Home Home. A shelter with beds for all, a place to cook, eat, tell stories, do homework, store our clothes and books, hang our art, and use a bathroom. How can these simple ingredients have such an emotional tie on us? I think it is because home is embedded in the environment. Sounds are a profound part of that environment, especially natural ones. So I might say that birdsong defines home.

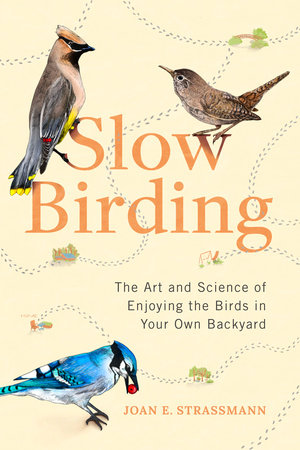

I'm likely to wake to the formal notes of Northern Cardinals, the policing cries of Blue Jays, the intense notes of Northern Flickers, or the chatter of House Sparrows. I slowly got to know the other birds of my home, the whistles of a passing flock of Cedar Waxwings, the hoarse voice of the Fish Crows nesting down the block, the clear repetition of a Carolina Wren, and the clicking sounds of a Cooper's Hawk. And there are others. Many others.

If you know the birdsong that defines your home, you can never lose it. If home becomes song, then no landlord can push you out. You can maintain the feeling of home. Though it might not include a bed, it will be somewhere you can revisit.

My home is in St. Louis, the city that opened the West and sold furs from the North to traders headed south to New Orleans down the Mississippi, from where they would be shipped to Europe. It is a city that has been important since Native Americans built the mounds across the river in Cahokia and also all through what would become northern St. Louis more than a thousand years ago. I like to say that St. Louis became big before America became selfish. This means we have a wonderful zoo, great museums, and state parks that have no entry fees.

My home is more precisely in an independent city adjoining St. Louis proper, called University City, founded as a planned city by the publisher, insecticide salesman, and shyster/visionary Edward G. Lewis. Lewis wanted to move his magazine publishing to a choice spot and had to buy the adjoining eighty-five acres to do so. He bought the land in 1902 and incorporated the city on September 4, 1906, with himself as mayor. His idea for the city was that it would follow the natural hills and valleys of the land, with minimal fill. The neighborhood to the north of us, University Heights, has curving streets and variably sized lots that fulfill that dream. Our street is in an area called West Portland Place and is a simple grid of streets, though the hills mostly remain.

In 1871 the eastern section of our street was named after the natal city of my father, Berlin. But in 1918 it lost that name because of strong sentiments against the Germans. The name of a military general, Pershing, was deemed more suitable. The efforts in 2014 to bring back Berlin as the street name failed.

Our house was built in 1921 of solid brick, three structural rows coated inside with plaster on a lot that's 50 by 135 feet. The clay that our bricks were fired from was dug locally, probably from within three miles of the house, perhaps from pits in Dogtown. The thick walls help our home stay warm in winter and cool in summer. It has giant radiators because it was built soon after the 1918 flu epidemic. Some then thought that keeping windows open was good for health, and the radiators had to keep up.

We wanted to make this small piece of St. Louis as wild as possible. First we dug a small pond, with a deep end of three feet and a shallow end where the toads could easily hop out. We surrounded it with slabs of native limestone and put a row of limestone boulders to curve across the back, separating a wild meadow from our vegetable garden. We planted the slope in front and the curb strip with little bluestem and other grasses, with asters, echinacea, and other prairie plants.

On one side in front we planted blueberry bushes. I imagined children going to Flynn Park Elementary two blocks away plucking a blueberry or two to suck on, though the blueberries ripen long before school opens in fall. Or they might pick a brown-eyed Susan for their teacher. In the fall our little hill turns purple with asters. American Goldfinches hang from drying flower heads picking out the seeds.

There is a patio in back where we eat in the summer at a metal table my sister handed down to me. It is shaded by a native dogwood that an American Robin nested in last year. Under it is bloodroot, columbine, and wild ginger. To the west is that small pond we dug, now inhabited by goldfish, toads, dragonflies, and other animals. Once a Great Egret and a Little Blue Heron visited it, and I have a photograph to prove it. Around the pond are cattails, irises, blazing stars, and ever more rudbeckia. In the summer Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and American Goldfinches flit through the plants. In the winter Northern Cardinals show red against the bare branches, and the American Goldfinches have lost their brilliant color.

The heart of the backyard is my vegetable garden. I grow mostly leaves and herbs, along with tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, beans, squash, and okra. The squash is mostly for the blossoms, which I stuff, dip in batter, and sizzle in olive oil. The leaves include mustard greens, collard greens, kale, arugula, and lettuces. Herbs are rosemary, sage, lots of basil, parsley, oregano, thyme, tarragon, and cilantro. Mint is kept in the front because it is too aggressive and would take over the garden the way the lemon balm is doing. I also have garlic, both for the heads and for the sprouts.

On this summer day, the House Wrens are going in and out of the nest box my husband, David Queller, gave me for my birthday in May. It is mounted in the backyard on a concrete post with a hook on top left over from a clothesline, whose other end once attached to a similar hook coming out of the garage. The male wren sat on the electric wire running just above the nest box to our house. He trilled away, clearly unhappy that I was picking pole beans only feet from his nest.

A Carolina Wren sings from the ridgeline of our neighbors' garage, maybe twenty feet from this nest box. These neighbors, Jay and Pam, are good friends. We have both House Wrens and Carolina Wrens in our backyard. I have seen them scuffle in the elderberry on the edge of our patio. But Carolina Wrens choose more open places than boxes for their nests.

