IntroductionI went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately. —Henry David Thoreau

Here is the beauty of walking deep into the woods: you see small moments with great clarity. This is particularly true when I spend the day foraging in the forests of the Columbia Gorge or Mt. Hood. When I forage, I do so on private land and always with permission. I have no destination in mind; rather, I am on a treasure hunt. I might look for a grove of Douglas fir, beneath which cherished chanterelles sprout. Or I might search the forest floor, looking for dead limbs decorated in gray-green lichen.

Whatever the path, this walk is a visual adventure. I am looking for the odd twist in a leaf, a branch still bearing its acorns, a mushroom sneaking its head out from under softened moss. Each is a design element, something I might use as inspiration for a forest-themed still life that will grace my dinner table or decorate a quiet corner.

In the past decade, I have fallen in love with old-growth woodlands that renew themselves by shedding old limbs and shading rocky trails with moss and fern. These are woods untended by humans, where the process of birth, death, and renewal follows the seasons. I have always been a woods-walker, but since I began gathering bits of the forest to create one-of-a-kind arrangements, I have found myself walking more deliberately. Each forest excursion becomes an experience in itself, when time stops and Nature takes over.

Many of you will know what I am talking about. Especially during the hard days of the pandemic, people needed respite from their isolation, a sense of life continuing. That’s why so many of us wandered outdoors. Many took a page from the Japanese tradition of Shinrin-Yoku, or “forest bathing.” It’s the practice of immersing yourself in Nature in a mindful way, using your senses to relieve anxiety and lower stress.

“In every walk with Nature, one receives far more than he seeks,” wrote environmentalist John Muir. That’s how I feel when the sun slants through trees on a late-spring afternoon and I spy a fragile blossom or discover a fledging nest. I am well-nourished by these forest walks, harvesting peace and tranquility as well as inspiration for my woodland projects.

My Woodland JourneyI grew up in Belgium, an active child, with parents who were avid Nature lovers. From the time I was six to age ten, we would spend a month each summer hiking in the Swiss Alps. Every year, my parents chose a village in a different region, each one storybook beautiful, with bright flowers cascading from tidy balconies.

In the evening, my father pored over maps of hiking trails, choosing one for the next day that promised magnificent views. My mother packed our lunches, and we would be off with the morning light, often hiking above the timberline. We climbed high enough to see whole valleys from our rocky purchase, pausing for photos in front of melting glaciers. Our visual appetite sated, my family would descend to a patch of forest green, where we relaxed during long lunch breaks. Often, my siblings and I wandered into the woods, found an unusual piece of bark, draped it in moss, and added a collection of wildflowers, proudly presenting the final arrangement to our mother.

Fast-forward forty-five years. I was married, living in Portland, Oregon, and—still smitten by Nature—earning my living as a successful floral designer. I casually mentioned this alpine memory to a photographer and art director, while we were shooting photos for a book proposal. They suggested I create one of my woodland pieces for the photo shoot. Though I doubted they would use it, I found a lichen-covered log and decorated it with curly kiwi vine, a selection of seedpods, foliage from my garden, some store-bought succulents, and a variety of acorns. The resulting photographs were beautiful. Two months later, a bride—her fiancé’s name was

Woods—asked me to create a series of log motifs as table decorations for her wedding.

That was my woodland journey. One wedding assignment led to another and my work was being published in national and international magazines. I began creating unique still lifes for special events. I began teaching woodland design workshops and even developed an online course.

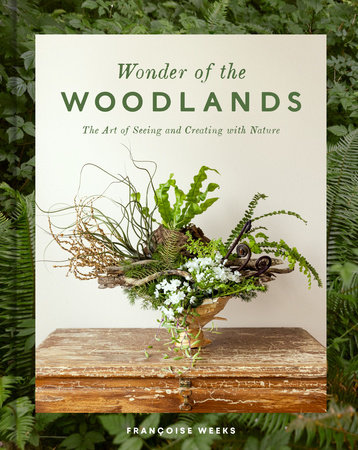

However, you don’t have to live in the woodlands to make a woodland arrangement. In fact, most of the materials I use are from nurseries, flower markets, craft stores, and grocery stores. This book is the next step in showing people how they can gather inspiration from Nature to construct their own artful arrangements. Pay attention to the beauty found on your own walks in the woods—a log, tiny pinecones, a handful of young acorns, wild rose hips, or shapely seedpods. No one’s inspiration will be the same; it depends on the seasons and where you live. Whatever the elements, the goal is to create a still life that captures a moment in Nature.

I’ve divided this book into chapters, each one illuminating a common building block in my arrangements, and each suggesting simple projects with steps to follow as well as many other projects that may inspire you. Since bark, logs, and branches form the backbone of my designs, I begin there, followed by chapters on mosses, mushrooms, acorns, lichens, and ferns.

I’ve included a list of tools and some instructions for how to make unique arrangements. But my primary goal is to teach you to see the artistry contained in any natural landscapes—be it ferns reaching up from the forest floor or acorns scattered through moss. I want you to see with a new pair of eyes.

How I SeeAs a floral designer, I had always focused on flowers, my gaze drawn to the perfect blossom. When I switched my focus to woodland design, I started to look at everything in the garden and in Nature from a different perspective. I paid more attention to the beautiful foliage of annuals, perennials, herbs, ground covers, and vines, incorporating them all into my designs. Checking for interesting seedpods of any plant became a new focus. Sometimes the beauty of a bud in my garden would catch my eye and I would snip this newly found treasure well before its bloom.

Rather than weed out the invasive wild strawberries that wandered among my sedum, I would harvest them to add whimsy to an arrangement. When pruning trees or shrubs, I would carefully gauge how usable the pieces would be in building a structure. I’d see a hollowed-out stump and wonder how I could repurpose it as a moss-covered “container.” I memorized which trees grew where in my neighborhood, so I knew where to collect acorns and other seedpods when they dropped to the sidewalk. I’d seek out golden ginkgo leaves and other vibrant foliage while walking to the supermarket. My new eyes began to see beauty in the curling bark of a birch tree or the spore-laden bend of an autumn fern.

Gone are the days of hiking fast through the woods; now I wander with my eyes on the forest floor. During these stop-and-start rambles, I will gather the many varieties of pinecones, acorns, and lichens that I use in my still life arrangements. But I am a careful forager. Though I hike for inspiration on public land, I do most of my collecting in woods that are privately owned and where I have the owner’s permission.

I am blessed to live in a city of parks and a state known for its dramatic coastline and farmlike country lanes. When I walk along Pacific beaches, my eyes are drawn to driftwood that I gather where it’s allowed and use it in my work. I look, too, for seaweed that I soak, shape, dry, and weave into arrangements. Once you begin to spy items for your own forest still lifes, you’ll find that every walk is an opportunity to find inspiration.

Copyright © 2024 by Françoise Weeks. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.