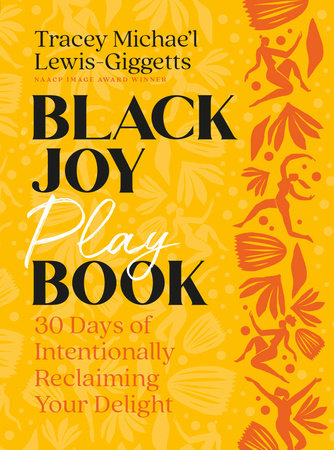

Introduction

Trusting the SilenceIn 2019, the only place where I felt well was my bed. If I stood for any length of time, I became dizzy. My limbs were a weight that made me feel as though I were walking through mud. Every muscle in my body would periodically tighten like a vice grip squeezing the life out of me. At least that’s the way it felt. And the worst part of it? There wasn’t a single doctor who could explain what was happening to me.

In hindsight, I understand that my body had simply had enough. It was done with all my running around. All the wear and tear. All the hustling and grinding I thought I needed to do to feel worthy and valuable and loved. It had collapsed under the weight of grief I’d yet to reckon with. So my body had decided to shut down, seemingly in protest.

I was left with nothing else but my bed and the silence.

Oh, the silence. That was probably the hardest thing to bear. I was used to the noise. I was comfortable with all the voices in my head pushing me to do more, more, more. The voices of all those parts of me who had never felt safe unless I was moving, moving, moving. When I was forced to be still, I was also forced to lay my resistance aside. I was forced to lay down the thing I’d defined myself by as a Black woman: my ability to be strong, to fight. And in my surrender, I was left with the quiet— and a quest.

Deep down, I knew my future work as a writer and educator would depend on my embracing this silence. Kevin Quashie wrote in

The Sovereignty of Quiet, “The black artist . . . , if she or he is to produce meaningful work, has to construct a consciousness that exists beyond the expectation of resistance. . . . Quiet, instead, is a metaphor for the full range of one’s inner life—one’s desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears. . . . Quiet is inevitable, essential. It is a simple, beautiful part of what it means to be alive.” To truly see my dreams come true, to have the vision of my life come to fruition, this was a truth I had to embrace. I needed to trust the silence to do its work.

God always had a plan for me. I just needed to be still long enough to hear it.

Then, of course, there was that nagging question asked of me by a very knowing therapist. “What does joy feel like in your body, Tracey?”

More silence.

I did not know the answer. I wasn’t even sure I knew how to find it out. But the silence was compelling. It created a safe environment for me to unpack all my beliefs about myself, God, and people around me and to begin my own personal joy journey.

So, yes, reckoning with, accessing, and amplifying my joy began in the most unlikely of places: in the silence. I had to get still in ways I never had before so joy felt safe enough to make itself known. It had been crowded out for a long time. Other emotions and states of being had taken up significant space. Rage and grief and exhaustion were so big in my body, mind, and spirit that joy and love and peace could occupy only a tiny, minuscule corner of my heart. But the silence drew them out. As Renita Weems said in

Listening for God, “I accepted the silence,”2 and, in doing so, gave myself permission to hold all the joy I could stand.

That is what I hope the pages of this journal will offer you. A place for you to name and reclaim your joy. A canvas where you can paint the complexities of what it means to be a Black person in this world, with the understanding that we must always leave a little white space, a little margin for ourselves, especially when nothing but productivity and labor is deemed our lot. It’s why I’ve chosen to include quotes from a variety of historical, sociological, and literary figures, some of whom may or may not be overtly Christian voices. I recognize that the truths found in all our lived experiences play an important part in how we understand, engage, and receive joy in our lives, no matter the faith tradition we claim. I pray that as you make your way through each entry, you give yourself room to move and play and restore what life has tried to steal from you. Even what you might have unknowingly given away.

That said, as a person of faith, I know and believe that above and beyond defining joy as a physiological response to pleasure, and Black joy as that same response housed within the specific historical and sociopolitical context that comes with being in this skin, ultimately joy is a person. Jesus embodies joy for us in the same way he embodies the more preached-about attributes of love and peace. And that joy has been a resurrecting power in my life. It is one I hope you see in your own.

As you journey through this devotional, you will notice there are more days spent exploring through guided prompts of what it means to know joy in our bodies. I’ve designed it that way. Our bodies are the starting points. When we can locate and recognize what joy feels like in our bodies—how much or how little space joy takes up and how our central nervous systems play huge roles in how we experience joy—only then can we move forward with creating more joy in our environments and relationships. In addition to those guided prompts, you will also find freewriting space in the Play by Play sections, where you can write down any feelings that come up for you each day and work out your joy plan in real time.

I invite you to approach this guided journal with intention, and as you take this journey with me for the next thirty days, I hope part of that intention will be to remember that joy is your birthright. We have an ancestral mandate not just to hold the pain and trauma of our experiences as Black people but also to hold the joy and love and peace that is ours too. In these pages, you are safe to explore joy and play and pleasure in a way that honors your lived experiences and expands them.

Welcome to your Black joy playbook! May your joy overflow in the most glorious ways.

—TMLG

Copyright © 2024 by Tracey Michae'l Lewis-Giggetts. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.