PrologueThey came from the sky. And with their arrival went any chance of peace.

It had been shaping up to be a Cannes Film Festival like any other. As the sun rose on a sleepy Saturday—May 12, 1990—across the coastal French city there were flickers of activity. The world’s most prestigious celebration of motion pictures was commencing for the forty-third time.

On the Promenade de la Croisette, caked in chalk-white makeup, an Andy Warhol impersonator was enjoying his fifteen minutes of fame. Cineastes who had been lucky enough to attend the opening gala, a screening of Dreams, the latest by Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa, debated its themes and discussed the surprising cameo by Martin Scorsese as Vincent van Gogh. Others looked forward to the gems of thought-provoking cinema to come, such as Sergei Solovyov’s Russian comedy Black Rose Is an Emblem of Sorrow, Red Rose Is an Emblem of Love.

It was a mecca for those who liked their films dense in subtext and their cafés allongés scalding hot. Notes would be taken. Applause would be meted out. The human condition would be considered.

Then, with a roar, the jet touched down.

It was a chartered luxury 747 out of Los Angeles, a hulking tube of metal polished to a high gleam. It had traveled a little over six thousand miles to its destination. And it was stuffed with an astonishing array of American power players—stars, directors, executives—few of them renowned for making art-house fare.

“The Hollywood of 1990 is on the frickin’ plane,” recalls James Cameron, who had been the last to board in California, having scrambled to finish typing up his first draft of Terminator 2: Judgment Day. “When I got to the airport, they all gave me a snarky clap for being late.”

“It was an amazing flight, a magic trip,” says Renny Harlin, the director who had just blown up two airplanes and half an airport for the yet-to-be-released Die Hard 2, but who hadn’t been banned from high-altitude travel. “There was no shortage of caviar and champagne and that kind of thing.”

More potent refreshments were apparently available, too. “We stopped in Maine to refuel, and after we’d been flying for another twenty minutes somebody gets on the speaker and says, ‘We are now outside of American airspace,’ ” remembers Steven de Souza, writer of the original Die Hard and Commando. “And all of a sudden the drugs come out. People are doing cocaine on the drop-down trays. Then I get tapped on the shoulder and it’s Michael Douglas passing me a joint.”

If Douglas was literally riding high, he was also doing it figuratively, with Wall Street and Fatal Attraction recent hits in his rearview mirror. But the biggest dogs on board were two movie stars whom few would have expected to share oxygen for over ten hours. Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, after more than a decade of bitter warfare, had finally been convinced to appear in public together. The event: a huge party to celebrate Carolco Pictures, the bankroller of many of the bombastic action movies that had ruled the box office for the past decade.

At the airport in Cannes, the disembarking VIPs were each handed an envelope containing 2,000 French francs, spending money for the weekend. Then they were led to a convoy of waiting black Mercedes-Benzes and drivers, at their disposal for the next three days. The vehicles, blue and red lights flashing on their tops, roared down the coast to the decadent Hotel du Cap-Eden-Roc. There, a $1 million soiree—the most expensive ever thrown in the history of Cannes—awaited. One of the world’s hottest bands, the Gipsy Kings, flown in on a separate jet from Spain, performed songs at high volume. And 240 guests joined those from the plane to mill around a massive terrace overlooking the sea, including Mick Jagger (who ended up dancing on top of a table next to girlfriend Jerry Hall), Jean-Claude Van Damme, Dolph Lundgren, Sharon Stone, and Clint Eastwood, who happened to be staying in the hotel and thought he’d check out what all the noise was about.

As the sun went down and fresh seafood was served, the party’s grandest flex was deployed. Rockets blasted up into the Cannes sky, spelling out the names of Carolco’s upcoming projects and the people attached to them. “This firework display said ‘TERMINATOR 2’ in gigantic letters out over the Croisette,” remembers a still-impressed Cameron.

It was a day nobody who attended will ever forget, a showcase of pure excess. Not to mention a cacophony that probably sent Cannes’s more sober visitors—who until that moment had been mulling over the ins and outs of Russian comedy—running back to their lodgings. “It’s the best party ever done,” brags Carolco co-founder Mario Kassar, who put it together. “Everybody was at that party and probably nobody could have done it again.”

