Introduction John J. Lee, Chee Wang Ng & Mae NgaiThis is the story of a man who endeavored to change the world, one photograph at a time. Who dared to create a record of an upheaval—of thoughts and beliefs that held a people down, of an ignorant nation that prevented the growth of ideas new and better. The truth and a bit of justice. This is the story of our brother and friend, whom the world came to know as Corky Lee.

With each photograph he took, Corky aimed to break the stereotype of Asian Americans as docile, passive, and above all, foreign to the United States. He insisted that Asian Americans are Americans, that they were, and are, part of this country, of its history and the ongoing project of its making. As he wrote after 9/11, “Do not let anyone tell you to go back to the country of your ancestors. You belong here. Immigrants built America. It was created for you and me.”

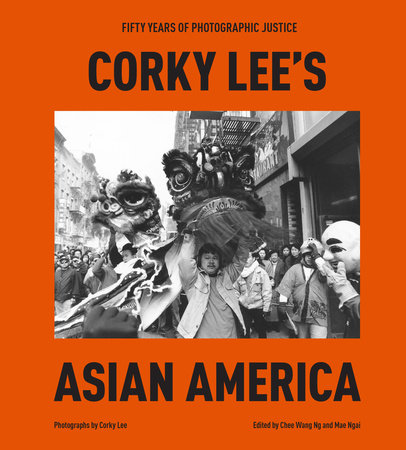

Corky Lee documented Asian American–Pacific Islander communities for fifty continuous years, from 1970 to 2020, until we lost him during the pandemic in January 2021, at the age of seventy-three. This book is a retrospective of his life’s work, a selection of the best photographs from his vast collection, starting in New York’s Chinatown and extending to diverse Asian American communities across the country.

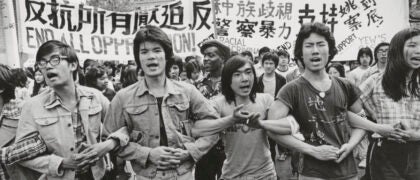

If Corky aimed to break stereotypes one photograph at a time, his photographs, taken together, show the amazing growth and diversity of Asian peoples in America in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. They offer a view—a long view—of the rise and development of the Asian American movement for civil rights and social justice.

Corky Lee was a social photographer—he had little interest in haute art or commercial photography. He sometimes described himself, and was described by others, as a photojournalist. But he was always aware of the limits on photojournalism imposed by editorial gatekeepers and remained true to his first calling as a documentarian of the Asian American community and movement. His intention was to use photography to educate and organize. He avidly photographed protest demonstrations and cultural celebrations as well as children at play, families in their homes, and people at work, be they restaurant kitchen workers or, more atypically, cops and firefighters, pizza and bagel makers, and women taxi drivers, boxers, and pool sharks.

Following trends in politics and culture, Corky used the pan-ethnic identifier “Asian American– Pacific Islander” (AAPI) to refer to his subject matter. His photographs track the growth of the AAPI movement for equality and social justice, spanning a range of issues, from demonstrations against police and racist violence to protests against racial stereotyping in film and theater productions. In the early 1990s, when tension developed between Korean grocers and their Black customers in Brooklyn, Corky documented it. When racism erupted against Sikh Americans in the aftermath of 9/11, Corky was there with his camera. He photographed the rise of the Basement Workshop, a collective of Asian American artists and activists, in the 1970s, and the National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance in the 2000s. He recorded solidarity between Asian Americans and other communities of color, like the Black Lives Matter movement. As cultural heritage events proliferated in number and diversity, reflecting the new Asian immigrations in the 1980s and 1990s—parades for India Day, Sikh Day, Korea Day, and the like—Corky was there to show us what they looked like.

While Corky photographed diverse AAPI cultures, New York City’s Chinatown remained at the center of his social and photographic world. His long association with this community generated a high level of photographic achievement. Corky knew and loved Chinatown deeply, calling it “a part of my soul.” His portrayal of Chinatown life was at once social and personal, documentary and artistic. He captured ordinary people in their social environment and objects in stilllife compositions, like a tenement fire escape. Some of his photographs of community events, like dragon boat races, express joyous energy, but others are intimate, like an opera singer sitting on a park bench, adjusting her hairpiece. Some show provocative juxtapositions, like American Legion members and beauty pageant contestants lined up for the Chinatown Fourth of July parade. His late photos, taken of a lonely and shuttered Chinatown in 2020 during the first year of the pandemic, reveal that over decades of experience in the community, he had honed a very special kind of eye.

