The letter arrives on a Friday. Slit and resealed with a sticker, of course, as all their letters are:

Inspected for your safety-PACT. It had caused confusion at the post office, the clerk unfolding the paper inside, studying it, passing it up to his supervisor, then the boss. But eventually it had been deemed harmless and sent on its way. No return address, only a New York, NY postmark, six days old. On the outside, his name-Bird-and because of this he knows it is from his mother.

He has not been Bird for a long time.

We named you

Noah after your father's father, his mother told him once.

Bird was all your own doing.

The word that, when he said it, felt like him. Something that did not belong on earth, a small quick thing. An inquisitive chirp, a self that curled up at the edges.

The school hadn't liked it. Bird is not a name, they'd said, his name is Noah. His kindergarten teacher, fuming: He won't answer when I call him. He only answers to Bird.

Because his name

is Bird, his mother said. He answers to Bird, so I suggest you call him that, birth certificate be damned. She'd taken a Sharpie to every handout that came home, crossing off

Noah, writing

Bird on the dotted line instead.

That was his mother: formidable and ferocious when her child was in need.

In the end the school conceded, though after that the teacher had written Bird in quotation marks, like a gangster's nickname.

Dear "Bird," please remember to have your mother sign your permission slip. Dear Mr. and Mrs. Gardner, "Bird" is respectful and studious but needs to participate more fully in class. It wasn't until he was nine, after his mother left, that he became Noah.

His father says it's for the best, and won't let anyone call him Bird anymore.

If anyone calls you that, he says, you correct them. You say: Sorry, no, that's not my name.

It was one of the many changes that took place after his mother left. A new apartment, a new school, a new job for his father. An entirely new life. As if his father had wanted to transform them completely, so that if his mother ever came back, she wouldn't even know how to find them.

He'd passed his old kindergarten teacher on the street last year, on his way home. Well, hello, Noah, she said, how are you this morning? and he could not tell whether it was smugness or pity in her voice.

He is twelve now; he has been Noah for three years, but Noah still feels like one of those Halloween masks, something rubbery and awkward he doesn't quite know how to wear.

So now, out of the blue: a letter from his mother. It looks like her handwriting-and no one else would call him that. Bird. After all these years he forgets her voice sometimes; when he tries to summon it, it slips away like a shadow dissolving in the dark.

He opens the envelope with trembling hands. Three years without a single word, but finally he'll understand. Why she left. Where she's been.

But inside: nothing but a drawing. A whole sheet of paper, covered edge to edge in drawings no bigger than a dime: cats. Big cats, little cats, striped and calico and tuxedo, sitting pert, licking their paws, lolling in puddles of sunlight. Doodles really, like the ones his mother drew on his lunch bags many years ago, like the ones he sometimes draws in his class notebooks today. Barely more than a few curved lines, but recognizable. Alive. That's all-no message, no words even, just cat after cat in ballpoint squiggle. Something about it tugs at the back of his mind, but he can't quite hook it.

He turns the paper over, looking for clues, but the back of the page is blank.

Do you remember anything about your mother, Sadie had asked him once. They were on the playground, atop the climbing structure, the slide yawning down before them. Fifth grade, the last year with recess. Everything too small for them by then, meant for little children. Across the blacktop they watched their classmates hunting each other out: ready or not, here I come.

The truth was that he did, but he didn't feel like sharing, even with Sadie. Their motherlessness bound them together, but it was different, what had happened to them. What had happened with their mothers.

Not much, he'd said, do you remember much about yours?

Sadie grabbed the bar over the slide and hoisted herself, as if doing a chin-up.

Only that she was a hero, she said.

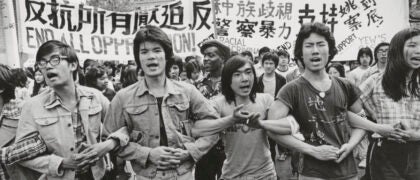

Bird said nothing. Everyone knew that Sadie's parents had been deemed unfit to raise her and that's how she'd ended up with her foster family, and at their school. There were all kinds of stories about them: that even though Sadie's mother was Black and her father was white they were Chinese sympathizers selling out America. All kinds of stories about Sadie, too: that when the officers came to take her away she'd bitten one and ran screaming back to her parents, and they'd had to cart her off in handcuffs. That this wasn't even her first foster family, that she'd been re-placed more than once because she caused so much trouble. That even after she'd been removed, her parents kept on trying to overturn PACT, like they didn't care about getting her back; that they'd been arrested and were in jail somewhere. He suspected there were stories about him, too, but he didn't want to know.

Anyway, Sadie went on, as soon as I'm old enough I'm going back home to Baltimore and find them both.

She was a year older than Bird, even though they were in the same grade, and she never let him forget it. Had to repeat, the parents whispered at pickup, with pity in their voices. Because of her

upbringing. But even a new start can't straighten her out.

How, Bird had asked.

Sadie didn't answer, and after a minute she let go of the bar and slumped down beside him, a small defiant heap. The next year, just as school ended, Sadie disappeared-and now, in seventh grade, Bird is all alone again.

It is just past five: his father will be home soon, and if he sees the letter he'll make Bird burn it. They don't have any of his mother's things, not even her clothes. After she'd gone away, his father burned her books in the fireplace, smashed the cell phone she'd left behind, piled everything else in a heap at the curb. Forget about her, he'd said. By morning, people living rough had picked the pile clean. A few weeks later, when they moved to their apartment on campus, they'd left even the bed his parents had shared. Now his father sleeps in a twin, on the lower bunk, beneath Bird.

