Twain’s Hawaii,” for example, examines the four-month stretch in which the writer sent letters from the island, rather than tracing any of his fictional works. Yet it suffuses the place with the spirit of Twain. “Orhan Parmuk’s Istanbul” is on the other end of the spectrum, using the Nobel laureate as a tour guide who leads us through the city that he has called home for nearly six decades.

What unifies them is a single guiding principle: Each should leave a reader with a new perspective on an artist and the place that has somehow been a muse. Often an unusual pairing is enough to supply the novelty—as with Rimbaud in Ethiopia, a lesser-examined point in the poet’s life. But occasionally—as with Dashiell Hammett and San Francisco—the setting and star go hand in hand until the story of the city’s transformation is taken into account. There is little hard-boiled left in a city awash in venture capital, it turns out. As Footsteps evolves,

The Times has been venturing farther afield to choose the settings. Inspiration comes from America and Europe and also from Chile (Borges), Martinique (Cesaire) and Vietnam (Duras). We’ve also added contemporary personalities such as Jamaica Kincaid and Elena Ferrante to those whose trails we trace.

At the same time, we seek contributors who are able to view the place and the person they are profiling with equal fervor. The best of our Footsteps capture their passion for specific authors and places in time.

These escapes immerse travelers in a setting by providing a purpose while on the road. A fixed mission forces us to be present rather than meander about, refreshing our social feeds and lamenting the cost of international roaming. Studying the world this way pushes away workaday life that much more efficiently. These accounts can make us travelers instead of tourists.

And that they do, even if you do not take a trip. “That was a pleasant journey into the real Wonderland,” a reader wrote in response to the description of Lewis Carroll’s Oxford. It isn’t rare for readers to send e-mails and comments and letters that refer to a Footsteps essay as if it had been a vacation.

True literature itself is a flight of fancy, and appreciators of it are all too familiar with the discombobulating feeling of finishing a novel and being slightly surprised to be at home in a recliner rather than hundreds of miles—and hundreds of years—away. Above all, Footsteps essays are for the avid readers who can travel by simply turning a page. Turn these, and they’ll take you around the world.

Copyright © 2017 by New York Times. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.