IntroductionMy Natural Hair JourneyI didn't know my “naps” were tiny curls until my late twenties. Since I wasn’t blessed with “good hair,” I don’t recall ever hearing the word

curly being used to describe my tightly coiled texture. Just “nappy,” which, back in the 1990s, definitely wasn’t a compliment.

I learned early in life that my “bad hair” required a remedy. One such remedy came in the form of heat. I have vivid memories of Saturday night hot comb presses and holding on to my ears to shield them from getting burned. I remember the smell, the anxiety, and the result: straight hair that was deemed presentable for church on Sunday.

The more permanent solution for my “unwanted” texture required chemicals. I don’t remember my first hair relaxer, but I know it was applied pretty early in life. So early that I recall little to nothing about the head full of kinky hair that existed prior. After the cycle of regular relaxers began, my only interaction with my textured hair occurred when the troublesome “new growth” appeared and needed to be “touched up” with more relaxer. This routine conditioned me to dislike my hair in its natural state—the way it grew out of my scalp. I was taught to fix it, to alter it, to make it lay down and behave. I had no concept of any other way to treat my natural hair. I was only made to understand that it was not welcome.

One of my earliest memories of the extent of this conditioning is of a nine-year-old me, looking into the mirror after a full day of swimming. My skin had darkened from hours in the California sun and the edges of my hair were shriveled from exposure to the chlorinated water. I hated my reflection so much that I swore to never swim again.

Similar to many Black women, I was the recipient of generation upon generation of indoctrination about how my hair should look. My mother, grandmother, and mothers before them didn’t escape it, so neither did I. My grandmother had to get her hair pressed regularly when she was young because she was told she didn’t have “good hair” like her sister. My mother has expressed the desire to embrace her natural hair, but still feels societal pressure to keep her hair straight. This same pressure led her to decide to relax my hair before I was old enough to know the difference.

Growing up, I was surrounded by television shows, advertisements, and music videos that reinforced the idea that light skin and long, straight hair equaled beauty. Absent from my youth were mainstream representations of kinky-haired women presented as love interests or women in professional work environments. Years of anti-Black programming opened the door to subconscious self-hate in the form of my reliance upon heat and/or chemicals to keep my hair straight.

It wasn’t until the natural hair movement that I began to see my natural hair in a different light. Reminiscent of the “Black Is Beautiful” movement of the 1960s, the natural hair movement of the mid-to-late 2000s opened my eyes to the possibility that natural hair could be normal. While the movement began in the U.S., it spread throughout the diaspora—anti-Blackness and anti-kinky hair is a global issue, not just a U.S. issue. Many Black women started walking away from perms (relaxed hair)—some were motivated by a desire to prioritize the health of their hair, and others were inspired by the freedom that the natural hair movement offered. Either way, those who chose to go natural inevitably had to learn how to tend to their hair, some for the very first time. Thanks to social media, Black women were able to share and watch instructional videos, purchase products made specifically for their textures, read blogs depicting the journeys of fellow naturalistas, and publicly commune with one another about their hair. Thousands of natural hair blogs and vlogs were started in order to usher Black women toward the natural hair lifestyle. Black women no longer had to feel alone if they wanted to try natural hair. They were able to find communities of women online who were doing the same thing. Furthermore, through this virtual community, an entire culture was created where natural hair took center stage and self-acceptance was the goal.

This movement inspired me to question what I had grown up believing about my hair. Is my natural hair really unpresentable? Unprofessional? Unacceptable? No. I took a closer look at the prevailing beauty standard and realized it was never meant to include me. I realized that I don’t require fixing, alteration, or assimilation. I began to see that nappy has always been beautiful. So, in 2008, I cut off all of my relaxed hair and started my natural hair journey.

My decision to let my coils loose was the first step. The very next one included learning how to care for them. My big chop introduced me to my natural hair for the very first time. This meant I had no idea how to wash, detangle, condition, style . . . nothing. So, I, like many Black women during the early days of the most recent natural hair movement, turned to YouTube, natural hair blogs, and friends who had already made the transition. My community helped me figure out the process that would eventually become my regular ritual of self-care.

My natural hair journey is a continuous one. Having learned to embrace my hair, I am now passing the baton to my daughters. Even though my daughters have only ever seen me with natural hair, attended a predominantly Black pre-school, and had many Black aunties to look up to, White supremacy in the form of the hair texture hierarchy still managed to reach my oldest daughter when she was in kindergarten. I vividly remember the day she told me she wanted “White hair.” She asked, “Why doesn’t my hair lay down and swing around?” I knew at that moment that I had to be more intentional about ensuring both my girls learned about the value and beauty of their unique hair textures. I have the privilege of doing my part to ensure the “good hair/bad hair” lie surrenders its power. I’m continuously teaching my daughters about the origins of that lie, the current iterations of that lie, and ultimately, how to live free of that lie. I get to break the cycle. Today, both of my girls proudly show off their afros.

I’m certainly not an anomaly. The natural hair movement and the continued normalization of natural hair textures has not only impacted me, but many other Black mothers as well. So many of us have learned to accept ourselves more fully, and, in turn, are able to teach our children to do the same. We are now more informed about why we grew up thinking our hair was ugly. We have a better understanding of where these negative views of ourselves came from. We can see that these views are steeped in racism. We know that anti-Blackness is the culprit, not Blackness itself. In turn, we are equipped to teach our children the roots of racism and texturism, which is the idea that straighter hair is more beautiful or desirable than kinkier hair, so that they hopefully do not internalize the myths that keep these “isms” alive. While our children will likely continue to contend with non-inclusive beauty standards, we are putting them in a better position to understand and eradicate them.

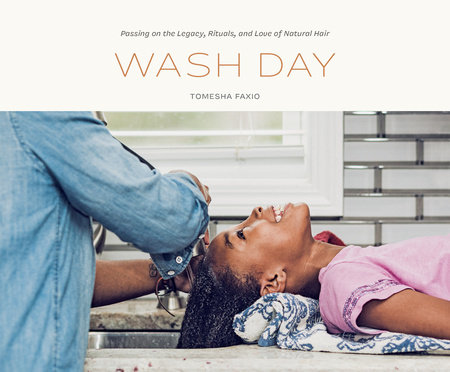

As a photographer, reflecting on my natural hair journey, and likewise, the collective journey Black women have been on with their hair for centuries, I knew I wanted to capture the significance and beauty of this moment in Black hair history. I want to tell the natural hair stories of Black women and show how we are continuing our journeys through our children. I could not think of a better way to illustrate this generational story than through the ritual commonly known as wash day.

Copyright © 2024 by Tomesha Faxio. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.