IntroductionMidtown Manhattan in the 1970s was not a culinary mecca.

On my block (Fifty-Fifth and Seventh Avenue) we

did have the Carnegie Deli (Dad always got liverwurst sandwiches) and a bunch of quality coffee shops (where Mom ordered her grilled cheeses). I ate so many cheeseburgers growing up that my mother asked if I would ever care about food on any level . . . oh, the irony. At home, we cooked. A lot. Usually whatever protein was in excess and marked down that week at the store, like “London Broil” steaks (which could’ve been any number of beef cuts). My dad would heat a pan until it literally warped from the heat and the handle melted slightly. Then he would drop the steak in (without oil) and watch the pan turn every shade of gray to black. He would flip the steak and then open the front door to the hallway of our building as if it was a step in a recipe. Sometimes the smoke alarm for the whole floor would go off. Along with the steak, we ate frozen Birds Eye vegetables that my dad painstakingly heated with sugar, salt, and pepper. Or his doctored (shredded) green beans. Or his gently warmed lima beans. I loved the starchiness of those beans. They enabled me to pick out the virtues of salt, pepper, and sugar early on. My dad would put Walter Cronkite on the black-and-white Sanyo TV with a broken antenna. My mom would breeze in with a stack of cookbook manuscripts, and we ate, silently, in four minutes flat. I was growing up American for all I knew. Except for one small thing.

My dad made tomato sauce as if he were auditioning to run the Pentagon. Canned tomato paste and canned tomatoes (never fresh), oregano, garlic and garlic powder, and tons of salt were in the mix. Onions. A generous dose of sugar. A quick simmer. “My sauce is better than Mom’s, eh?” he would semi-ask and semi-tell me, nudging me with his elbow and stirring the sauce. “Yes, Dad, it’s better, but don’t tell her,” I’d whisper diplomatically. The tomato sauce meant more to him than any other thing he cooked. We ate it on pasta, on meat, and even on rice. It permeated a lot of our dinners. It was the one thing I associated with being Italian.

On weekends when Mom had more time, she’d make “her” tomato sauce with grated carrot, onion, and garlic quick-cooked in olive oil, with canned tomatoes (again, never fresh) and salt. She’d let it simmer for a spare twenty minutes and then spoon it over the pasta. “I think your father puts too much tomato paste and sugar in his sauce,” she’d mutter as the food processor whirred. “Don’t you?” she would ask me. Murky waters. My mom’s maiden name was DiBenedetto and my father’s side was all named either Guarnaschelli or Spinicelli. I was surrounded by temperamental Italians. “Your mother is from Sicily . . . Calabrese,” my neighbor Fran informed me with a sacred nod. Those words made my mom seem slightly more dangerous even though I had no idea what they meant. “Yes, Ma,” I’d tell her gently, “your sauce has so much more flavor than Dad’s.” Truth is, I felt bad for her because I felt my mom really needed “the win.”

Each of my parents’ sauces became an expression of their personalities. My dad whipped up an umami bomb by tinkering with many ingredients and letting them slowly come together, while Mom went for the simplicity of the vegetables to thicken and flavor her comparatively straightforward and quick recipe. Her sauce tasted pleasantly grassy and slightly raw in the best way, while Dad’s was vibrant, tomatoey, and acidic in the best way.

When we ate out, wandering a few blocks west to the many small restaurants that littered Hell’s Kitchen on Ninth Avenue, it was exciting. We frequently ate volcanically hot ziti or overly ricotta-ed lasagna, and I loved those meals, too. I learned how much I value the baked-forever-in-an-extremely-hot-oven taste. I expanded my knowledge of red-sauce-joint dishes past what my parents shared, and it honestly is the biggest food memory I have from growing up. It made my parents emotional, too. One time, my dad got into a fistfight with about a dozen people over some cannoli in front of Ferrara bakery, and my mother would go to the other end of the Earth and spend money we didn’t have on a single bottle of balsamic vinegar (the good stuff). When she bought a pricey one at Dean & DeLuca, my dad didn’t speak to her for almost a week. Over a bottle of vinegar! My dad was prepared to die on that hill.

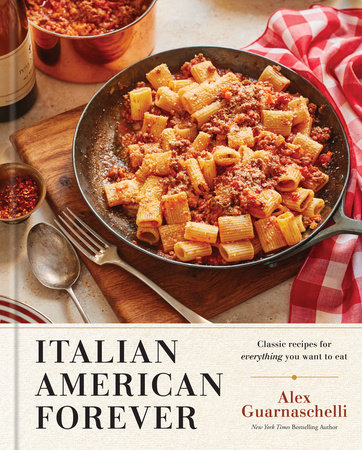

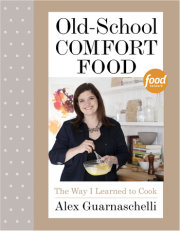

I think this book is a chef’s expression of classic red sauce dishes that have always been an integral part of New York City culture and, therefore, my life growing up here. This book is an exploration of my heritage and, strangely, dishes I have rarely, if ever, cooked in a restaurant. They are the dishes we make again and again to perfect them. They are the dishes we eat again and again because we crave them endlessly. Suffice to say, this book is from my heart, but it’s also likely already in yours. I almost called this book

Things People Always Want to Eat. I’m hoping that you’ll agree when you cook your way through it.

Copyright © 2024 by Alex Guarnaschelli. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.