Chapter OneMountbattenLouis Mountbatten rose at his usual time, just before 8:00 a.m., to a heartening vista outside his bedroom window. An azure sky unfurled over the Atlantic. After weeks of rain and foaming seas, the old man was finally getting sailing weather for the end of his Irish holiday. Mountbatten performed his calisthenics, a Canadian air force drill, and joined his family for breakfast in the dining room of Classiebawn Castle. He sent the poached egg back to the kitchen-the yolk was watery-but that didn't sour his mood. It was going to be a splendid morning for lobster potting.

It was Monday, August 27, 1979, and Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten was enjoying retirement. He was on the periphery of Europe, far from great events, no longer facing monumental decisions, and perfectly content.

Born in 1900, he had led a singular life that threaded the history of the twentieth century. His great-grandmother and godmother was Queen Victoria and his godfather Russia's Tsar Nicholas II. A naval officer and a favorite of Winston Churchill, he served as Supreme Commander of Allied Powers in Southeast Asia during the war and later became Lord Mountbatten of Burma and the last viceroy of India.

Dickie, as he was known to friends, was cousin to Queen Elizabeth and mentor to her husband, Prince Philip, and their son Prince Charles. Handsome, pompous, playful, exceedingly vain, Mountbatten had graced Europe's palaces and chanceries with movie star looks and scandalous gossip.

On this August morning, his glory years long behind him, his once-ramrod posture somewhat saggy, he bossed around the only people he still could: his family. The grandchildren didn't mind because, since they were small, Grandpapa had been a font of stories, rhymes, and games. "Nick'las, Nick'las, don't be so ridic'las," he used to say to one grandson. Then, turning to Nicholas's identical twin, Timothy: "Timothy Titus, please don't bite us," followed by a lunge and gnashing of teeth.

The grandchildren learned that if a wineglass was ringing, they must stop the reverberation because if it was left to fade into silence, somewhere a sailor would perish. Mountbatten also taught them the Bus Driver's Prayer, a parody of the Lord's Prayer that takes the driver around London:

Our Farnahm, who art in Hendon,Harrow be thy name.Thy Kingston come; thy Wimbledon,In Erith as it is in Hendon.Give us this day our daily BrentAnd forgive us our Westminster,As we forgive those who Westminster against us.Mountbatten had been coming to Classiebawn, which overlooked Mullaghmore, a village in Sligo on Ireland's northwest coast, for thirty summers. It was a turreted Victorian manor house, not a true castle, but had a fairy-tale look. A flat-topped rock formation, Benbulben, brooded over a landscape of fields, woodland, and beaches. Shipwrecks from the doomed Spanish Armada that had tried to invade England in 1588 dotted the seabed. "No place has ever thrilled me more and I can't wait to move in," Mountbatten had exulted after first visiting Classiebawn.

When not riding horses, writing letters, or playing board games, the old admiral would potter about the bay in his beloved

Shadow V, a twenty-eight-foot fishing boat. For weeks the weather had been spiteful, the worst in living memory, and the boat had languished unused in Mullaghmore's harbor. Now the sun had finally revived. With just a few days left before the family returned to London, Mountbatten planned to take advantage.

By the time the expedition members assembled in the courtyard, it was 11:15 a.m. Mountbatten crunched over the gravel to tell two Irish police bodyguards-Detective Kevin Henry, armed with a service revolver, and a uniformed colleague, Kevin Mullins, parked in their usual spot-of the outing. The family piled into a white Ford Granada for the short drive to the harbor, tailed by the policemen. Every radio station seemed to be playing the same song: "I Don't Like Mondays" by the Boomtown Rats.

Shadow V-green hull, cranky diesel engine, pungent little cabin-bobbed by the stone jetty. Mountbatten needed some help down the greasy ladder, as did his eighty-three-year-old mother-in-law, Lady Doreen Brabourne. The other crew members were his daughter Patricia; her husband, John Knatchbull; their fourteen-year-old twins, Nicholas and Timothy; and Paul Maxwell, a fifteen-year-old boat boy from Enniskillen in Northern Ireland. Lady Brabourne sat in the stern with Patricia, while the menfolk took posts on the bow and in the cabin. Mountbatten took the helm and guided Shadow V through the other moored boats.

