INTRODUCTION Paris: Pot on the Fire

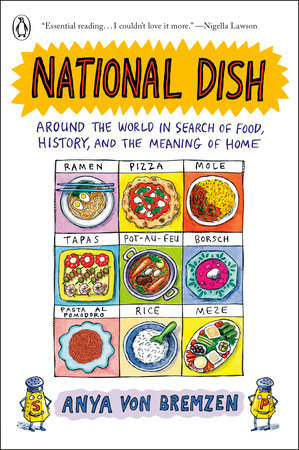

On a gray fall morning in the days sometime before the pandemic, my partner Barry and I arrived in Paris, where I planned to make a pot-au-feu recipe from a nineteenth-century French cookbook. It was for a book project of my own, one that had begun to bubble and form in my mind, about national food cultures told through their symbolic dishes and meals, which I would cook, eat, and investigate in different parts of the world.

Dumping our luggage in our apartment swap in the multicultural 13th arrondissement, we immediately rushed across the wide Avenue d'Italie-to begin sabotaging French national food culture by ingesting a frenzy of calories.

Non-Gallic calories.

At a petite dive called Mekong, a stupendous curried chicken banh mi was prepared with something like love by a tired Vietnamese woman who sighed that Saigon was

très belle, mais Paris? Eh bien, un peau triste . . . At a halal Maghrebi boucherie there was mahjouba, a flaky Algerian crepe aromatic with a filling of stewed tomatoes and peppers. And a mustached butcher being tormented by a middle-aged Parisienne, prim and imperious. After she departed with her single veal escalope, he exhaled with a whistle and made a "crazy" sign with his finger.

Which pretty much summed up how I'd always felt about Paris.

Ever since my first visit back in the 1970s, as a sullen teenage refugee from the USSR newly settled in Philadelphia, my relationship with the City of Light had always been anxious and fraught. Other people might swoon over the bistros, rhapsodize about first encounters with platters of oysters and crocks of terrine. Me, I saw nothing but despotic prix fixe menus, withering classism, and Haussmann's relentless beige facades-assembly-line Stalinism epauletted with window geraniums.

But

right now, onward, for pink mochi balls at a Korean épicerie on the main Asian artery, Avenue de Choisy, after which I frantically stuffed our shopping bag with frozen Cambodian dumplings and three huge Chinese moon cakes at the giant Asian supermarket, Tang Frères. Just nearby, at a fluorescent-lit Taiwanese bubble tea parlor, was where I discovered the Vietnamese summer roll-sushi mashup. Behold the sushiburrito.

It was the happiest Paris arrival I'd ever had. The 13th arrondissement comforted me right back to where I'd just left, my buoyant polyglot New York neighborhood of Jackson Heights, Queens. The postcolonial profusion of lemongrass, fish sauce, and harissa helped soften my Francophobic unease.

Sending Barry off to settle into our apartment swap-whose tiny cramped kitchen, by some astounding kismet, featured a large poster of Frederick Wiseman’s documentary

In Jackson Heights-I carried my purchases to our petite neighborhood park. South Asian and North African kids were kicking a soccer ball by the hibiscus bushes. On a bench, a Koranic old man with a wispy beard and a skullcap put his hand to his heart to greet me: “As-salaam alaikum!”

With this blessing and a test bite of moon cake (funky salted egg filling), I pondered that which had brought me to Paris-a place unbeloved by me, but historically crucial to the concept of a national food culture. My journey could hardly start anywhere else.

National cuisines, one food studies scholar observes, suffer from “problematic obviousness.” The same could be said for the very idea of “national.” Most of us take a view of nations as organic communities that have shared blood ties, race, language, culture, and diet since time immemorial. Among social scientists, however, this “primordialism” doesn’t hold water. Scholars from the influential mid-1980s “modernist” school (Ernest Gellner, Eric Hobsbawm, Benedict Anderson) have persuasively argued that nations and nationalism are historically recent phenomena, dating roughly to the late Enlightenment-and to the French Revolution in particular, which supplied the model for our contemporary concept of the nation, as France’s absolutist monarchy of divergent peoples and customs and dialects was transformed into a sovereign entity of common laws, a unified language, and a written constitution, ruled in the name of equal citizens under that grand idealist banner: Liberté, égalité, fraternité!

Inspired by the French example, the long nineteenth century would see the rise of ethnonational self-determination from colonial empires, until the first and second world wars released flood tides of new nation-states from the ruins-some of their current borders, of course, blatant carve-ups by European colonial powers.