Starlings nest under the eaves of the home Holly and Curtis bought a couple of years ago just to the west of us. From the thick layer of white droppings outside, I guess that nest was successful. Also, right after they fledged I often heard the dry buzz of begging juvenile starlings.

Every day there is something going on with the birds at home. There is the day the Northern Flickers urge their babies out of the nest with repeated long calls. There is the day the same flickers fail to chase the starlings out of the hollow across the street and have to find another down the block. There is the ongoing tension between Carolina Wrens and House Wrens. Does it matter that one migrates and the other does not?

In winter we have Dark-eyed Juncos and White-throated Sparrows with their mournful song. I saw them at home for the last time this year on April 8. They had been here since October 24. The White-throated Sparrows were here for longer. I last saw them on May 15 at nearby Heman Park. I first saw them at home on October 24.

We put out feeders of sunflower seeds, peanuts, and suet in the winter. The sunflower seeds that fall to the ground attract these three species. The suet brings in the Downy Woodpeckers and the Northern Flickers, when the European Starlings are not in the way.

I've talked about some of the birds in our small yard. I looked at what I have logged on eBird and saw I have logged seventy-three species right in my own garden.

Keeping a journal of the birds at home helps. Here is a section of mine.

April 18, 2020: The chimney swifts are back! Saw about 6 of them pivoting over our house. April 19, 2020: The juncos are gone. When did I see the last one? I always know the first. But when was the last? Lots of evening drama. A pair of flickers tried to take over the starling hole in the tree across the street. The flickers copulated, and then the male flew off. The female stayed at the hole, staring down the starling. She did not move. I only could see her sharp yellow beak. The flicker sat at the hole. The male starling fluttered a few meters above. The flicker stayed maybe 20 minutes, then moved up the trunk and to the side. Across the street a Cooper's Hawk landed on Carol and Roger's house two doors east, then leaped over to the neighbors, the family that had the dream of grandparents down the block until he took an unfortunate medicine, went on oxygen, then ultimately both went to a retirement center, where he finally decided to go off the treatments and died.

The hawk didn't know this. It jumped to the ground. We went back to watching the flicker until we went in for dinner. May 12: our daughter saw a Cooper's Hawk fly up from the pond. Was it hunting goldfish?Wherever your home is, learning the birds and what they do will help keep it in your heart forever.

Home Activities for Slow Birders

1. Create a home bird list. Start a list of the birds you see at home. Do it on eBird so that the world can benefit and you can easily pull it together. Ornithologists the world over use eBird from Cornell University's Laboratory of Ornithology to understand where birds are and how that changes with habitat and time. It is a record we can all contribute to. You might also want the satisfaction of a home bird journal. Just remember to write down the date, time, and weather for every observation. I record the temperature and whether it is sunny, cloudy, raining, or snowing. If you live in an apartment, you can list birds you see out the window or outside your apartment. The key thing is that you record what you see in one small, frequently attended place.

2. Install a bird feeder. Put out a feeder near your home or on your balcony. I usually put out peanuts, black-oil sunflower seeds, and suet. I add a hummingbird feeder when they arrive in the spring. In the winter I throw a couple of cups of sunflower seeds on the ground for the Dark-eyed Juncos, White-throated Sparrows, and Mourning Doves. I diminish feeding in the summer, when the birds can find natural food more easily. A feeder can work on a balcony. We had one on our balcony when we lived in Berlin for a year doing fellowships at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin. There we were able to attract the lovely Eurasian Bullfinch, along with Great Tits and others. It is really satisfying to pool your observations with those of others by joining the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Project FeederWatch (https://feederwatch.org). It has lots of advice on what to put in your feeders and how to watch the birds.

3. Put up a birdhouse for small birds. A House Wren discovered and used our little house. Afterward, the squirrels started to enlarge the opening, so we bought a large metal washer to go around the opening. Cavity-nesting birds love birdhouses.

4. Make your garden bird-friendly. The British call it a garden, not a yard, which I like. The Audubon Society has lots of suggestions for plants that are good for birds. There are three things you can do to make your garden better for them. First, plant native plants. Find out what works in your area, plant appropriately for sun or shade, and remember to leave the dead stems standing, since there will be many insects, including beneficial bees, hibernating in them. Plant native trees also, a mix of deciduous and evergreen. Second, have a water feature. We have a small pond, but a birdbath works too. Be sure there is a way out of the water for toads or other animals. Even a wet puddle is better than nothing. It is best if the water feature has a drip, though our pond is still. Third, have a brushy area for birds to shelter. Easiest is to pile trimmed twigs and stems in a corner rather than compost them. This will provide shelter for the birds on the coldest nights. On your balcony you could plant native flowers and put out water. Even a vase or trayful of dead stems might attract some birds.

5. Spend time outdoors or at the window. Home is where we spend most of our time. If a bird does something you have not seen before, it is likely to be at home. We eat on our patio whenever possible. Watch what the birds do. You can record these observations in a bird journal for your home. This will be much richer than only listing the birds you see at home. If you have nesting birds, noting the time of various activities is important and is something you can put in your eBird observations. If you do not have a garden, find one nearby, perhaps in a park, and make it a practice to visit, not to simply walk through but to sit awhile.

6. Invite others to see your natural garden. Once you have improved your garden or balcony to be more inviting to birds, use it as a teaching moment. Invite others to see what you have done. Inspire others to expand their own natural environments to make their gardens better for birds, bees, and other insects and wildlife.

Copyright © 2022 by Joan E. Strassmann. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.