Corky considered his greatest triumph to be a 2014 photograph in which 250 Asian Americans, including direct descendants of Chinese railroad workers, reenact the completion of the transcontinental railroad. He had long sought to correct the famous photograph taken of the railroad’s completion in 1869, which had no Chinese in it, even though upward of twenty thousand Chinese workers had built the western part of the line, including the arduous tunneling of the Sierra Nevada. Corky called his reenactment a work of “photographic justice.”

This book is the result of a collaboration between John J. Lee, Corky Lee’s sole surviving brother and executor of his estate; Mae Ngai, a professor of history and Asian American studies at Columbia University; and Chee Wang Ng, an artist-photographer and Corky’s longtime colleague.

Mae first met Corky in the early 1970s, when she—like scores of other young people—moved to New York’s Chinatown to join the emerging Asian American movement. She joined the radical group I Wor Kuen, then got a job as a nurse’s aide at Gouverneur Hospital, where she became active in the labor movement. She later moved away from Chinatown and eventually became a professor, specializing in immigration and Asian American history. Her last contact with Corky was in the late fall of 2019, when she invited him to mount a photo exhibition at the ethnic studies center at Columbia University. Corky took measurements at the gallery and mused about a potential theme. A few months later, though, the pandemic shut everything down, and the exhibition never materialized.

Chee Wang Ng’s personal and professional friendship with Corky was thirty years long. Born in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, he came to the United States in the 1980s and earned a bachelor of fine arts in architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design. An artist-photographer, he has been active in the Chinatown–Asian American art and photography scene since the 1990s. In 2002, when Corky was invited to do a solo show at the Asian American Arts Centre in Chinatown, he instead chose to exhibit the work of eight other Asian American photographers, knowing they had limited opportunities in New York at the time, and Chee Wang was one of them. Over the years, Chee Wang worked with Corky as a graphic designer, participated in group shows with him, and helped him curate and prepare for many of his exhibitions.

In the fall of 2021, John reached out to Mae and Chee Wang to help him fulfill his late brother’s dream of publishing a book of his photographs. Our job as co-editors, as we saw it, was to select the best of Corky’s work and to present it in a historical and social context. Still, it was a daunting challenge. Corky once estimated that he took an average of two hundred photographs a week. Over the course of his fifty-year career, that adds up to a half-million images. How would we select the photographs for the book?

We started with the photographs that Corky himself had selected in 2011 for a book that he intended to self-publish. He chose one hundred photos, gave the book a title, Not on the Menu, and created a mock-up with Chee Wang. A friend donated the funds for the purchase of paper for the publication. But as with many things in life, the book was put aside in the everyday crush of work and other matters.

To that selection, we added photographs that Corky took in the last decade of his life. We considered the most important to be those that he chose for exhibitions or loaned out for films and other creative projects. Taken together, they represent the ones Corky himself considered to be his best work.

Finally, we have added some never-beforeseen gems from Corky’s archive. We found some of them in old metal boxes of slides and on newer digital storage disks. Others were sent to us by Corky’s friends and acquaintances from their personal collections.

Corky Lee’s fifty-year quest for “photographic justice” unfolds in these pages. The initial essay by Mae Ngai, “An ABC from NYC,” situates his life and career in the context of American history and the history of photography. Then the book presents Corky Lee’s photographs, organized in three chronological chapters. The sequence tracks AAPI social movements’ struggle for recognition and rights and simultaneously Corky’s artistic development as a social photographer and activist. Each chapter begins with an introduction that situates the time and place of the photographs within it. Essays by Asian American writers, artists, activists, and friends of Corky’s—including filmmaker Renee Tajima-Peña, writer Helen Zia, historians Gordon Chang and Vivek Bald, playwright David Henry Hwang, and photographer Alan Chin—give greater context to each chapter’s major themes and reflect on their relationship to Corky.

Copyright © 2024 by Corky Lee; Edited by Chee Wang Ng and Mae Ngai; Foreword by Hua Hsu. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.