The final wave of nations arrived in the early 1990s with the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the USSR. It was in the latter where I was born in the sixties, to be raised on the imperialist scarlet-blazed myth of the fraternity of Soviet socialist republics-as diverse as Nordic Estonia and desert Turkmenistan-all wisely governed by Moscow, my hometown. The food we relished was the disparate cuisine of an empire: Uzbek pilaf, spicy Georgian chicken in walnut sauce, briny Armenian dolmas; they relieved the quotidian blandness of Soviet-issue sosiski (franks) and mayonnaise-laden salads.

Then in 1974 my mother and I became stateless refugees, emigrants to the US.

I still remember my ESL teacher lecturing grandly in a loud, nasal Philadelphia accent about how proud we students should feel being part of a glorious melting-pot nation. And me trying to imagine myself somehow as a slice of weird Day-Glo-orange Velveeta melting away in the cauldron of gloppy chili of our school lunches. Instinctively wary of the great American assimilationist model, I didn't melt in very well. My overbearing patriotic Soviet education made me cynical about states and their identities.

Though now I sometimes wonder how it would feel to belong to a small, close-knit nation-Iceland?-I feel most at home in my Jackson Heights barrio of 168 languages, where I can have Colombian arepas for breakfast and Tibetan momos for lunch, and nobody cares about my identity. I'm a Jewish-Russian American national, born in a despotic imperium long deleted from maps. I speak with a heavy accent in several languages, lead a professionally nomadic existence as a food and travel writer, and own an apartment in Istanbul, former seat of the multiethnic Ottoman empire. At table my mom, Barry, and I are passionate ecumenical culturalists. We make gefilte fish for Passover, Persian pilaf for Nowruz, and a ham for Russian Orthodox Easter. The Polish philosopher Zygmunt Bauman has a great phrase for this very common postmodern-globalized-condition, of not committing to a single identity or place or community:

"Liquid modernity," he calls it. A life where "there are no permanent bonds."

So why then would someone like me set out to explore

national food cultures?

Because with the rise and domination of globalization, nations and nationalism somehow seem both more obsolete and more vital and relevant than ever. There's hardly a better prism through which to see this than food. From Kampala to Kathmandu we confront the same omnipresent fast-food burger, while from Tbilisi to Tel Aviv the same "global Brooklyn" community of woolly hipsters protests such corporate/culinary imperialism with craft beer and Instagrammable sourdough loaves. In a way, both the craft brews and the burgers are different political flavors of transnational food flows. Such full-flood globalization, you'd think, would have wiped away local and national cravings. But no: the global and local nourish each other. Never have we been more cosmopolitan about what we eat-and yet never more essentialist, locavore, and particularist. As the world becomes ever more

liquid, we argue about culinary appropriation and cultural ownership, seeking anchor and comfort in the mantras of authenticity, terroir, heritage. We have a compulsion to tie food to place, to forage for the genius loci on our pilgrimages to the birthplace of ramen, the cradle of pizza, the bouillabaisse bastion. Which is what I've been doing myself professionally for the last several decades.

What's more, as a national symbol, food carries the emotional charge of a flag and an anthem, those "invented traditions" crucial to building and sustaining a nation, to claiming deep historical roots. While in fact, often, they are both manufactured and recent.

And so here I sat on a bench in Paris, unwrapping my hyperglobalized sushiburrito while contemplating a super-essentialist quote from the great scholar Pascal Ory. France, wrote Ory, “is not a country with an ordinary relation to food. In the national vulgate food is one of the distinctive ingredients, if not the distinctive ingredient, of French identity.”

Italians, Koreans, even Abkhazians would certainly wax indignant that their relation to food is every bit as special. But if our identities, at their most primal, involve how we talk about ourselves around a dinner table, it was France-and Paris specifically-that created the first explicitly national discourse about food, esteeming its cuisine as an exportable, uniquely French cultural product along with terms such as "chef" and "gastronomy." It was France that in the mid-seventeenth century laid the foundation as well for a truly modern cuisine, one that emerged from a jumble of medieval spices to invent and record sauces and techniques the world still utilizes today. To create "restaurants" as we know them, and turn "terroir" into a powerful national marketing tool.

Of course (to my not-so-secret glee, I admit) this Gallic culinary exceptionalism had taken a terrific beating over the past couple decades. So where was it now? And where, and how, did the idea of France as a "culinary country" come to be born?

