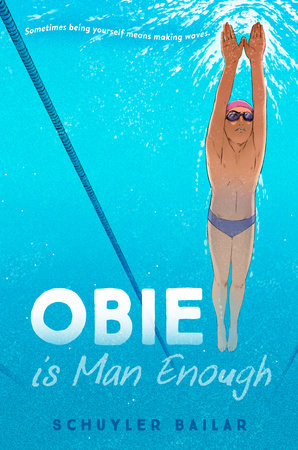

Chapter 1

“Take your mark”—a pause, and then the whistle blows. The guys dive into the water, splashing me and the others who are standing at the edge of the deck watching. Most of the team are at the other end of the lanes, cheering on the swimmers. Their bodies glow in the artificial light, the winter sun still sleeping.

“His butterfly looks like shit. How is he so fast?” Pooch laughs after the first lap. Pooch isn’t his real name. It took me a little too long to get that. It’s his last name, Puczovich, shortened. There was already a Samuel on the team when Puczovich joined, so everyone calls him Pooch.

“I know, man, I’m not sure,” I reply. “It’s pretty ugly, though.” We both stare at the guy in lane 8—Jackson. He grew about a foot last summer, no joke, and now his arms are too long for his own good. They drag in the water as he heaves them forward with each stroke. You’d think that with all that friction he wouldn’t go so fast, but he does. He’s already about half a body length ahead of Sammy—the original Samuel.

“Think he’ll die the last fifty like usual?” Pooch asks. I think about it for a second. Jackson does usually die, but he’s also a good amount ahead so—

“Why are you over here gossiping about your teammates instead of down there cheering them on? Do you want to be the next for a two hundred fly, Mr. Puczovich?” Coach stands right behind us, just a tad too close. She’s not very tall, but her voice makes us stand straight up.

“Sorry, Coach,” we mumble in unison and then shuffle off toward the other end of the lanes.

—

It’s been almost six months since I joined Coach Larkin’s group at Manta Ray Aquatics and I still haven’t decided what to make of her. She never yells at anyone for swimming bad races. She doesn’t yell much at all, really. When I didn’t go a best time at the first meet I swam for her, I’d hid in the warm-down pool for the better part of an hour, expecting her to yell at me like Coach Bolton would have. But she never did. She didn’t even come find me. When I returned to the team area finally, almost sulking, she didn’t even seem to notice.

Also, her practices have So. Many. Drills. And rest! We do rest days here! Coach Bolton would never have done that. I’ve been really worried that I’m not swimming enough yardage to be ready for upcoming meets. But Coach Larkin says everyone must at least start with trusting a coach’s method, especially when switching to a new team. So, I’m trying.

But I miss Coach Bolton. And somehow, unbelievably, I miss the yelling. How am I supposed to beat all of the guys without someone pushing me the way Coach Bolton did?

Jackson and Sammy are nearing the wall and Pooch and I lean down to yell in their faces as they do their flip-turns.

“Goooo!” we say together.

“Looks like he’s hanging in there,” I say to Pooch, nodding at Jackson. Coach is walking along the edge of the pool, shouting each time their heads break the surface. Every swim coach has a distinctive call, some more than others. Coach Bolton always used to make a big “BOO!” sound, deep and booming, emphasizing the ooo, that would carry his voice across the natatorium. You knew it was him. Everyone else on deck did, too, even the other teams. Coach Larkin’s yell is a higher-pitched, quick “HUP!”

I know it shouldn’t really matter, but I miss Coach Bolton’s “BOO!”

The whole team cheers as Jackson touches the wall a body length ahead of Sammy. Impressive.

“Obie and Mikey, two hundred IM.” Coach Larkin calls the next race.

“Aw, man, Coach L., why you gotta do me like that?” Mikey groans. “I don’t have energy for one stroke and you want me to do all four?” IM means “individual medley.” The 200 IM is a fifty of each stroke. I know he’s being intentionally dramatic so I don’t say anything aloud, but I definitely agree in my head. Plus, I already went; why do I have to go again? Also, against Mikey? Mikey is one of the fastest guys on this team.

“Miguel Garcia,” Coach Larkin says sternly. I’ve only ever heard Larkin call him that. I suppose his mom probably does, too. When he’s in trouble. “Get up on the blocks, boys,” Coach Larkin insists, a grin on her face. That’s another thing about Coach L., I think. Coaches aren’t supposed to smile.

“Take your mark—” My body tenses as I get into position. My mind goes blank. I take a deep breath, feeling the expected rush of adrenaline. This is one of the things I love about racing. It doesn’t matter how much you feel like you’ve got or how tired you are. Nothing else matters except this moment.

Two hundred yards. Let’s go. The whistle goes off.

The water crashes over my head as I pierce the surface. The world disappears for a moment beneath the rush of water. Here I am, I think. Here. I. Am.