"Astern!" Mountbatten called, opening the throttle and boiling the water beneath. The boat wheeled. "Ahead!" he called, and aimed for the open sea.

"You are having fun today, aren't you?" Knatchbull said, grinning, to his father-in-law.

Mountbatten did not reply.

Shadow V chugged toward lobster pots a few hundred yards offshore, churning foam in a flat green sea.

Maxwell asked the time, and Timothy looked at his watch: "Eleven thirty-nine and forty seconds." Timothy climbed onto the cabin roof to keep watch for fishing lines that could tangle the propeller, as he knew Grandpapa's eyesight wasn't what it used to be. "Buoy twenty yards ahead and slightly to port!" he called.

Mountbatten, silent, seemed lost in reverie. Maybe he was remembering the war-the sinking of his naval destroyer off of Crete, taking the Japanese surrender at Singapore. Maybe he was wondering if Britain's new prime minister would get on with the Queen. Maybe he was visualizing lobster for dinner.

"Isn't this a beautiful day?" said Lady Brabourne.

From a hilltop the police bodyguards kept vigil. They weren't the only ones watching.

• • •

Ireland’s tormented relationship with the English Crown was written into the Sligo landscape that so thrilled Mountbatten. A story of blood and soil was etched into mossy gravestones and crumbling ruins.

In limestone caves south of Classiebawn, Irish myth claims that the hunter Finn McCool once found a portal to another world. The quarrelsome Gaelic chieftains who ruled Ireland at that time must have wished he'd closed it before Anglo-Norman mercenaries clanked ashore in 1169 on a mission of conquest blessed by King Henry II of England, ushering in centuries of savage subjugation.

It was no accident, after all, that this archipelago off northwestern Europe would become known as the British Isles. Ireland lay on the western edge, the remoter, smaller neighbor of a powerful kingdom comprising England, Wales, and Scotland. Even on maps, Britain appeared to lean into Ireland.

Even so, the mercenaries never fully tamed Ireland's natives, the Gaels. The two sides intermarried and blurred into each other, complicating England's conquest of this troublesome island-the first colony in what would later become a global empire. The stakes rose after the reformation when, in the sixteenth century, England sloughed off the pope's religious authority. Under Henry VIII, England became Protestant, while the Indigenous Irish remained Catholic. This gave Spain and other Catholic powers a potential back door to England.

Not long after, in an effort to tame the especially rebellious northern province of Ulster, the English Crown confiscated Gael land and gave it to Protestant settlers, known as planters, from Scotland and England. The natives became outcasts, harried at the point of a sword from the land of their ancestors. When they fought back, massacring settlers, the English response was ferocious: Oliver Cromwell led an avenging army that slaughtered Catholics across Ireland and banished survivors to rocky, infertile soil, a campaign of ethnic cleansing that through violence and disease wiped out more than a fifth of the population. Others were banished overseas as indentured laborers. Some historians would later brand the whole enterprise genocide.

An underclass in their own land, scorned for their language and religion, the Irish still periodically rebelled. On occasion, Protestant radicals joined these doomed enterprises, but mostly they were Catholic affairs. All ended with hangings. Anglo-Irish nobles who sided with the Crown, meanwhile, were rewarded with large estates.

When potato crops failed in the 1840s, more than a million peasants died of starvation and disease in what became known as the Great Famine. Another million emigrated in so-called coffin ships. The historian A. J. P. Taylor, writing a century later, evoked a death camp: "All Ireland was a Belsen."

Queen Victoria's government limited food aid, lest charity foster idleness and other vices in what was deemed an inferior race, as if evolution had taken a wrong turn with these backward Celts in contrast to the eminently superior Anglo-Saxons. English publications caricatured the Irish as apelike brawlers, drinkers, and layabouts, a race predisposed to superstition, savagery, and indolence.

"The judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson," said Charles Trevelyan, a Treasury mandarin in charge of famine relief. "The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people."

