OneThey had come to the spot in the freshness of June, chased from the village by its people, threading deer path through the forest, the valleys, the fern groves, and the quaking bogs.

Fast they ran! Steam rose from the fens and meadows. Bramble tore at their clothing, shredding it to rags that hung about their shoulders. They crashed through thickets, hid in tree hollows and bear caves, rattling sticks before they slipped inside. They fled as if it were a child’s game, as if they had made off with plunder. My plunder, he whispered, as he touched her lips.

They laughed with the glee of it. They could not be found! Solemn men marched past them with harquebuses cocked in their elbows, peered into the undergrowth, stuffed greasy pinches of tobacco into their pipes. The world had closed over them. Gone was England, gone the Colony. They were Nature’s wards now, he told her, they had crossed into a Realm. Lying beneath him in the litter, in the low hollow of an oak, she arced her head to watch the belted boots and leather scabbards swinging across the wormy ceiling of the world. So close! she thought, biting his hand to stifle her joy. Entwined, they watched the stalking dogs and met their eyes, saw recognition cross their dog-faces, the conspiring shiver of their tails as they continued on.

They ran. In open fields, they hid within the shadows of the bird flocks, in the rivers below the silvery ceiling of the fish. Their soles peeled from their shoes. They bound them with their rags, with bark, then lost them in the sucking fens. Barefoot they ran through the forest, and in the sheltered, sappy bowers, when they thought they were alone, he drew splinters from her feet. They were young and they could run for hours, and June had blessed them with her berries, her untended farmer’s carts. They paused to eat, to sleep, to steal, to roll in the rustling meadows of goldenrod. In hidden ponds, he lifted her dripping from the water, set her on the mossy stone, and kissed the river streaming from her tresses and her legs.

Did he know where he was going, she asked him, pulling him to her, tasting his mouth, and always he answered, Away! North they went, to the north woods and then toward sun-fall, trespassing like fire, but the mountains bent their course and the bogs detained them, and after a week they could have been anywhere. Did it matter? Rivers carried them off and settled them on distant, sun-warmed banks. The bramble parted, closed behind them. In the cataracts, she felt the spring melt pounding her shoulders, watched him picking his way over the streambed, hunting creekfish with his hands. And he was waiting for her, winged in a damp blanket which he wrapped around her, lowering her to the earth.

They had met in, of all places, church. She had known of him, been warned of him, heard that he stirred up trouble back in England, had joined the ships only to escape. Fled Plymouth, fled New Haven, to settle in a hut on Springfield’s edge. They said he was ungodly, consorted with heathens, disappeared into the woods to join in savage ritual. Twice she’d seen him watching her; once she met him on the road. This was all, but this was all she needed. She felt that she had sprung from him. He watched her through the sermon, and she felt her neck grow warm beneath his gaze. Outside, he asked her to meet him in the meadow, and in the meadow, he asked her to meet him by the river’s bank. She was to be married to John Stone, a minister of twice her age, whose first wife had died with child. Died beaten with child, her sister told her, died from her wounds. On the shore, beneath the watch of egrets, her lover wrapped his fingers into hers, made promises, rolled his grass sprig with his tongue. She’d been there seven years. They left that night, a comet lighting the heavens in the direction of their flight.

From a midwife’s garden: three potatoes. Hardtack from the pocket of a sleeping shepherd. A chicken from a settler’s homestead, a laying chicken, which he carried tucked beneath his arm. My sprite! he called his lover in the shelter of the darkness, and she looked back into his eyes. He was mad, she thought, naked but for his scraps of clothing, his axe, his clucking hen. And how he talked! Of Flora, the dominion of the toad and muck-clam, the starscapes of the fireflies, the reign of wolf and bear and bloom of mold. And around them, in the forest, everywhere: the spirits of each bird and insect, each fir, each fish.

She laughed—for how could there be space? There’d be more fish than river. More bird than sky. A thousand angels on a blade of grass.

Shh, he said, his lips on hers, lest she offend them: the raccoon, the worm, the toad, the will-o’-

the-wisp.

They ran. They married in the bower, said oaths within the oaken hollow. On the trees grew mushrooms large as saddles. Grey birds, red snakes, and orange newts their witnesses. The huckleberries tossed their flowers. The smell of hay rose from the fern they crushed. And the sound, the whir, the roar of the world.

They ran. The last farms far behind them; now only forest. They followed Indian paths through groves hollowed by fire, with high green vaults of celestial scale. On the hottest days, they climbed the rivers, chicken on his shoulder, her hand in his. Mica dusted her heels like silver. Damselflies upon her neck. Flying squirrels in the trees above them, and in the silty sand the great tracks of cats. Sometimes, he stopped and showed her signs of human passage. Friends, he said, and said that he could speak the language of the people this side of the mountains. But where were they? she wondered. And she stared into the green that surrounded them, for fear was in her, and loneliness, and she didn’t know which one was worse.

And then, one morning, they woke in the pine duff, and he declared they were no longer hunted. He knew by the silence, the air, the clear warp of summer wind. The country had received them. In the Colony, two black lines were drawn through two names in the register. The children warned of thrashings if they spoke of them again.

They reached the valley on the seventh day. Above them, a mountain. Deer track led through a meadow that rose and narrowed northly, crossed through the dark remnants of a recent fire. A thin trail followed a tumbling brook to a pond lined with rushes. Across the slope: a clearing, beaver stumps and pale-green seedlings rising from the rich black ash.

Here, he said.

Songbirds flitted through the burn. They stripped their last rags, swam, and slept. It was all so clear, so pure. From his little bag, he withdrew a pouch containing seeds of squash and corn and fragments of potato. Began to pace across the hillside, the chicken following at his feet. At the brook, he found a wide, flat stone, pried it from the earth, and carried it back into the clearing, where he laid it gently in the soil. Here.

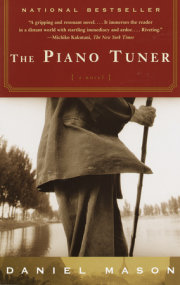

Copyright © 2023 by Daniel Mason. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.