He should burn the letter himself. It isn't safe, having anything of hers around. More than this: when he sees his name, his old name, on the envelope, a door inside him creaks open and a draft snakes in. Sometimes when he sees sleeping figures huddled on the sidewalk, he scans them, searching for something familiar. Sometimes he finds it-a polka-dot scarf, a red-flowered shirt, a woolen hat slouching over their eyes-and for a moment, he believes it is her. It is easier if she's gone forever, if she never comes back.

His father's key scratches at the keyhole, wriggling its way into the stiff lock.

Bird darts to the bedroom, lifts his blankets, tucks the letter between pillow and case.

He doesn't remember much about his mother, but he remembers this: she always had a plan. She would not have taken the trouble to find their new address, and the risk of writing him, for no reason. Therefore this letter must mean something. He tells himself this, again and again.

She'd left them, that was all his father would say.

And then, getting down on his knees to look Bird in the eye: It's for the best. Forget about her. I'm not going anywhere, that's all you need to know.

Back then, Bird hadn't known what she'd done. He only knew that for weeks he'd heard his parents' muffled voices in the kitchen long after he was supposed to be asleep. Usually it was a soothing murmur that lulled him to sleep in minutes, a sign that all was well. But lately it had been a tug-of-war instead: first his father's voice, then his mother's, bracing itself, gritting its teeth.

Even then he'd understood it was better not to ask questions. He'd simply nodded, and let his father, warm and solid, draw him into his arms.

It wasn't until later that he learned the truth, hurled at him on the playground like a stone to the cheek:

Your mom is a traitor. D. J. Pierce, spitting on the ground beside Bird's sneakers.

Everyone knew his mother was a Person of Asian Origin. Kung-PAOs, some kids called them. This was not news. You could see it in Bird's face, if you looked: all the parts of him that weren't quite his father, hints in the tilt of his cheekbones, the shape of his eyes. Being a PAO, the authorities reminded everyone, was not itself a crime. PACT is not about race, the president was always saying, it is about patriotism and mindset.

But your mom started riots, D. J. said. My parents said so. She was a danger to society and they were coming for her and that's why she ran away.

His father had warned him about this. People will say all kinds of things, he'd told Bird. You just focus on school. You say, we have nothing to do with her. You say, she's not a part of my life anymore.

He'd said it.

We have nothing to do with her, my dad and me. She's not a part of my life anymore. Inside him his heart tightened and creaked. On the blacktop, the wad of D. J.'s spit glistened and frothed.

By the time his father comes into the apartment, Bird is sitting at the table with his schoolbooks. On a normal day he'd jump up, offer a side-armed hug. Today, still thinking about the letter, he hunches over his homework and avoids his father's eyes.

Elevator's out again, his father says.

They live on the top floor of one of the dorms, ten flights up. A newer building, but the university is so old even the newer buildings are outdated.

We've been around since before the United States was a country, his father likes to say. He says

we as if he is still a faculty member, though he hasn't been for years. Now he works at the college library, keeping records, shelving books, and the apartment comes with the job. Bird understands this is a perk, that his father's hourly wage is small and money is tight, but to him it doesn't seem like much of a benefit. Before, they'd had a whole house with a yard and a garden. Now they have a tiny two-room dorm: a single bedroom he and his father share, a living room with a kitchenette at one end. A two-burner stove; a mini fridge too small to hold a carton of milk upright. Below them, students come and go; every year they have new neighbors, and by the time they get to know people's faces, they are gone. In the summer there is no air-conditioning; in the winter the radiators click on full blast. And when the balky elevator refuses to run, the only way up or down is the stairs.

Well, his father says. One hand goes to the knot of his tie, working it loose. I'll let the super know.

Bird keeps his eyes on his papers, but he can feel his father's gaze pause on him. Waiting for him to look up. He doesn't dare.

Today's English assignment:

In a paragraph, explain what PACT stands for and why it is crucial for our national security. Provide three specific examples. He knows just what he should say; they study it in school every year. The Preserving American Culture and Traditions Act. In kindergarten they called it a promise:

We promise to protect American values. We promise to watch over each other. Each year they learn the same thing, just in bigger words. During these lessons, his teachers usually looked at Bird, rather pointedly, and then the rest of the class turned to look, too.

He pushes the essay aside and focuses on math instead.

Suppose the GDP of China is $15 trillion and it increases 6% per year. If America's GDP is $24 trillion but it increases at only 2% per year, how many years before China's GDP is more than America's? It's easier, where there are numbers. Where he can be sure of right and wrong.

Everything all right, Noah? his father says, and Bird nods, makes a vague gesture at his notebook.

Just a lot of homework, he says, and his father, apparently satisfied, goes into the bedroom to change.

Bird carries a one, draws a neat box around the final sum. There is no point in telling his father about his day: each day is the same. The walk to school, along the same route. The pledge, the anthem, shuffling from class to class keeping his head down, trying not to attract attention in the hallway, never raising his hand. On the best days, everyone ignores him; most days, he's picked on or pitied. He's not sure which he dislikes more, but he blames both on his mother.

There is never much point in asking his father about his day, either. As far as he can tell, his father's days are unvarying: roll the cart through the stacks, place a book in its spot, repeat. Back in the shelving room, another cart will be waiting. Sisyphean, his father said, when he first began. He used to teach linguistics; he loves books and words; he is fluent in six languages, can read another eight. It's he who told Bird the story of Sisyphus, forever rolling the same stone up a hill. His father loves myths and obscure Latin roots and words so long you had to practice before rattling them off like a rosary. He used to interrupt his own sentences to explain a complicated term, to wander off the path of his thought down a switchback trail, telling Bird the history of the word, where it came from, its whole life story and all its siblings and cousins. Scraping back the layers of its meaning. Once Bird had loved it, too, back when he was younger, back when his father was still a professor and his mother was still here and everything was different. When he'd still thought stories could explain anything.

Copyright © 2022 by Celeste Ng. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.