I take six solid underwater dolphin kicks before I break for my first stroke. I don’t breathe, Coach Bolton’s voice in my head. You never breathe on the first stroke of butterfly or freestyle. Keep your head down. Air later.

Fly and backstroke laps go by in a blur. I grab armfuls of water, Mikey right beside me the entire way. I try my best not to focus on him, but I can feel the excitement building with every turn. I’ve been afraid of him since joining because he’s pretty well known in New England Swimming. The last time we raced each other, I hadn’t even had a chance. I’d lost by more than four seconds. Honestly, that’s nearly half a pool’s length. But today, I’m right with him.

Don’t get cocky, I remind myself. Breaststroke is my strongest. Focus.

Going into the last fifty, I am suddenly terrified I’ll burn out. I’ve gained a hefty lead—I’m almost a full body length ahead of Mikey. But freestyle is my weakest leg. The previous two hours of work hit me like a brick and my legs begin to burn. My lungs beg for more air. I answer them with a sharp no. I push off the wall, my mind clearer than it’s been in weeks. I collect myself as I hit one more underwater dolphin kick than usual. Seven. Here we go.

I pull farther ahead with each stroke. Mikey falls from my peripheral vision completely as I near the finish. I kick as hard as I can into the wall, diving for that last stroke, my fingers outstretched. I am grinning stupidly before I even raise my head from the water. I look up to see the team cheering. I beat Mikey Garcia! I. Beat. MIKEY GARCIA!

“Dude, where the heck did that come from—that was crazy!” Pooch is leaning over my lane, offering his fist. I bump it and realize just how sore my arms are. He steps over to Mikey’s lane and bumps him, too.

“Thanks, Pooch,” Mikey says, out of breath. “Wasn’t my greatest. . . .” He trails off, looking at his hands holding on to the edge of the pool. He seems a little disappointed, but then he turns to me, flashing a grin. He sticks his hand over the lane divider to shake. I’m suddenly shy.

“Nice job, man,” Mikey says. I hesitantly reach over, wondering why he doesn’t seem upset with me. Is the smile fake? But he looks earnest. How strange. Most of the guys in the ’Cudas would have been livid and screaming by now. Especially Clyde. They were all sore losers. Didn’t matter who they lost to. Although I think losing to me would kill Clyde. I shiver at the thought of his screaming.

“I’m pumped to race you at JOs this year,” he says. “It’s going to be dope.” Crap—JOs! Junior Olympics. I haven’t even dared to think about that meet.

“I mean, if I qualify,” I say anxiously, but still smiling.

“Oh, come on, Obes, of course you will. Next meet, we’ll throw down. Get you that cut.” Obes. That’s a new one. I like it. I make a mental note to add Mikey and Pooch to my journal list.

—

“So, munchkin, how was it?” Dad asks me as I hop in the car. He asks me this question every day after every single practice. You’d think he’d get bored. And yet, every time, he sounds genuinely interested.

“I told you, you can’t call me that anymore,” I say almost reflexively. But I’m too excited about practice to be annoyed. “We did some two hundreds off the blocks and my first was meh, like it was fine, I swam breast. But then Coach made me do IM against Mikey, of all people—I don’t know why—but then Mikey and me—”

“Mikey and I,” Dad corrects. I roll my eyes but I’m too eager to tell my story, so I just correct myself and keep going.

“Mikey and I had to do an extra two hundred IM and I was so tired, I thought I was going to pass out before I even got on the blocks, and Mikey was all pissed Coach made us do it.” I pause, catching my breath. I’ve always been a fast talker. Sometimes so fast that I forget to breathe. The only time it ever slowed was during That Year. Never mind. The race, I remind myself. “But I won! I went a 2:09.6, and he didn’t even break 2:10!” I grin from ear to ear.

“Wow, son, that’s fantastic! That’s so close to your best time, and just in practice.”

“I know. Mikey thinks that I can make the JO cut at the Invitational next month . . . but I’m pretty nervous and . . .” I trail off, my excitement quickly waning.

“O, I’m sure you’ll do great, but don’t worry about it now. You can’t control how the race goes when you’re not even in it. All you can do is prepare the best you can, and if you do that, you’ll put yourself in the best position to achieve your goals.” Some of Coach Dad emerges as he talks.

But my performance is not the only reason I’m nervous.

Everyone from the Barracudas will be there. Including Clyde.

The winter sun still hasn’t begun to peek over the horizon, but the sky has shifted to that early-morning dark blue as we drive home. It’s like a whole day passes during morning practice—filled with people and challenges that are entirely separate from the rest of the day.

Despite how difficult 4:30 a.m. practices can be, I absolutely love the feeling afterward. I’m up with a total running start. A swimming start! Haha. But really—I’ve already completed the most difficult task of the day and most people’s alarms aren’t even close to buzzing. So right now, I feel great.

I try not to think about the Invitational. Or Clyde.

Practice first. Race later.

Copyright © 2021 by Schuyler Bailar. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.