The pot-au-feu that was to occupy me in Paris, my symbolic French national meal, came from a book by a deeply influential nineteenth-century chef whose fantastical story befits an epic novel. Abandoned on a Parisian street by his destitute father during Robespierre’s terror, Marie-Antoine Carême would have been invented-by Balzac? Dumas père? both were gourmandizing fans-if he didn’t already exist. Self-made and charismatic, he rose to become the world’s first international celebrity toque (in fact he invented the headgear). Not only was Carême the grand maestro of

la grande cuisine’s architectural spun-sugar spectaculars, he also codified the four mother sauces from which flowed the infinite “petites sauces,” sauce being so essential to the French self-definition. And cheffing for royalty and the G7 set of his day, he spread the supremacy of Gallic cuisine across the globe. Or to put a modern spin on it, Carême conducted gastrodiplomacy (our au courant term for the political soft power of food) on behalf of Brand France.

Even more influential was Carême's written chauvinism. "Oh France, my beautiful homeland," he apostrophized in his 1833 seminal opus,

L'Art de la Cuisine Française au Dix-Neuvième Siècle, "you alone unite in your breast the delights of gastronomy."

How then

are national cuisines and food cultures created? The answer, as I’d come to learn, is rarely straightforward, but a seminal cookbook is always a good place to begin. And as the influential scholar of French history Priscilla Ferguson observed, it was Carême’s books that unified La France around its cuisine and food language, at a time when French printed texts had begun making the ancien régime’s aristocratic gastronomy accessible to an eager, more inclusive bourgeois public. “Carême’s French cuisine,” Ferguson writes, “became a key building block in the vast project of constructing a nation out of a divided country.”

As the Chef of Kings addressed his public: "My book is not written for the great houses. Instead . . . I want that in our beautiful France, every citizen can eat succulent meals."

And the succulence that kicks off his magnum opus is the pot-au-feu, "pot on the fire." Broth, beef, and vegetables, soup and main course all in one cauldron, it's a symbolic bowlful of égalité-fraternité that Carême anointed

un plat proprement national, a truly national dish. Pot-au-feu carries a monumental weight in French culture. Voltaire affiliates it with good manners; Balzac and even Michel Houellebecq, that scabrous provocateur, lovingly invoke its bourgeois comforts; scholars rate it a "mythical center of family gatherings." Myself, I was particularly intrigued by its liquid component, the stock or bouillon/broth-the aromatic foundation of the entire French sauce and potage edifice.

"Stock," proclaimed Carême's successor, Auguste Escoffier, dictator of belle epoque haughty splendor, "is everything in cooking, at least in French cooking."

Stock was homey yet at the same time existentially Cartesian:

I make bouillon, therefore I cook à la française. ”Carême . . . pot-au-feu . . . such important subjects.” Bénédict Beaugé, the great French gastronomic historian, saluted my project. “And these days, alas, so often ignored.”

In his seventies, his nobly benevolent face ghostly pale under thinning white hair, Bénédict radiated a deep, humble humanity-the opposite of a blustery French intellectual. His book-lined apartment lay fairly near the Eiffel Tower, in Paris's west. Walking up his bland street, Rue de Lourmel, I noted a Middle Eastern self-service, a Japanese spot, and a wannabe hipster bar called Plan B.

"Ah, the new

global Paris," I remarked, to open our conversation.

"And a chaos, culinarily speaking," Bénédict said. "A confusion-reflecting a larger one about our identity-lasting now for almost two decades . . . Though a constructive chaos, perhaps?"

He wondered, however, as I'd been wondering, about the "overarching idea of Frenchness, of a great civilization at table." In Paris nowadays, he said, only Japanese chefs seemed fascinated with Frenchness, while Tunisian bakers were winning the Best Baguette competitions.

"Yes, immigrant cuisines are changing Paris for the good," he affirmed. "But the problem? In France, we don't have your American clarity about being a melting-pot nation."

Indeed. Asking journalist friends about the ethnic composition of Paris, I'd been sternly reminded that French law prohibits official data on ethnicity, race, or religion-effectively rendering immigrant communities like the ones in our treizième mute and invisible. All in the name of republican ideals of color-blind universalism.

"Ah, but pot-au-feu!" Bénédict nodded approvingly. "That wonderful, curious thing, a dish entirely archetypal-meat in broth!-and yet totally national!"

As for Carême? He smiled tenderly as if talking about a beloved old uncle. "An artiste, our kitchen's first intellectual, a Cartesian spirit who gave French cuisine its logical foundation, a grammar.

However . . ." A finger was raised. "The rationalization and ensuing

nationalization of French cuisine-it didn't exactly begin with Carême!"

"Ah, you mean La Varenne," I replied.

Copyright © 2023 by Anya von Bremzen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.