Some saw opportunity. Agents for Lord Palmerston, a British statesman who owned ten thousand acres around Mullaghmore, hustled two thousand unwanted tenants onto ships. They landed in Canada, malnourished and half-naked, and many froze to death. Palmerston, oblivious, built Classiebawn Castle and erased a village, Mullach Gearr, to enhance the view. He put no markers to indicate a burial ground. According to legend, stepping on such grass condemned you to ravenous, insatiable hunger. It was feár gortach-Irish for "hungry grass"-but the language itself withered as survivors left rural areas and adopted English, the victor's tongue.

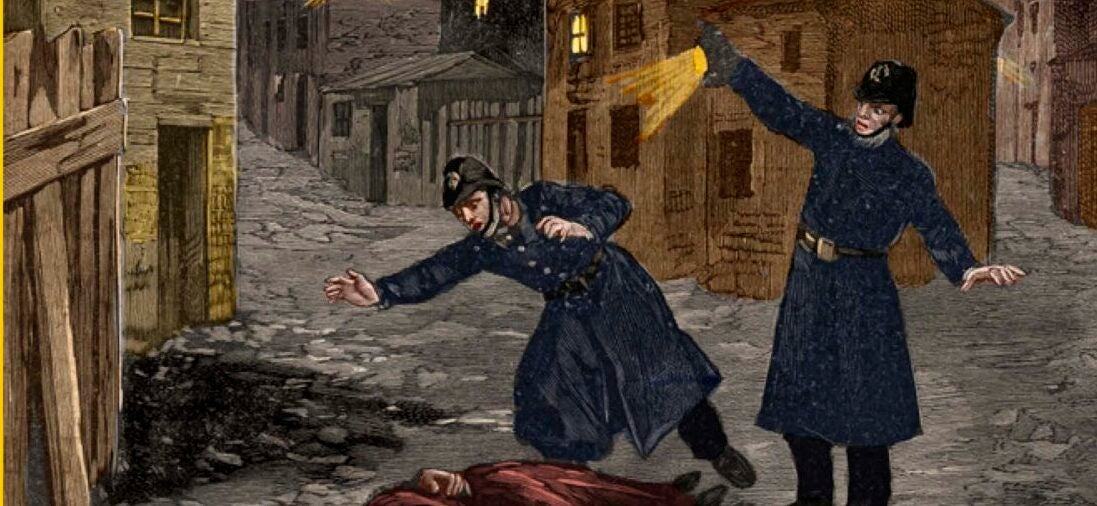

The catastrophe traumatized and embittered the natives. Small underground groups such as the Fenians and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) vowed to end British rule and create an independent Irish republic. They staged bombings and assassinations between the 1860s and the 1890s, to little effect. By now, the British empire straddled the globe and was not going to bow, as authorities saw it, to hooligans and terrorists. Peaceful political agitation proved more successful. By the outbreak of the First World War, moderate Irish nationalists who played the parliamentary game had extracted a promise from London for self-governance after the war.

For the revolutionaries, though, that was too little too late. In April 1916 they launched an insurrection in Dublin, Ireland's capital, and proclaimed an Irish republic. The Easter Rising was a military shambles with little popular support. British soldiers squelched it within a week, leaving the center of Dublin a smoking ruin. But then the authorities made a fateful blunder. They introduced martial law and executed rebel leaders, sixteen in all. These were seen as martyrs, and public sentiment radicalized. William Butler Yeats, who grew up near Classiebawn, immortalized the transformation in his poem "Easter, 1916."

All changed, changed utterly:A terrible beauty is born.Self-governance was no longer enough. The Irish wanted revolution. They rallied to Sinn Féin, a political party whose name meant "We Ourselves." Outside Protestant areas in the north, it swept the December 1918 election. Instead of taking its seats in the British Parliament at Westminster, the party proclaimed an Irish parliament, Dáil Éireann, in Dublin. Weeks later, a guerrilla force began ambushing police and soldiers around Ireland. Its name was the Irish Republican Army.

