Introduction In September 2017, Hurricane María slammed into Puerto Rico, the most powerful storm to hit the island in nearly a century. The devastation was widespread and deadly; the storm killed thousands of Puerto Ricans and left millions more without water or power for months.

But in the wake of that catastrophe emerged hope. A group of chefs, cooks, delivery drivers, community leaders, and relief coordinators—loosely led by Chef José Andrés and his nonprofit organization World Central Kitchen—banded together to cook thousands, then tens of thousands, then hundreds of thousands of meals a day to feed the island. They called themselves Chefs For Puerto Rico.

Fast-forward five years to 2022, nearly to the day, and it was raining in Puerto Rico. Hurricane Fiona had spun over the island as a Category 1 storm, but gained strength frighteningly fast and dumped more than thirty inches of rain on parts of the island. Power and water were gone. Again.

And the chefs were back.

It wasn’t the circumstance that they would have wanted to mark the anniversary of their original heroics, but there they were, stationed around huge pans of arroz con pollo. The legion, spread across San Juan in the north and Ponce in the south, was larger now and worked with an efficiency born of the experience of having done it before. Many of the faces were familiar—Yamil López, Yareli and Xoimar Manning, Roberto Espina, Christian Carbonell, Manolo Martínez—and many were new. They quickly generated enough energy to meet the urgency.

Those chefs weren’t the only familiar faces.

In 2017, Ricardo Omar Colón Torres (pictured with José on page 15), whom the team took to calling Ricardito, showed up every day for weeks to help support the team’s operations. Ricardito was twenty-two and has a rare genetic developmental condition, and he volunteered to do every job he was given. He put WCK stickers on meal lids, he built boxes to transport those meals, and he handed out bottles of water to people waiting in line. If there was a job to do, Ricardito did it to perfection with an eye for detail that kept everything moving at peak efficiency. His mom, Iris, volunteered, too, helping distribute meals to their community on the outskirts of San Juan.

And in 2022, Ricardito and Iris were back, once again helping out with the operation.

It’s a devastating reality that Fiona replicated the pain and loss caused five years earlier by María, wiping out infrastructure for extended periods. It was the worst kind of déjà vu. But with the bad there was also hope, a silver lining to the storm’s dark clouds. An immediate start, with the team making sandwiches before the storm even passed, meant people were getting fed faster. And a reunion of the team with volunteers like Ricardito and chefs like Yareli and Roberto was the fuel needed to power through. So, sure, history repeats itself, but the happy parts repeat along with the difficult ones.

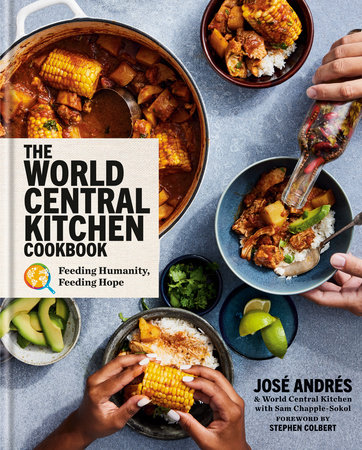

The span from when Hurricane María hit Puerto Rico in 2017 until Hurricane Fiona hit in 2022 provides a microcosm of the work World Central Kitchen does around the world, offering people the healing power of food and goodwill in a moment of crisis. It also provides a timeline of sorts for this book, which is a collection of recipes and stories about people we have encountered and worked with over those five years, in locations from Puerto Rico to Port-au-Prince, Caracas to Kyiv, and virtually every corner of the world. These recipes and stories contribute to what we know as a universal truth, that food has the power to change the world, one plate at a time.

But let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves . . . the story of World Central Kitchen starts well before Hurricane María.

Origins The year was 2010, and José was near the top of his game. He had ten popular restaurants around the US. He’d been named Best Chef in the Mid-Atlantic by the James Beard Foundation and was well on his way toward an Outstanding Chef nod a year later. The year prior, he was named

GQ’s Chef of the Year. Yet the most important award that José had received to date was the Vilcek Prize.

The Vilcek Foundation’s mission is to celebrate the lives and work of immigrants in America and it awards two prizes annually: one to a biomedical scientist and the other to someone in the sphere of arts and humanities. José is one of only two people to be honored for the culinary arts; chef Marcus Samuelsson, a longtime friend and Frontline Advisor of World Central Kitchen, is the other.

The prize included a $50,000 check, no strings attached. José’s career was on the rise, but he was far from wealthy. He and his wife, Patricia (Tichi), had three young daughters, and the rapid growth of the restaurants had left him stretched thin. But he and Tichi didn’t even have to discuss what to do with the money; they decided to put the entire prize toward funding a new nonprofit with the goal of changing the world through the power of food.

José had just visited Haiti in the aftermath of one of the deadliest earthquakes in history. He traveled with CESAL, a Spanish nonprofit organization that advocates for cooperation and social action, and they brought solar cookstoves to cook meals without electricity. It was also a chance to learn about the realities on the ground after a disaster of such immense magnitude. He quickly realized that he—and his entire profession of cooks—could be doing more. Having spent years volunteering in and around Washington, DC, notably at Robert Egger’s DC Central Kitchen, José decided he wanted to get involved in Haiti’s rebuilding by applying his skills to develop new ways to feed the world. His initial idea, based on the early work he had done with CESAL, was to introduce solar cookstove technology to Haiti.

José started talking to his longtime business partner Rob Wilder about launching a new organization to fulfill that dream. Rob and José had worked together for years: Rob had originally hired José in 1993 to work in a newly developed Spanish restaurant, Jaleo, which introduced tapas to downtown Washington, DC. Over the years, Rob, José, and their original partner, Roberto Alvarez, built a handful of concepts in DC and beyond: Café Atlántico, minibar, Zaytinya, and Oyamel, to name a few. These restaurants, and José’s burgeoning identity as a culinary prodigy, led to the accolades of the 2000s.

Rob Wilder and his wife, Robin, matched José and Tichi’s donation, so the project—which they named World Central Kitchen, inspired by the hometown heroes—had $100,000 to get the work started. (According to Tichi, José walked around with the actual Vilcek Prize check for $50,000 in his wallet for months before cashing it!)

José and Rob brought on Javier Garcia, a lawyer and food importer whom José knew from DC’s Spanish community. Javier had recently started his own non-profit and was familiar with the process—vital for navigating the legal challenges of creating a new NGO.

The three of them brought on Fredes Montes (pictured left), a World Bank financial specialist, as executive director, and put together a passionate board of directors, including Robert Egger, and an advisory board full of experts in multiple disciplines: disaster relief, technology, agricultural development, economics, solar energy, and more. With the seed money, a solid structure, and the motivation to create positive change in Haiti, the small team got to work.

Copyright © 2023 by José Andrés & World Central Kitchen with Sam Chapple-Sokol. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.