There was just one moment of panic along the way. The evening’s coup de grâce had been devised by Kassar: a moment of showmanship to rival even magical fireworks, and which demanded equally careful handling. Schwarzenegger and Stallone, the two titans of action cinema, whose work had brought in millions upon millions of dollars and who were now living, breathing icons, would make a dramatic entrance midway through the event. They had never been convinced to star in a movie together, but tonight they would share a terrace. It would be Carolco’s greatest PR stunt yet, a détente to rival any feat of international diplomacy. Except neither Stallone nor Schwarzenegger would concede on a key point: which of them would enter the party first. That old rivalry, pacified for a while, had suddenly flared back up.

“They were waiting outside, and everyone was asking the question ‘Who’s coming in first, who’s coming in second?’ ” Kassar remembers. A chill swept through the gaggle of Carolco party-planners. After so much expense, could a clash of egos make it all fall apart? Anybody aware of the history between the two stars knew it was a distinct possibility. So Kassar moved fast.

“I took some photos with them—one on the left, the other on the right,” he says, “and they held my hands up in the air. Then I said, ‘Okay, let’s go in now!’ And I came in with both of them. So that resolved that problem.”

Inside the party now, Schwarzenegger, wearing a green-and-yellow Hawaiian shirt, appraised the dance floor like a Terminator scanning a biker bar. Stallone, in a button-up shirt, blazer, and designer sunglasses, did the same. And then, to the amazement of all, the pair turned to each other, locked hands, and started to dance, waltzing in circles around the terrace.

The famous faces in the crowd looked on, delighted. They were present for a monumental moment, a long-awaited truce, two colossal egos finally aligning in perfect harmony.

Then, abruptly, Stallone grimaced and stopped.

“Goddammit,” he told Schwarzenegger. “You’re leading. I hate that.”

America in the 1970s was crying out for a hero. In the last year of the previous decade, the nation had conquered the moon. But now things had gone awry. Abroad, a cataclysmic defeat in Vietnam had dented national pride. At home, the president was being indicted and swarmed by protesters, some wielding signs in which the x in “Nixon” was replaced by a swastika. The economy, which had boomed in the wake of World War II, was wilting, the stock market plummeting 40 percent in an eighteen-month period and joblessness rampant. Everywhere was a newfound sense of despair, felt so keenly and widely that in 1979 President Jimmy Carter addressed it in a speech. “It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will,” he declared with a stony face. “We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives, and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.”

Heroes were in short supply, not least on the big screen. Clint Eastwood’s “Dirty” Harry Callahan thrilled the masses, but returns were diminishing (third sequel Sudden Impact would feature a farting bulldog named Meathead). Gene Hackman’s violent, wild-eyed Popeye Doyle in The French Connection, another lawman, was was intentionally tough to root for. Hong Kong martial arts icon Bruce Lee emerged as a brief, blazing light but died tragically on the cusp of mainstream American success, just a month before Enter the Dragon’s Hollywood premiere. As for the blaxploitation wave, the Richard Roundtree–starring Shaft had made $13 million from a $500,000 budget and inspired dozens of films throughout the 1970s, featuring charismatic actors from Pam Grier to Jim Brown. But while the subgenre had a huge impact, even inspiring the James Bond film Live and Let Die, by the late 1970s it was fading away.

As any fan of action cinema knows, though, it’s when things are bleakest, when all hope is lost, when the villains are smirking and innocent civilians are on their knees, that fresh footsteps are heard, hailing the arrival of a savior. Or, in this case, eight of them.

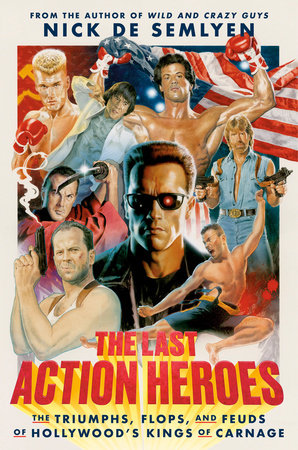

Copyright © 2023 by Nick de Semlyen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.