IRA units trained and hid arms within sight of Classiebawn Castle, by then owned by Wilfrid Ashley, a British aristocrat and Conservative member of Parliament. Sensing a turning tide, his family, including his daughter Edwina, Mountbatten's future wife, stopped visiting their summer home. By 1920, the ambushes had escalated into a war of independence. Under Michael Collins, a charismatic leader known as the "big fella," the IRA burned police stations. The rebels also destroyed the grand homes of aristocrats. Classiebawn was mined with explosives, but the local IRA decided to keep it intact to billet guerrillas and hold hostages.

Winston Churchill, then the British secretary of state for war, tried to regain control with an auxiliary force dubbed the "Black and Tans" for its dark and khaki uniforms. It acquired a reputation for atrocity. In response, the IRA escalated its own brutality. From 1919 to 1921, more than two thousand people died in the fighting. With neither side able to score a knockout blow, they agreed to a truce. Collins led a delegation to London and signed a treaty that created an Irish Free State, a self-governing dominion of the British empire, a status similar to Canada. British forces withdrew from twenty-six of Ireland's thirty-two counties. The remaining six northeastern counties formed a new entity, Northern Ireland, which could opt out of the Irish Free State.

It was a stunning achievement. Ragtag rebels had taken on the world's mightiest empire and won de facto independence. The Irish tricolor-green, white, and orange-would fly over Dublin. But some rejected the treaty. It would oblige Irish leaders to swear an oath to the Crown and risked partitioning the island. Where was the republic? The IRA split into pro- and anti-treaty factions and waged a bitter civil war. On August 22, 1922, a convoy carrying Collins was ambushed at a rural crossroads known as Béal na Bláth, Mouth of Flowers. The big fella tumbled to the road, shot dead by a republican purist. Weeks later his side executed and dumped the corpses of six anti-treaty IRA men on the slopes of Benbulben. The pro-treaty side eventually prevailed, formed an elected government, and later declared a republic.

Northern Ireland, however, remained part of the United Kingdom. Function followed form: the British drew the boundary so that Protestants, a minority on the island, outnumbered Catholics in the six counties. The Protestants considered themselves British, loyal subjects of the Crown, and refused to be absorbed into an independent Ireland dominated by Catholics. The UK now consisted of Great Britain-the island comprising England, Scotland, and Wales-and Northern Ireland. The descendants of the seventeeth-century planters took comfort in the border posts that mushroomed along the 310-mile border, separating them from the rebels, traitors, and papists to the south. Their provincial capital, Belfast, thrummed with industry, shipbuilding, and linen mills, and over it flew the Union Jack.

But the Catholic minority felt excluded and alienated. Many lived in slums, struggled to find work, and were not allowed to vote. The police were hostile. Sectarian riots fueled the bigotry. Many Catholics emigrated. Impoverished Ireland offered few opportunities, so they sailed to England or America. Most, however, stayed. They lacked the finances or temperament for exile, for the wrenching farewells and cold uncertainties. Northern Ireland, warts and all, was home. So they stayed, and quietly hoped things would get better. But discrimination endured.

The British government in London ignored the injustice. It wanted to forget about Ireland and its complicated disputes. Northern Ireland was a part of the UK, but a distant one. Successive governments in Dublin made pious declarations about unifying Ireland but did nothing about it. They were done with revolution and focused on turning their impoverished backwater into a nation state.

The only people who felt urgency about ending partition were aging republicans—who had been losers in the civil war—and some young apprentices bewitched by rebel ballads. In the 1940s and the 1950s, this motley crew of dreamers and gunmen tried to revive the IRA and staged sporadic attacks. Lacking public support on either side of the border, the campaigns fizzled. History seemed to swallow the IRA whole.

Then came 1969. Inspired by the US civil rights movement, Northern Ireland’s Catholics marched to end discrimination. Police clubbed them to a pulp. The marches turned into riots, and Protestant and Catholic mobs clashed. Streets went up in flames, Catholic refugees fled across the border, and the British government deployed the army to restore order. At first Catholics greeted English squaddies as protectors. The welcome evaporated in a haze of tear-gas and clumsy soldiering, and the army came to resemble another layer of oppression. Young men begged grizzled old IRA veterans: give us guns.

The Troubles were born.

Copyright © 2023 by Rory Carroll. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.